drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

baroque

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

history-painting

#

sketchbook art

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

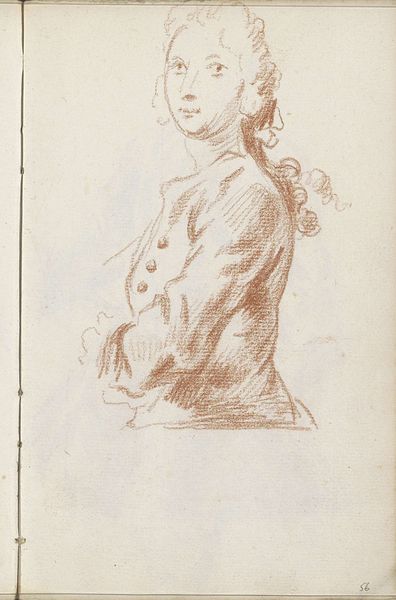

Editor: This is "Standing Man," a drawing made with pencil on toned paper between 1710 and 1772 by Petrus Johannes van Reysschoot. I am immediately drawn to the sitter’s clothes. What does this sketch tell us about status and identity at that time? Curator: This sketch presents a figure embodying the aesthetics of the Baroque era, yet we should look at what's *not* represented, too. Van Reysschoot’s work provides an insight into the visual markers of elite identity of that era - such as powdered wigs, drapery and decorum-related poses. But let’s consider the social forces at play. How might social hierarchies shape who got represented in art, and how? Editor: I see your point. It’s easy to admire the style without thinking about who was excluded from these depictions. It also reminds me of performance; a demonstration of wealth on toned paper that isn't permanent. Curator: Exactly. Who held the power to commission these works? What messages were they trying to send about themselves, their class, their position? Considering portraiture within this historical frame reveals it not just as documentation, but as an active participant in upholding power structures and celebrating inequality. How does that reading affect your perspective? Editor: It complicates things, but in a good way. I definitely need to rethink my initial, more superficial response, which really was all about "nice clothes!". Now it feels like an opening to deeper conversations about representation and power. Curator: Precisely. Engaging with art in this way challenges us to move beyond the aesthetic surface and ask critical questions about history, identity, and social justice, enriching our understanding and challenging conventional narratives. Editor: I agree. Now, looking at the work as a glimpse of how inequality was manufactured is much more interesting. I see much more in it now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.