drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 360 mm, width 280 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

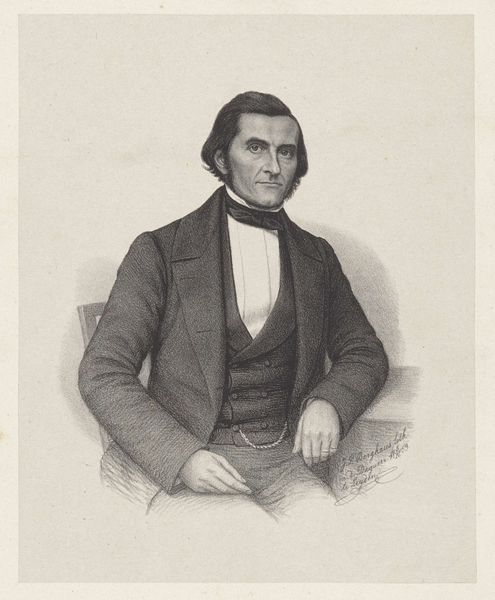

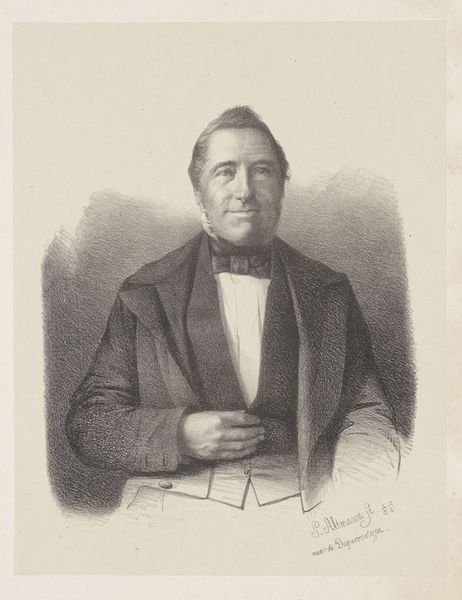

Curator: Standing before us is Leonard de Koningh’s "Portret van H.J. van Gruting," created sometime between 1850 and 1862. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's something quite stoic, almost melancholic, about his gaze. The restrained palette contributes to this rather serious mood. Curator: Indeed. Let’s consider the material reality. De Koningh executed this portrait primarily in pencil. Notice the precision in the hatching, creating volume and texture, from the subject's wool coat to the ornate fabric he rests his hand upon. This kind of detail speaks to the labor involved. Editor: That brings up an interesting point regarding class. This is a portrait of H.J. van Gruting. It would be fruitful to understand more about him: his class position and profession must be tied to representation here. How does the artist subtly affirm or perhaps even question social hierarchies? Curator: Certainly. The materiality points us back to the networks of production—from the graphite mines to the paper mills that sustained this portrait's creation, these details often get elided in more formal art historical considerations. We can view this through the lens of broader economic activities tied to portraiture itself. Editor: It is vital to read images like this as cultural artifacts that participate in identity formation. This subject projects an image of bourgeois respectability, even authority. Consider the racialized history of portraiture—who gets to be seen and remembered? Curator: Precisely. Examining who commissions such works, what materials are chosen, and how labor is manifested deepens our understanding beyond mere aesthetic appreciation. The weave of that fabric isn't just an aesthetic detail; it's a trace of textile production, trade, and consumption patterns within 19th-century Dutch society. Editor: In closing, viewing van Gruting here through De Koningh's pencil yields rich context. This piece makes us mindful of both past narratives, the labor it involves, and it invites a deconstruction of portraiture. Curator: Yes, it reveals the inherent tension between representing individual identity and larger networks of power. Analyzing materiality illuminates its status as more than just fine art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.