#

quirky sketch

#

pen sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

initial sketch

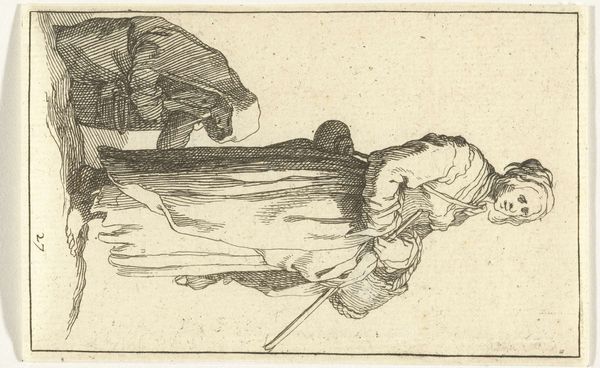

Dimensions: height 130 mm, width 80 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Frederick Bloemaert’s "Jonge boer," created after 1635 and residing here at the Rijksmuseum, immediately strikes me with its directness. What is your initial feeling looking at it? Editor: Exhaustion. Not just the figure seems tired, but also...there’s a fatigue in the very ink. You know that feeling when you’ve been sketching for hours? It’s like the drawing itself needs a rest. Curator: I see what you mean! The rough sketch lines certainly communicate a sense of labor, both of the figure and the artist, but let's consider this sketch in the context of Bloemaert's time. Prints and drawings like this would have circulated widely, impacting representations of peasant life in popular culture. The labor of art-making is, here, deeply intertwined with social depictions of manual labor. Editor: Absolutely. And the pen and ink! It gives a wonderful sense of immediacy. He probably wasn’t aiming for "high art", just capturing a fleeting moment. It's raw, almost like eavesdropping on the artist's thought process. You can practically smell the earthy tones even though it is a monochrome. It feels… honest. Curator: Exactly! Bloemaert’s choices--the materials, the technique, and subject matter-- challenge conventional artistic hierarchies. This isn't idealized pastoral imagery; it's a depiction rooted in the reality of rural toil and craft. Think about the market for prints like these and who had access to them. That access shaped views and perceptions of agrarian societies. Editor: And what’s in the bag! Is it food, supplies...secrets?! It almost feels burdensome, a weight the young farmer carries both literally and perhaps figuratively. It reminds me of the invisible loads we all carry around. And that staff or pole—is it for balance, for support, or just another thing he has to lug around? Curator: Perhaps it's symbolic. The pole provides the figure the balance and protection needed in agricultural labor. Bloemaert presents the work not as a symbol, but in all the social textures of what labor looks and feels like. This provides perspective on access, circulation, and consumption patterns of the day. Editor: Looking closer, it reminds me to be grateful. Not just for the simple things, but for the hands that work, unseen, to provide. And maybe that's what the drawing wants to teach the world - or remind the world- too. Curator: A powerful point indeed, and a potent testament to art’s ability to prompt reflection across centuries. Editor: Indeed. Let’s take that thought with us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.