photography, gelatin-silver-print, albumen-print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

albumen-print

#

realism

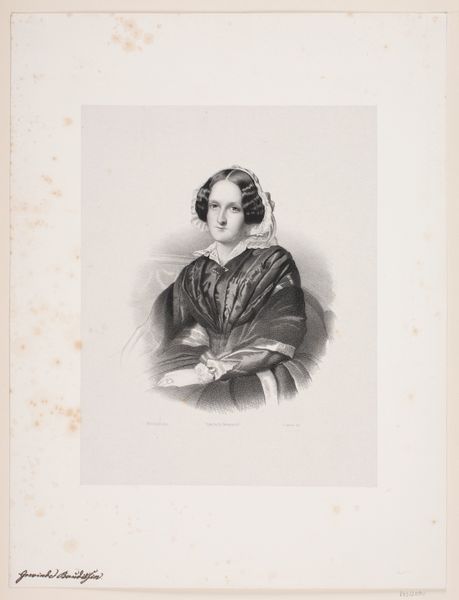

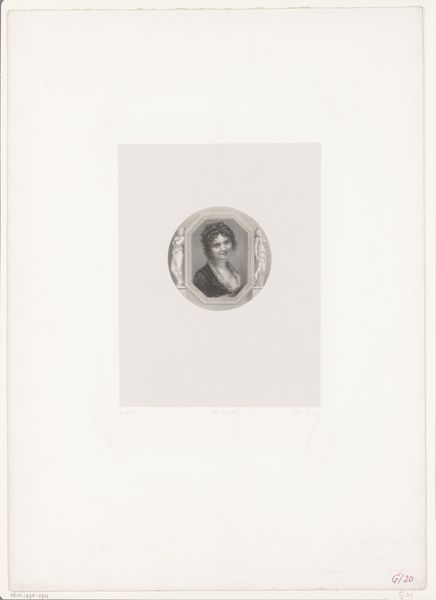

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 101 mm, height 179 mm, width 179 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin-silver print presents a round portrait of Ida van Braam, created sometime between 1900 and 1940 by Stephanus Adrianus Schotel. My first thought? A quiet dignity, almost like a cameo. Editor: The framing, particularly the diamond-shaped mount, certainly elevates her. What strikes me is how much it speaks to constructed femininity during that period. The pearls, the updo, even the almost severe profile – they all coalesce to paint a portrait of idealized womanhood. Curator: Exactly! And the monochrome adds to that timeless feel. It's a carefully curated image, don’t you think? It’s more than just a photograph; it’s a representation. I wonder what story Ida would tell about sitting for it. Did she enjoy the pomp? Did it feel restricting? Editor: It's a powerful question. I feel we are drawn in to ask: how much agency did she really possess in constructing that image, or was she performing within socially imposed boundaries? The tilt of her chin hints at both strength and restraint, doesn’t it? This in-between state seems so compelling. Curator: Absolutely, there is this duality to it all. The sharp lines of the framing clashing a bit with the softer features, giving it that wonderful sense of tension. Maybe it hints at how women navigated public and private spheres? The albumen print creates this dreamlike yet structured atmosphere... Editor: I completely agree. Furthermore, it makes one think about the economic conditions required to produce images of this type in that time period; who was afforded this level of "permanence." As it embodies both privilege and the carefully constructed presentation of self, it raises important questions around social and cultural dynamics. Curator: Well said! Ultimately, looking at it this way brings the past so palpably close; as you implied, it urges us to wonder about lives lived within those frames. Editor: Indeed; beyond its aesthetic allure, it provokes introspection on historical representation. Perhaps there is no “single story” in the picture, after all!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.