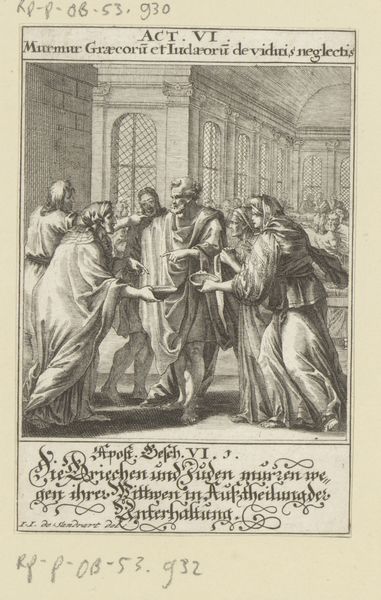

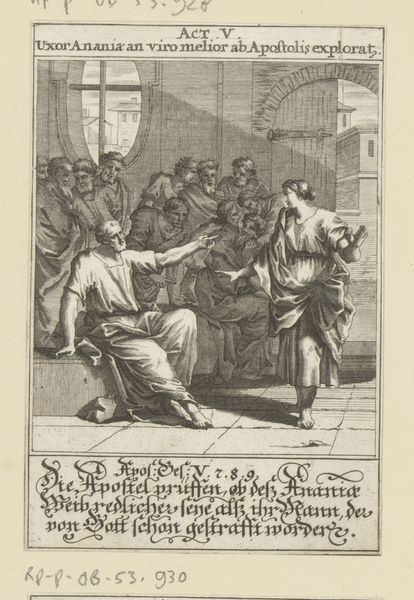

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

group-portraits

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 156 mm, width 102 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, known as "Kerkinterieur met geestelijken" or "Church Interior with Clergy," dates back to 1665. Reinier van Persijn is credited with its creation, and it now resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, the crosshatching that composes it jumps out at me. The figures are caught between the weight of detail and an openness to expression, almost like seeing sketches layered to life. What can you tell me about the historical importance? Curator: Well, historically, we see here an example of Baroque portraiture through the detailed depictions of these figures within a staged setting, most likely intended for broader circulation, thanks to the print medium. These types of depictions carried specific messages regarding religious power and knowledge. Note, too, its production in the Dutch Republic. Editor: Exactly! That production detail provides interesting context—engraving meant multiple copies, a means to rapidly disseminate and circulate both religious imagery and influence in the mid-17th century. I can already imagine that these prints offered the merchant class entry into otherwise unseen scholarly circles. Curator: Precisely. It speaks volumes about accessibility to religious and intellectual life at that time. By the 17th century, the print medium had indeed been refined into an exceptional format. Consider the use of line to convey depth in the figures' robes, as well as shadow; Persijn wielded the form masterfully. Editor: Indeed. And given that this particular print was published in Leiden and Rotterdam, we have to also examine its social position to understand how the publisher made this image readily accessible across major mercantile regions of the Netherlands. But, honestly, that one straggler with his arms crossed does offer levity against an otherwise weighty group portrait. Curator: I completely agree. Ultimately, it serves as an exceptional glimpse into the visual and intellectual world of the Dutch Golden Age and demonstrates how images, even printed ones, played a vital role in shaping religious perception and social standing. Editor: And through considering it with respect to its place of production, we’ve uncovered so much of what a simple engraving reveals. Thanks to its enduring medium, centuries later it's still stimulating fascinating conversations about art and history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.