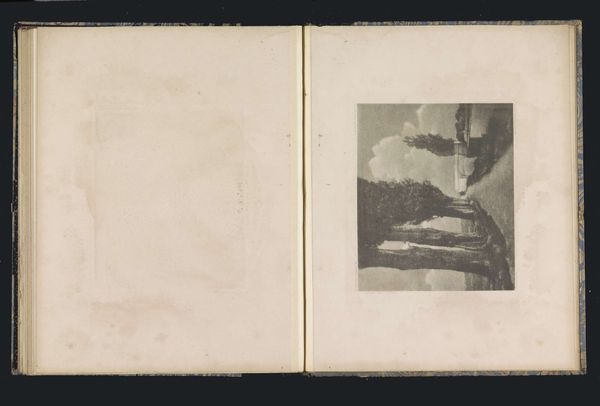

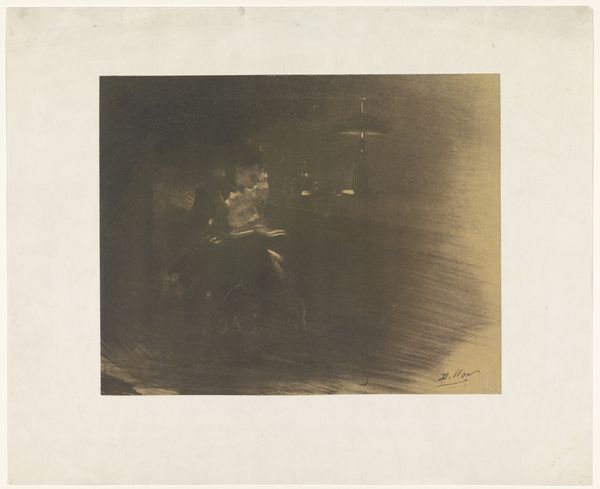

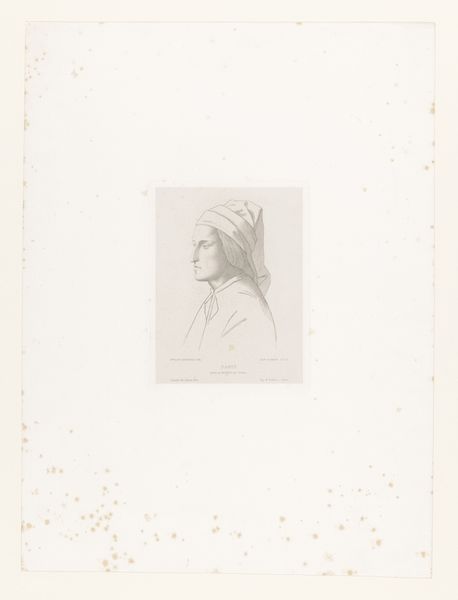

Nicolaas Henneman in the Cloisters at Lacock Abbey 1841

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

Dimensions: Image: 4 1/8 × 4 7/16 in. (10.5 × 11.3 cm) Sheet: 7 5/16 × 8 7/8 in. (18.5 × 22.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: The hazy sepia tones lend a feeling of distant memory to this print. The lighting is so soft, it almost seems to emanate from the figure himself, like an aura. Editor: You’re responding, I think, to William Henry Fox Talbot's "Nicolaas Henneman in the Cloisters at Lacock Abbey," created around 1841. It's considered an early, groundbreaking example of photography, a calotype. Henneman was Talbot’s former valet and later the manager of Talbot’s photographic establishment in Reading. Curator: Fascinating! So, it's like a glimpse into the nascent days of photography. There’s such a painterly quality, so subtle, that one can be reminded of Dutch Golden Age masters, like Rembrandt or Vermeer. Editor: I agree; though photography was new, portraiture was not, so early practitioners drew heavily from painting. More than just aesthetics, the photograph, like a painting, solidified social positions through representation. Henneman isn't just being recorded, he is being elevated, placed into a lineage of respectable men. Curator: Absolutely! The cloisters add such an element of intrigue, and you’re so right, the photograph itself speaks to issues of class and visibility. This cloistered setting is so...evocative. It's a space designed for reflection, now made a stage. He stands confidently with an open jacket; is he hot or just cool? It’s an inside joke. Editor: Note the contrast between the smooth, pristine columns and the rough edges of the print itself, emphasizing the materiality. Early photography demanded long exposure times, rendering stillness and composure vital to the outcome. Here, too, stillness is a virtue linked to both patience and the implied leisure afforded to figures of standing. Curator: I never really thought about that tension. Editor: In art and photography of this period, especially in depicting men, you often see this carefully constructed performance of virtue, control, and social authority. The way Henneman composes himself is part of a very particular language of power. It's subtle but absolutely palpable. Curator: What strikes me most is this image feels somehow incomplete; and not just physically with the unfinished border. Is this because we still have the afterglow of the big bang of photography, the genesis still rippling in what followed after? This ghost in the machine? Editor: Perhaps it's also because every photograph inherently speaks to both presence and absence, what is captured and what is forever gone. This photograph memorializes Henneman, but also an early, hopeful moment in visual culture, where the very act of seeing seemed newly magical.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.