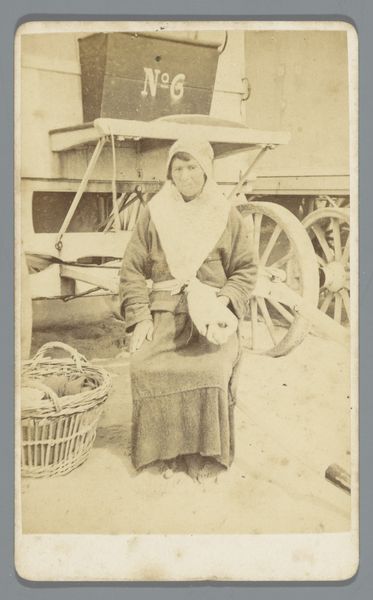

Portret van een onbekende vrouw met juk in klederdracht van Arnemuiden, Zeeland 1860 - 1890

0:00

0:00

andriesjager

Rijksmuseum

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

portrait reference

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 61 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a striking image. This is a daguerreotype, "Portret van een onbekende vrouw met juk in klederdracht van Arnemuiden, Zeeland," created sometime between 1860 and 1890. The photographer is unknown, but the sitter's attire and burdens tell a clear story. Editor: My immediate impression is the weight she carries, both literally and figuratively. There's something deeply compelling in the tension between her stern gaze and the obvious labor demanded of her. It’s unsettling, yet I'm also drawn to her strength. Curator: Absolutely. The composition is carefully arranged, centering the woman. Her traditional dress and the yoke—the 'juk'—emphasize the textures and patterns: polka dots in her top and quilted in the dress. See how they play against the sharp lines of the yoke. The composition speaks to formal balance and photographic clarity. Editor: For me, the 'juk' is loaded with meaning. It's a symbol of the societal pressures placed on women, specifically those of the working class. How did such women experience the intersectionality of class and gender in 19th-century Netherlands? We can analyze her positioning as a kind of subjugated worker in service of…what? Curator: True. However, consider also the technical brilliance. Daguerreotypes are exceptionally detailed and were groundbreaking in their time. Every wrinkle in her clothing, every strand of hair, is captured with astonishing precision. This material reality emphasizes presence over any symbolic interpretation, in my opinion. Editor: Perhaps, but photography at the time was hardly neutral. The image seems self-aware of its performativity as social document. Who produced this? Why did they photograph her? Was this intended as ethnographic documentation or simply to record her servitude for future exploitation? These formal qualities become signifiers of power. Curator: I agree, a reading along those lines provides valuable context to her being. It presents a powerful counter-narrative to dominant cultural displays. Editor: It allows a space to examine the way marginalized figures are presented and framed—perhaps revealing less about her, and more about the person controlling the camera lens and societal pressures prevalent at that time. We are challenged to see what their truth really entails.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.