drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain

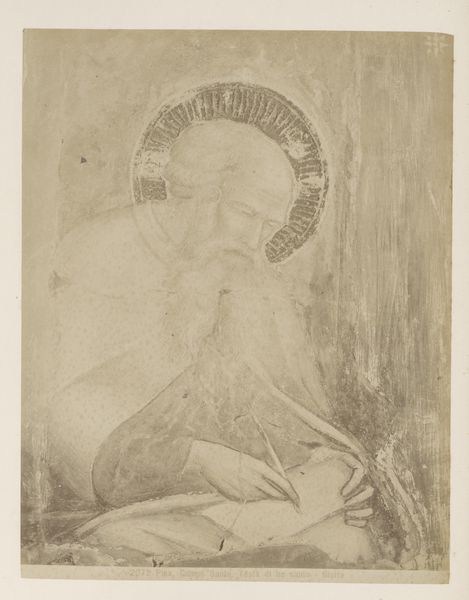

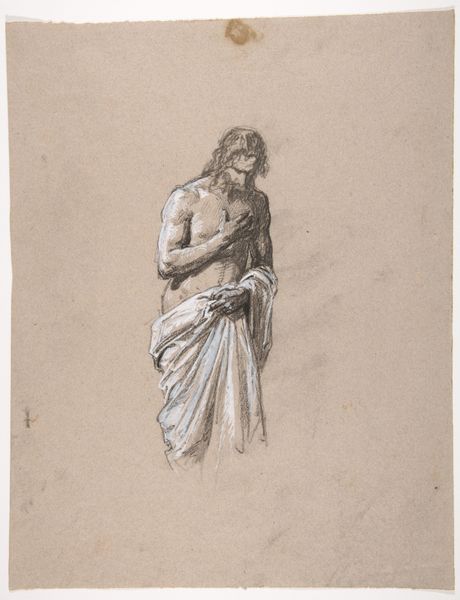

Curator: Before us hangs Philipp Veit's “Johannes der Täufer als Halbfigur mit dem Unterarm Christi,” dating back to 1835 and residing here at the Städel Museum. It captures John the Baptist with a distinctive and reverent posture. Editor: My first thought? The incredible delicacy. It’s a drawing, clearly, and the fine pencil work gives it this ethereal, almost dreamlike quality. The hatching is remarkably executed throughout, bringing the piece to life with the stark shadows cast along his face and the cloth draped across his shoulder. Curator: It's intriguing how Veit, within the Romantic movement, uses the historical figure of John to negotiate the era's shifting religious and political landscape. Think about the sociopolitical debates surrounding faith, secularism, and national identity at the time. This representation is deeply engaged with that discourse. Editor: And considering that it’s a drawing—likely a study for something larger—you really see the artist's hand, quite literally. The crosshatching, the blending... you can feel the labor and decision-making in every stroke. It invites a discussion on the role of craft and how this sketch could stand as a finished work. I imagine Veit standing over a table carefully mapping the subtle lines of John’s hand and brow. Curator: Absolutely. We can consider how such preparatory studies like these gain value over time, as stand-alone artworks. This detailed representation humanizes the saint, but it's also contributing to a much broader narrative of faith and nation-building in the visual arts of the time. It raises the interesting questions about how and why this image was popularized and promoted during a transformative period for German national identity. Editor: The materiality is fascinating, especially how the pencil on paper evokes a certain humility and fragility, contrasting with the traditionally imposing depictions of religious figures. It encourages reflection on accessibility—on the value of readily available materials in portraying subjects historically reserved for monumental paintings or sculptures crafted from expensive and precious material. It begs us to reflect on the role and value of humble processes in art making, elevating "craft" to something more in the traditional understanding. Curator: I’ve always found how Veit connects the viewer with the figure compelling, how the imagery operates as an anchor in discussions about religious art within the museum context. Editor: It offers a lot to contemplate – a reminder of the dialogue between material, labor, and the grand narratives they become a part of. The beauty and simplicity lie within these elements.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.