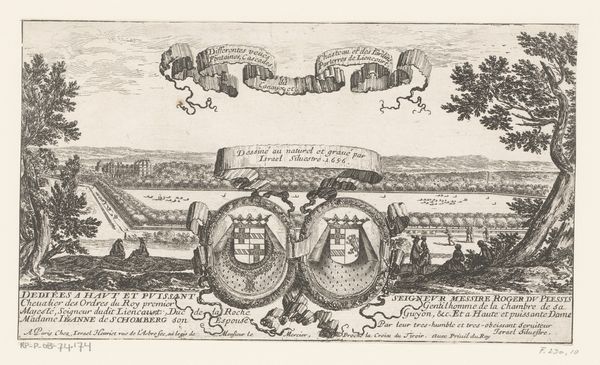

print, engraving

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 108 mm, width 175 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

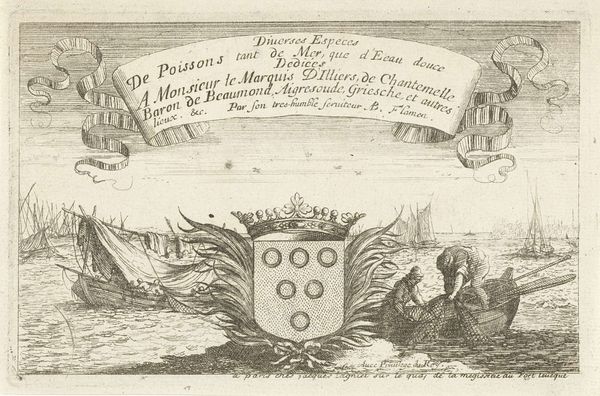

Curator: Let’s consider Albert Flamen's "Zeegezicht door ornamentaal wapen," an engraving likely produced between 1687 and 1749. We see the image’s title within an ornate, decorative frame against a detailed seascape. Editor: Yes, it’s an engraving, a print – it's interesting how this image uses a kind of ‘window’ of ornament to frame a scene of labour at sea. It feels almost… propagandistic, or at least celebratory, of the sea's bounty and perhaps of those who harvest it. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Exactly! Look closer at the inscription— "A Messire Guillaume Tronson…Conseiller du Roy…" The print isn't merely decorative. It's about power, patronage, and production. Engraving itself is a laborious, reproductive technology, and this print showcases that labour in service to royal authority. We need to think about the process. Editor: I hadn’t really considered that the dedication itself becomes part of the material meaning, but it does change how I see the seascape element. Curator: Right! It's the intersection of manual skill and socio-economic structures that interests me. Who were the engravers, the printers, the patrons involved? The quality of line, the type of ink, paper: these speak to the standards, consumption habits, and the overall materiality of art in the period. Where does "high art" stop, and where does "craft" begin when we analyze prints like these? Editor: So, instead of just looking at the scene depicted, we're really looking at how the image itself came into being and its role within a larger network of people and materials? I will definitely look at other artworks this way. Curator: Precisely. It reframes our understanding of artistic value, wouldn't you agree? It becomes about the how and the why, not just the what.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.