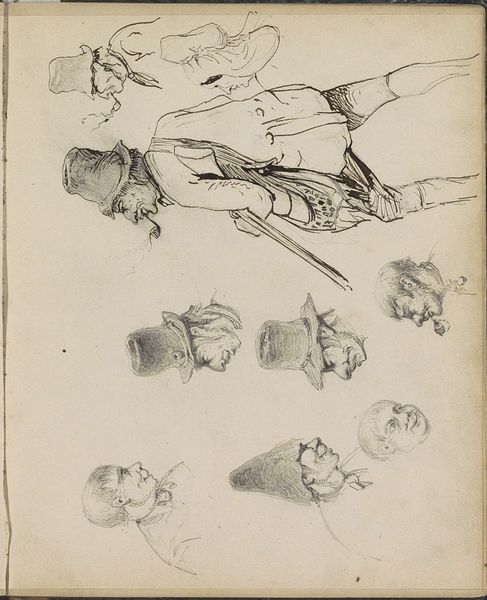

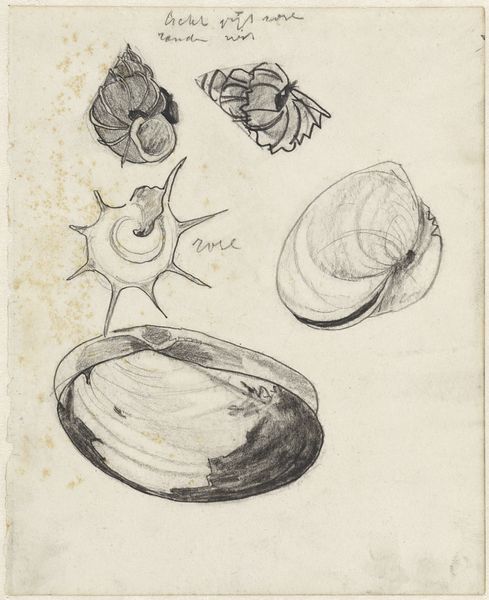

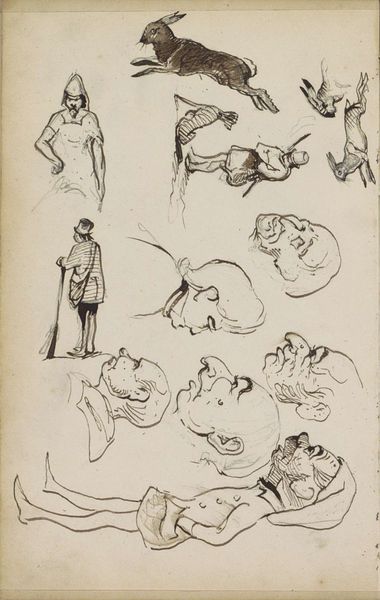

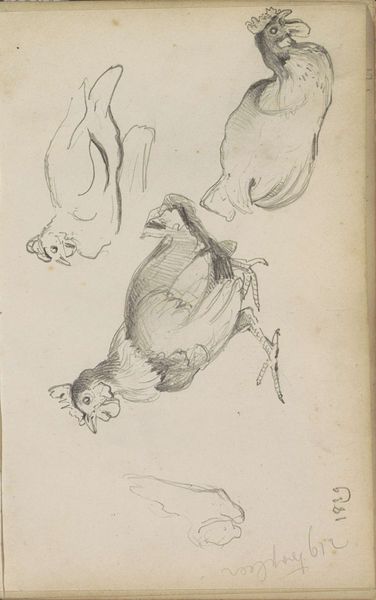

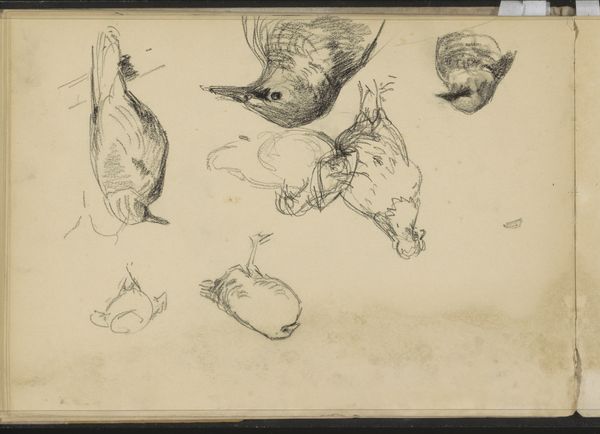

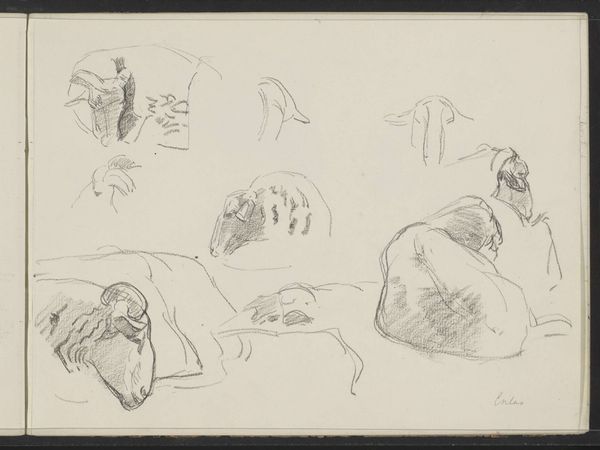

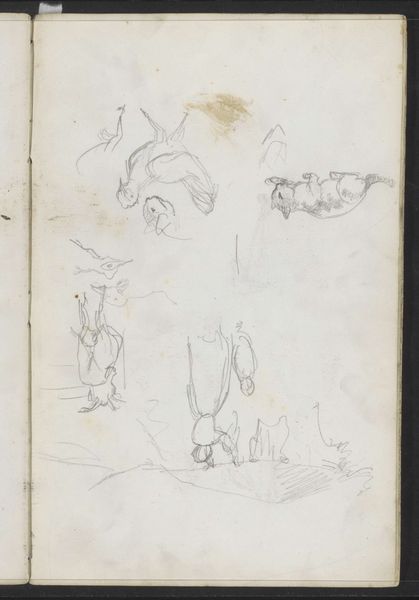

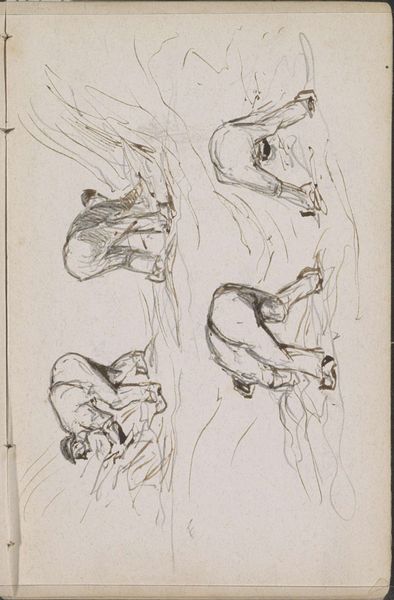

drawing, ink

#

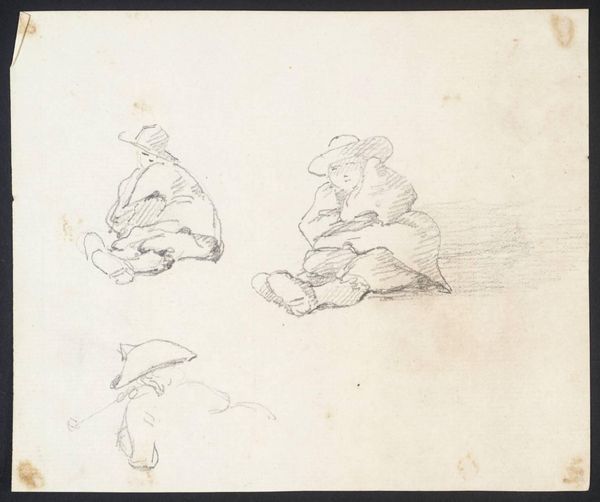

drawing

#

landscape

#

ink

#

folk-art

#

naturalism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

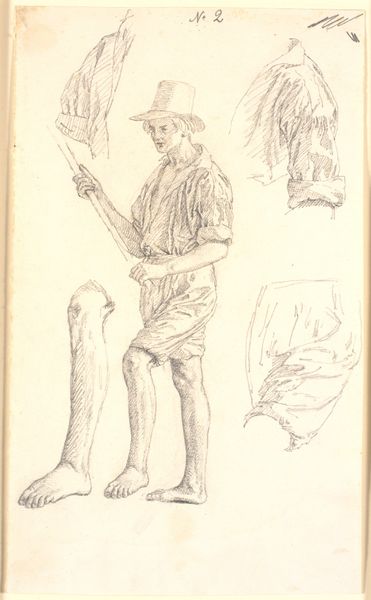

Curator: What a fascinating sketchbook page! This drawing, entitled “Paddenstoelen,” or “Mushrooms” in English, comes to us from Johannes Tavenraat, dating roughly from 1841 to 1853. Note his skillful rendering in ink. Editor: It strikes me as melancholic, a little somber. The washes of ink, the stooped figure… it evokes a certain weariness. Curator: Indeed. Let's think about Tavenraat’s world. He worked during a period of enormous industrial and agricultural change, especially affecting rural labor. Drawings like this allowed careful study and cataloging of nature, turning lived experience into knowledge through drawing techniques. Editor: And isn't there something compelling in how these humble mushrooms, these fungi, are rendered with such care and attention? It subverts a hierarchy; nature typically deemed less worthy becomes central. It makes me think about accessibility, who has the resources to study art and nature. How were drawings like this made available, and to whom? Curator: Absolutely. Consider, too, the material limitations and advantages. Ink allows for delicate lines and textures, suitable for botanical studies intended for scientific circles. But at the same time, inexpensive sketches of this kind served to share these images, making them accessible, through folk-art publications for instance. Editor: This interplay of high and low reminds us that the boundary lines of the art world were constantly negotiated through art. The lone figure adds to my theory; is it a comment on human labor’s relationship with the environment? The environment that literally sustains. Curator: A possibility! We often overlook the sheer physical effort involved in rendering these works—the labor is etched onto the very paper itself through Tavenraat's patient, exacting hand. Editor: These are images that demand we unpack what labour even means, the social relations of artistic production during the era. Curator: It leaves one reflecting on nature's quiet endurance, doesn’t it? Editor: Absolutely, and on our enduring need to interpret it and each other, in context, to make sense of both art, and the world at large.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.