#

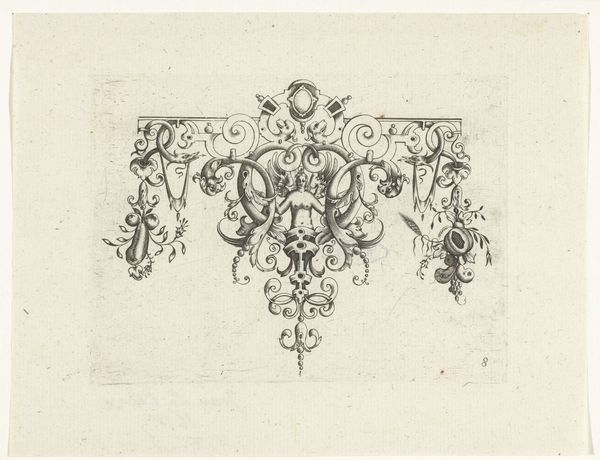

pen drawing

#

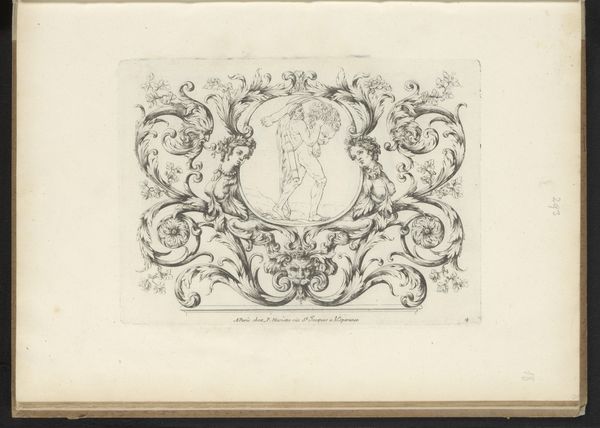

pen illustration

#

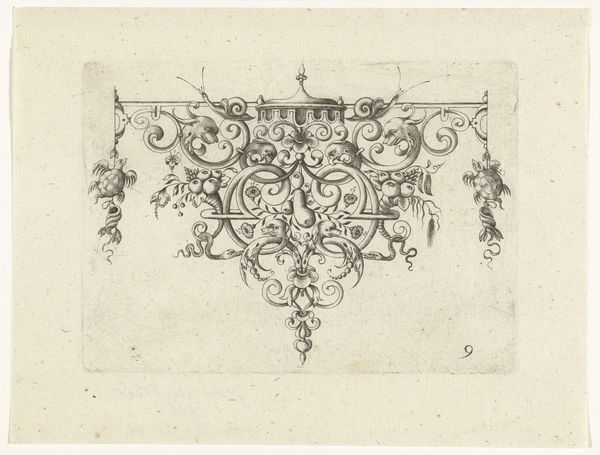

pen sketch

#

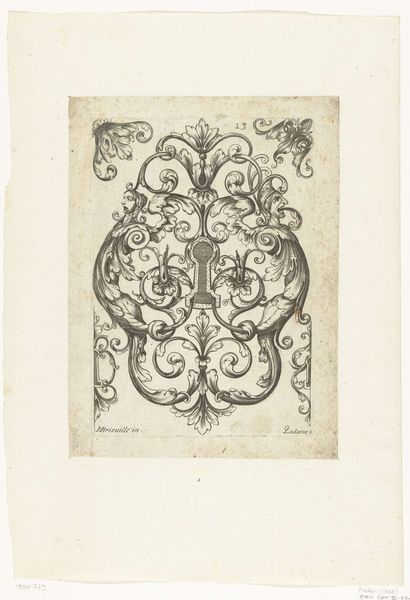

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 108 mm, width 180 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

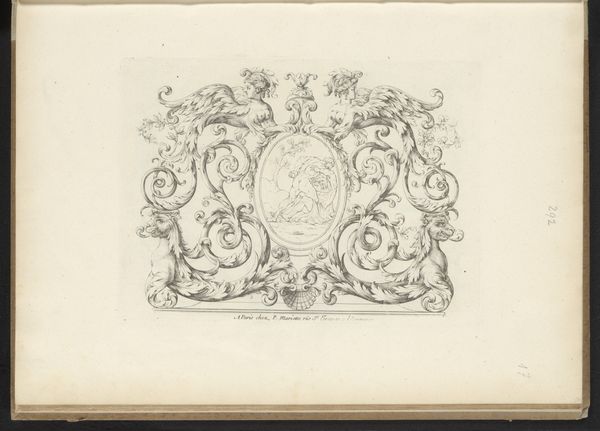

Curator: This delicate drawing before us is titled "Tafelen der wet," or "Tablets of the Law," created by Bernard Picart sometime between 1683 and 1733. It’s a pen drawing currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought is, what intricate detail! The scrollwork alone is mesmerizing. The almost playful quality it adds contrasts strikingly with what I know the content to be: a set of religious commandments. Curator: It's crucial to remember that Picart was working in a period where religious identity was fraught with political tension. This drawing of the tablets of the law, likely intended for dissemination through print, participates in complex dialogues surrounding religious tolerance. Consider, who was his intended audience? And what did rendering these iconic tablets in such a stylized way achieve? Editor: It's a fascinating blend of sacred law and ornamentation. Looking closely, one is struck by the quality of the ink, and the repetitive mark-making needed to create tone. There is so much control of medium on display here; so much labour. The means of reproducing something like this would involve an etcher or engraver whose skill was highly prized. I would be interested to know whether Picart designed it as something intended for further fabrication, or as an art object unto itself? Curator: Your point is well taken. This era saw a democratization of images, as printmaking allowed ideas—religious, philosophical, political—to spread far and wide. Perhaps this stylization made the tablets less intimidating, more accessible to a wider audience navigating religious plurality? Also we need to be sensitive to this piece within a wider artistic culture. The presence of an angel at the top hints to something outside a pure Judaic setting. What does this syncretism say about the culture this came from? Editor: It also encourages one to ask broader questions about value. Here we have what is effectively a 'copy' of something deeply culturally significant – the tablets containing the ten commandments – but rendered as decorative 'art'. Where does the real value lie – with the sacred source object, or with Picart's interpretation and labour? The way he worked with ink becomes meaningful in this consideration. Curator: I think unpacking the image within a broader intersectional context allows us to engage with it meaningfully today. Editor: I agree, understanding the conditions of its production brings so many nuances into view. Thank you for highlighting it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.