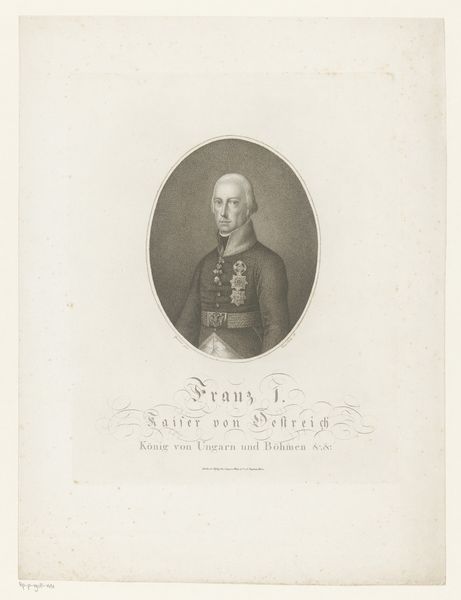

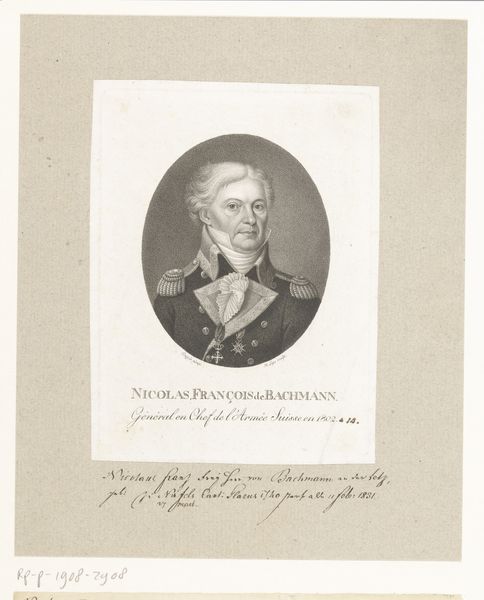

engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

aged paper

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 144 mm, height 96 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

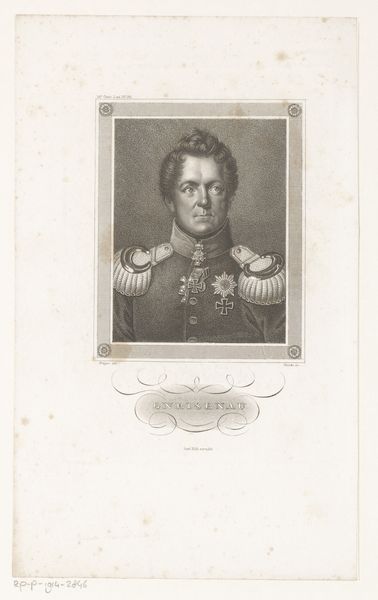

Curator: Immediately, what strikes me is its stillness. Despite all the ornamentation of his attire, he comes across as rather withdrawn. Editor: We're looking at a portrait of Friedrich Franz I, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. The piece, crafted sometime between 1800 and 1830, is an engraving, placing it squarely within the Neoclassical movement and its emphasis on clarity and order. Curator: Yes, the rigidity of the pose is definitely Neoclassical, but there's something…almost weary about him. The symbols of power, the stars and braid, almost weigh him down, suggesting maybe the human cost of maintaining authority. I am curious what part did political imagery and representation play in legitimizing the rule. Editor: Absolutely. These portraits functioned as a very particular kind of propaganda, carefully crafted to project power and stability, the key values championed by ruling elites during times of intense political upheaval and revolution. Every element is carefully considered to contribute to a desired message of leadership, order, and even divinity, given its quasi-religious employment of classical references. Curator: The engraving medium itself plays a part. Its inherent reproducibility means this image, this carefully curated message, could circulate widely, shaping public perception. Who did images like this hope to inspire and how successful were these images at actually communicating the virtues or even deterring disobedience? It's critical to evaluate whose image gets broadcast and by whom in terms of the social, cultural and gender constructs. Editor: These engravings allowed a broader dissemination of aristocratic imagery, influencing not only the common people, but shaping how these figures wished to be perceived and remembered. It reinforced a hierarchy, absolutely, while it established lasting iconographies and conventions in representing power. Curator: Thinking about its cultural and social impact, portraits like these perpetuated and solidified notions about gender and status. The Grand Duke's stoic visage reflects traditional masculinity while visibly solidifying class division in the newly emerging societal structures and power. What, if anything, can it reveal about access? Editor: Perhaps it reveals as much as it conceals about the actual power structures at play in Mecklenburg-Schwerin during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It’s an exercise in controlled projection that offers both insights and raises essential questions about how we construct narratives of leadership through imagery.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.