etching, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

form

#

portrait reference

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

#

realism

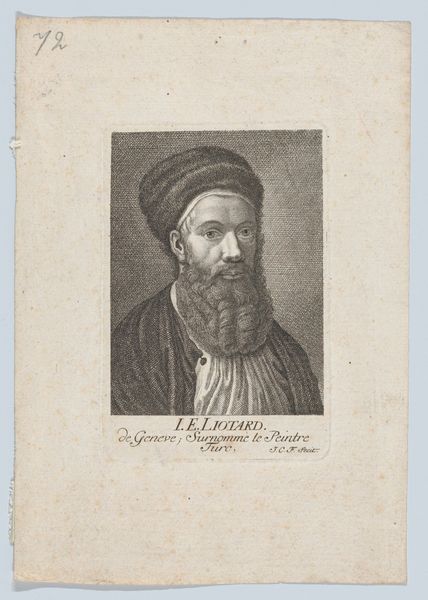

Dimensions: height 139 mm, width 111 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

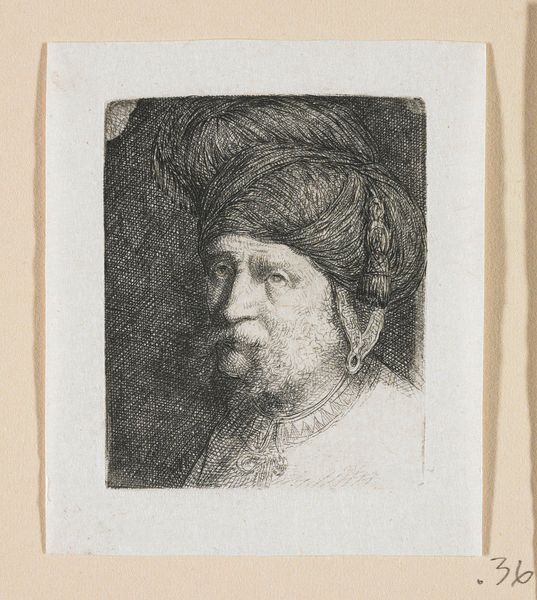

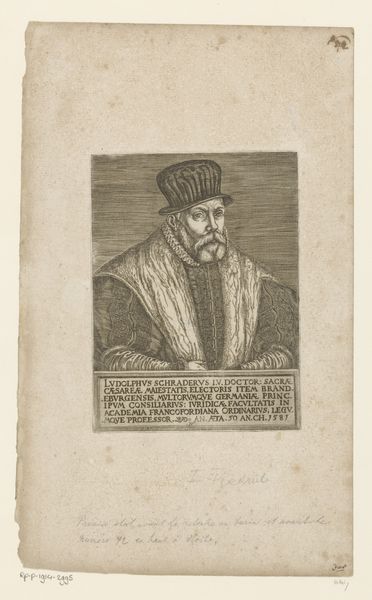

Curator: Look at this engraving, "Head of a Man with a Fur Cap", attributed to Samuel van Hoogstraten and created sometime between 1648 and 1678. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: My first impression is the density of lines. It's remarkable how the artist captures so much detail and texture with just simple lines etched into the plate, and transferred onto this work. The face seems both aged and intensely present. Curator: Absolutely. Think about the role of portraiture during the Dutch Golden Age. It wasn't just about depicting likeness; it was about constructing identity, and solidifying social status. This man, while unnamed, exudes a certain gravitas, doesn't he? The fur cap hints at a certain level of affluence. What statement do you think he's making? Editor: I am drawn to the fur cap itself. It screams material signifier, doesn’t it? Reflecting the thriving trade networks that fuelled the Dutch economy. This particular item was undoubtedly part of the supply chain; where it was acquired, how it was processed, and the labour involved are all very relevant to the production of the work. It’s worth further examination. Curator: That’s a keen observation, about global connections impacting a single etching. Consider too the social hierarchies it reveals. A portrait, like this one, functions as a marker of privilege. Who had access to the artist, to the materials? Who was considered worthy of representation? And, conversely, who was deliberately excluded from the artistic record? Editor: You’re highlighting issues that persist, the portrait as record; there is also the mechanical act. Each individual stroke represents an interaction with the plate. Its labour. A labour designed to meet the demand, maybe. Curator: A powerful point. His expression, too, complicates any straightforward reading of status. There's a weariness, perhaps even vulnerability, that transcends class boundaries. It's a potent reminder of the human condition, and it speaks to questions about emotional representation, class representation and identity in the golden age, and maybe our age, too. Editor: The discussion underscores that portraits carry layers of meanings related to material, class and gender constructs. It helps re-evaluate its purpose. Curator: Indeed, an engagement with social frameworks gives us ways to read a portrait beyond mere likeness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.