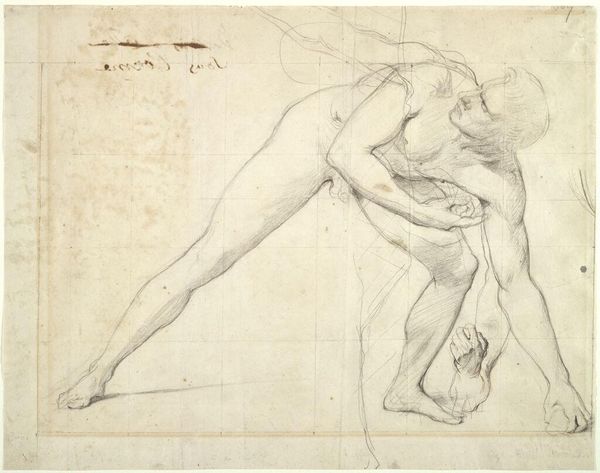

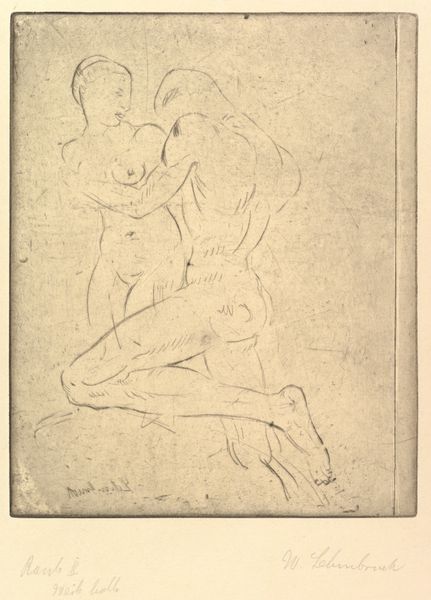

A male nude reclining on his back with his legs turned up, and a study for a pair of turned-up legs seen from behind 1601 - 1661

0:00

0:00

drawing

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

academic-art

#

nude

Dimensions: 249 mm (height) x 361 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: This is "A male nude reclining on his back with his legs turned up, and a study for a pair of turned-up legs seen from behind," a drawing by Francesco Montelatici, created sometime between 1601 and 1661. Editor: The sketch, in what looks like sanguine chalk, creates an intriguing sense of torsion. The body is relaxed, but those legs—splayed, almost defiant, force an unsettling energy into the composition. Curator: Yes, that tension you feel stems from a visual legacy reaching back to classical sculpture, imbued with a distinct academic purpose. Note how the red chalk models form, testing the limits of foreshortening and anatomical understanding, prevalent during the Renaissance. Editor: But what does the reclining figure signify here, and how should we address that classicization and the legacy of nude studies when this period was filled with political turmoil and inequity? The Renaissance was no paradise, and these seemingly neutral studies served to idealize specific, often male, forms. Curator: Consider though, the possible influences. There's the sleeping Eros in Hellenistic sculpture or perhaps a subtle echo of Michelangelo's studies. Montelatici grapples with these precedents and also adds an extra set of legs in the upper-right, as if searching for the perfect expression of the form. Editor: True. This work speaks to an art concerned with mastery of the body in a very literal sense, maybe we also should be attentive about which bodies are valued in this cultural formation. Were female figures also offered such open ended study, or men of different socio-economic statuses and backgrounds? Curator: Perhaps this is meant as a statement of male confidence and potency. The artist seeks an archetypal androgynous being to which the audience can see themself represented through the male model displayed in this image. Editor: In the nude studies we've examined thus far, the subject can be understood to be less about that individual, and rather to exemplify a type of power. Even as the sketch exposes an exercise in an artist's work, it raises profound questions. Curator: Ultimately, this study compels us to look closely at our inherited ways of seeing, not just at art, but also at ourselves. Editor: Precisely. Recognizing that these depictions reflect a long history of power and social codification offers avenues for dialogue. Art then, challenges not only us to engage its immediate visuality, but the visual history as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.