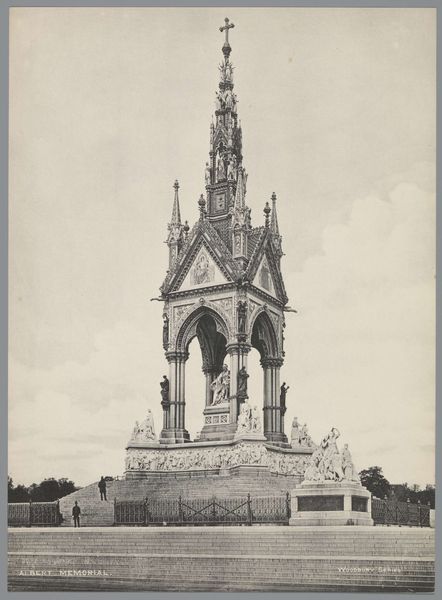

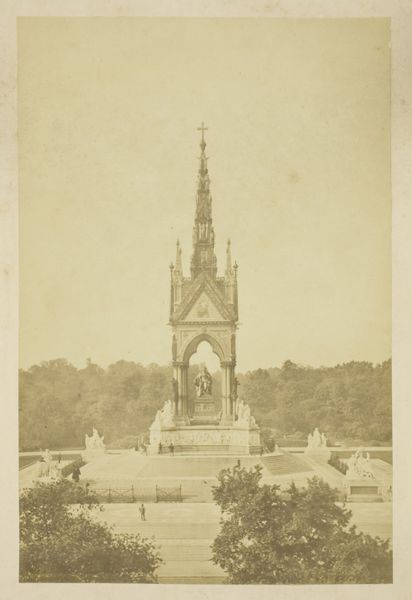

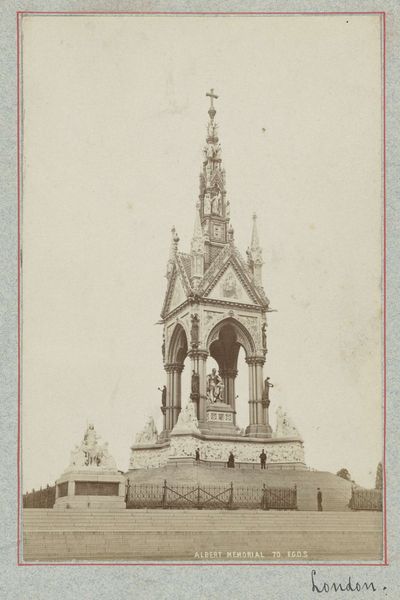

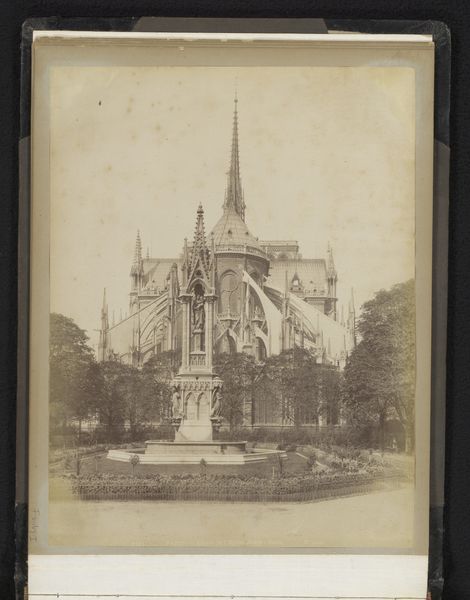

Monument voor koning Leopold I van België in Brussel, België 1884 - 1914

0:00

0:00

gustavehermans

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 281 mm, width 218 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Well, here we have a print titled "Monument voor koning Leopold I van België in Brussel, België." It's attributed to Gustave Hermans and thought to have been made sometime between 1884 and 1914. Editor: It strikes me as an exercise in aspiration, really. It yearns for the heavens but is firmly rooted in... stone, I suppose? A kind of frozen reaching. Curator: Indeed. The image is a photograph depicting the monument to King Leopold I in Brussels. Hermans captured not just a likeness but a statement, I think, about power and legacy through architecture. And we're seeing it here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Look at all the ornamentation. It feels almost aggressively decorative. Each spire seems meticulously crafted, each arch painstakingly rendered, I find myself pondering the labor—the sheer man-hours—involved in bringing such a grandiose vision to life. The workers who quarried and carved the stone, the teams who raised each piece. Curator: Absolutely. One must consider the materials—the specific type of stone used, where it was sourced—and how they reflect on the ambitions and the means of the Belgian monarchy at the time. And look, even the very act of photographing it. Why this particular vantage point? Is it meant to highlight the monument's imposing nature? Editor: I imagine this was a powerful message. Neoclassical architecture like this was often commissioned as a sort of visual language of authority, mimicking ancient empires to legitimize contemporary power structures. Who paid for it? How were they positioned politically? Also, photography as a medium. Was photography considered to be just mechanical reproduction or something that could embody truth and therefore credibility for Leopold’s image? Curator: These photographs were used to portray authority at its height, which made them widely available at the time. So it functioned both as art and documentation for Leopold's legacy. But also how accessible were these images? How were they received? Editor: In the end, examining these things enriches our understanding, beyond just the artistic merit to engage with what that monument physically embodies: Power, history, and yes, human labor. Curator: I'll be considering that intricate interplay of artistry, social message and sheer material effort much longer than just our little conversation!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.