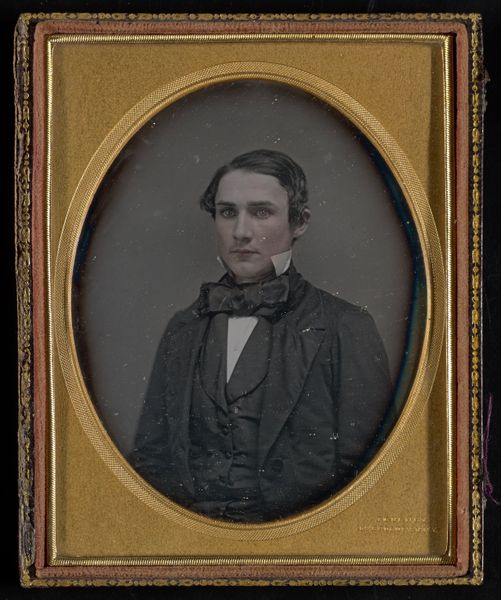

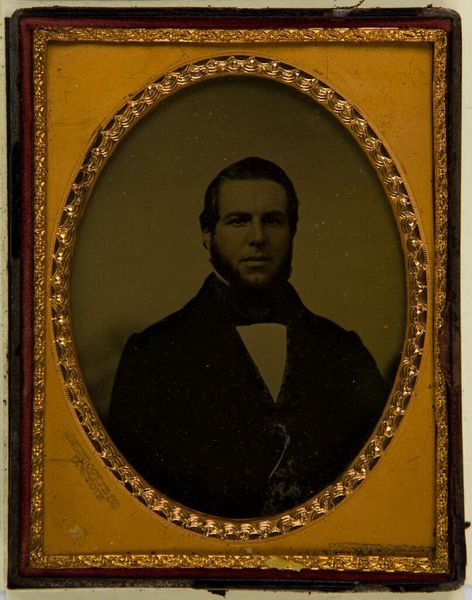

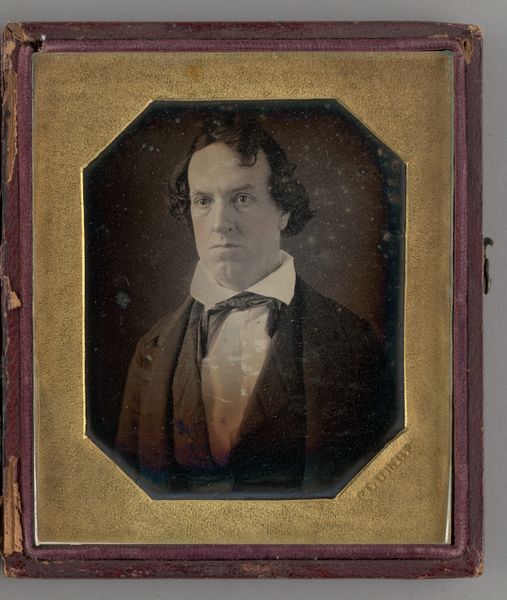

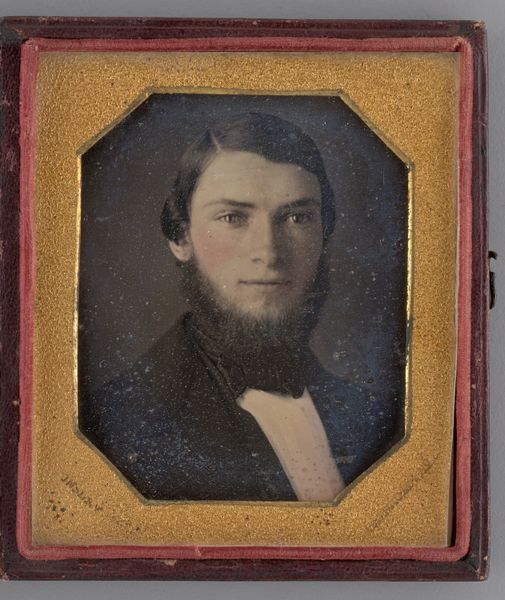

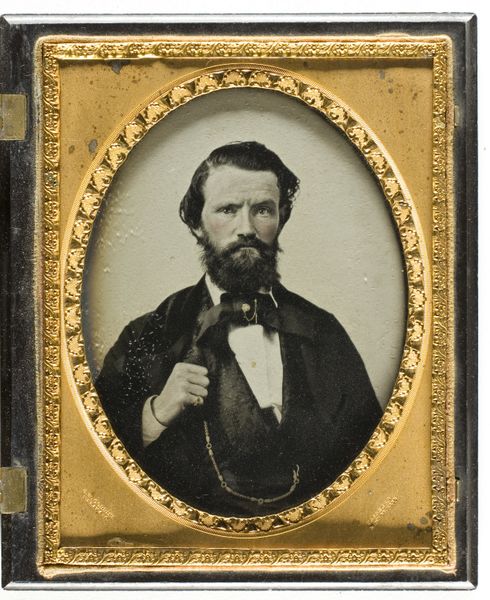

Dimensions: 14.1 × 11 cm (5 1/2 × 4 1/4 in., plate); 15.2 × 24.4 × 1 cm (open case); 15.2 × 12.2 × 2 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

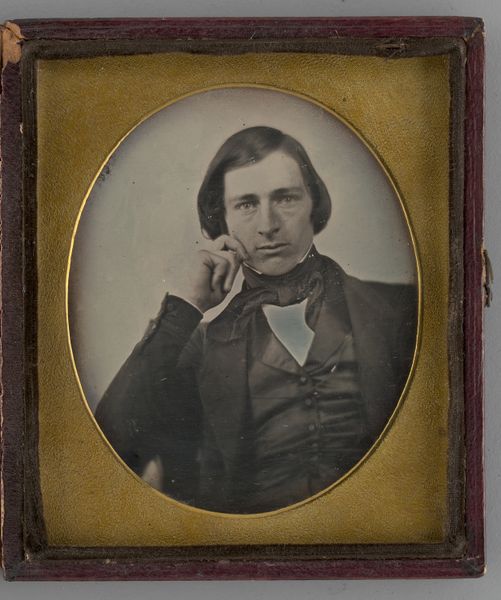

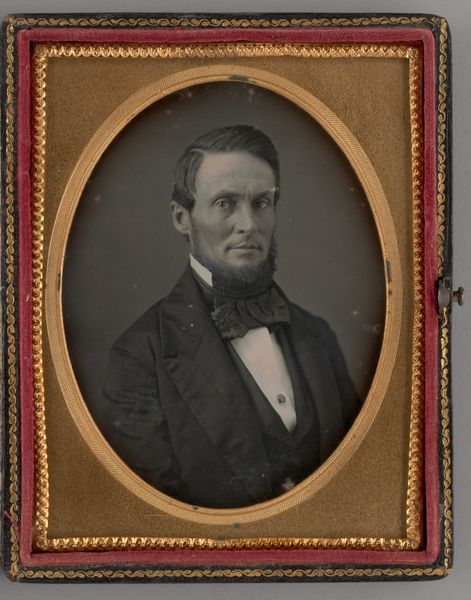

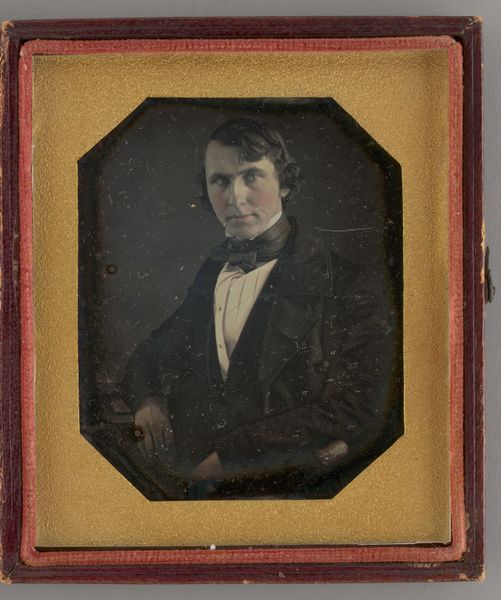

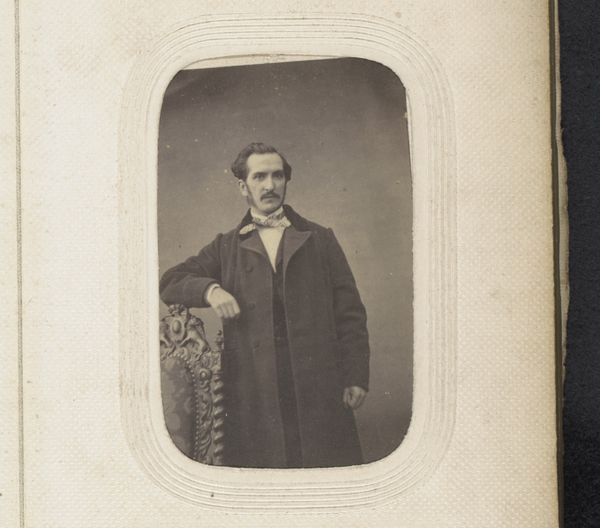

Curator: We’re looking at an arresting daguerreotype, "Untitled (Portrait of a Man)", created anonymously around 1855. It’s currently held here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It's striking, isn't it? There’s an intensity in his gaze, a certain... melancholic air. I’m also noticing the textural elements; there’s a real feeling of tangible substance to it, especially in his dark coat. Curator: Absolutely. The tonal range achieved in early photography is something to behold. Observe how light models the face—a clear emphasis on chiaroscuro contributes to the depth of character. His expression and pose, resting his chin thoughtfully, position the subject as someone of contemplation and intellect. Editor: I'm curious about the process, really. Creating a daguerreotype involved meticulously coating a silvered copper plate, sensitizing it to light with iodine fumes, then developing the image with mercury vapor. Imagine the labor and chemical knowledge that went into making this single image in 1855. Curator: An excellent point. Though often positioned as a straightforward reproduction, early photography was intensely material and mediated. The aesthetic of a daguerreotype owes just as much to chemical processes as it does to artistic intent. The limited dynamic range and heightened contrast produce the dream-like Romantic qualities in such works. Editor: Consider also the social context; the democratization of portraiture that this offered. Suddenly, a likeness was attainable for a far broader section of society than painted portraits had ever allowed. Curator: Precisely. Photography impacted conceptions of representation across media, destabilizing the traditional dominance of painting and profoundly reshaping visual culture. Editor: Reflecting on this, I am struck by how much information is captured in this small object, and its endurance. The subject's identity might be lost to history, but his gaze lives on. Curator: Indeed. We might not know the man, but through careful compositional and material reading, we know much about the modes of representation of the era, its impact on portraiture, and the dawn of modern image culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.