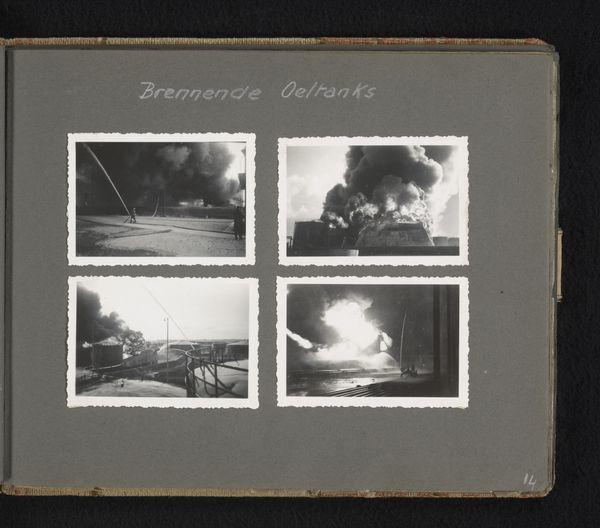

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 63 mm, width 85 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

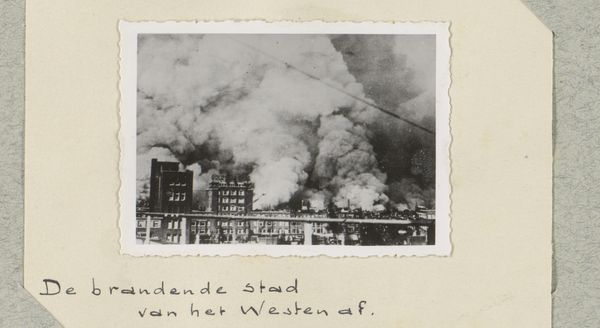

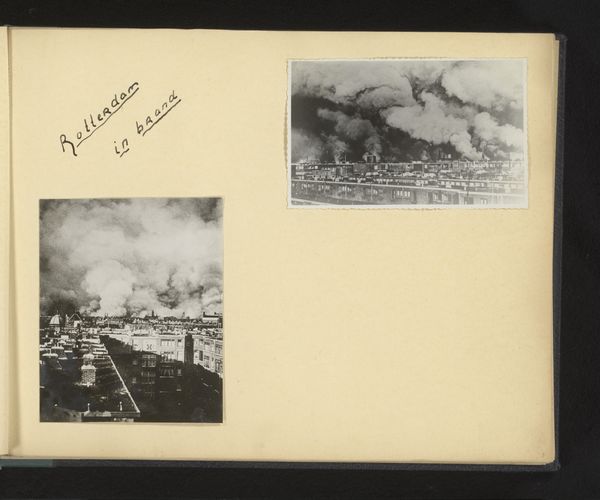

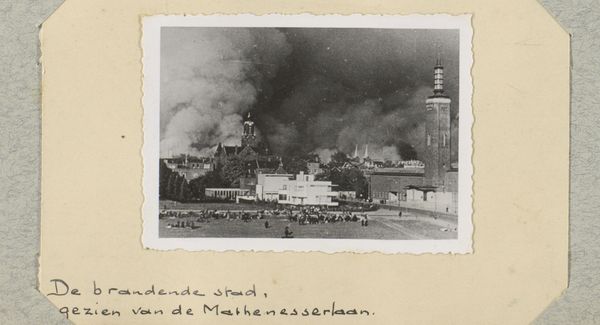

Curator: This gelatin silver print, dating from approximately 1940 to 1945, is titled "Brand en rookwolken bij de Beukelsdijk," which translates to "Fire and Clouds of Smoke at the Beukelsdijk." Editor: My first impression? A powerful visual metaphor. The stark contrast, the dominance of the smoke... it speaks volumes about destruction and upheaval. Curator: Indeed. As a photograph, particularly a gelatin silver print, it allows us to consider the artist J. Nolte’s role as both observer and documentarian during wartime. The technical process itself, the careful developing and printing, suggests a desire to record with precision, even amidst chaos. What materials were available, how long did development take with the resources at hand? The social implications of simply recording an event like this speak to a need for a certain sense of agency during such tumultuous periods. Editor: For me, the billowing smoke transcends the specific event. It’s become a symbol of the broader devastation and perhaps even a representation of repressed emotions rising to the surface. The wispy texture gives it an almost ghostly quality, hovering above the houses as an omen of what may come next. Curator: Interesting, because for me, it also leads me to wonder if there was any work made about this location AFTER it was destroyed. Was there a sense of material, as well as symbolic renewal and regeneration in this area, particularly among working-class populations? Was art used to examine rebuilding and the materials used? I’m deeply interested in what images emerged later to describe changes to daily lives. Editor: I wonder too, looking at it through an iconographic lens, about the symbolism of fire across cultures. Renewal, purification... but in this context, decidedly destructive. Fire often carries those connotations of a transformative power – a necessary step toward rebirth but deeply unsettling in this immediate depiction. The smoke, in turn, veils and obscures, creating an uncertainty about what’s actually beneath it all. It's very unsettling in that way, the houses, in stark relief but about to be taken. Curator: Yes, the artist here chose to use materials that gave a sense of foreboding to a local scene—I wonder what sort of personal relationships he might have had with the Beukelsdijk, and his role as an image-maker in relationship to the location shown? Did he share common work or material relations in general, as was part of the social and economic class of those pictured here? It definitely gives one a sense that class solidarity would be deeply at stake within such destruction and destruction and social upset. Editor: Reflecting on this, the power of a single image, rendered in black and white no less, to condense historical moment, emotional resonance, and symbolic weight, continues to move me. Curator: Indeed. By considering its making and its implications in daily work life, this photorealistic documentation invites complex considerations regarding the social reality of these places that, for working-class subjects, held an extremely meaningful space in their existence and production cycles.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.