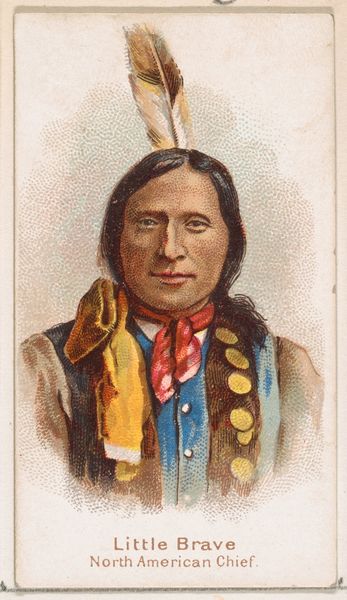

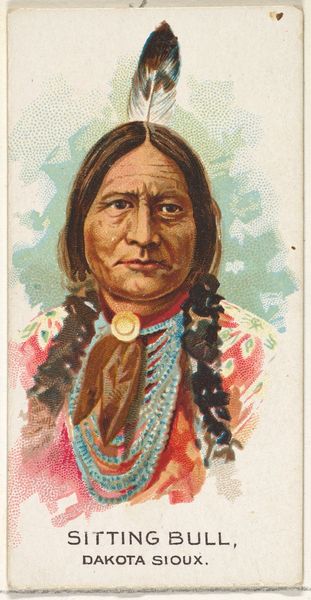

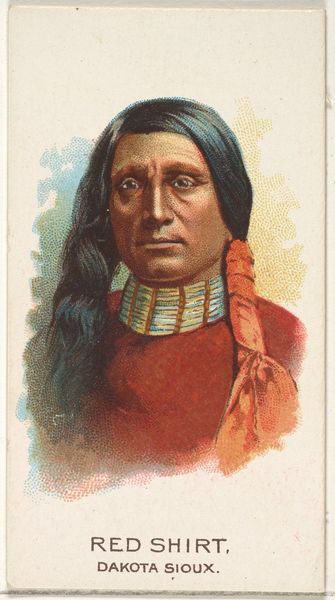

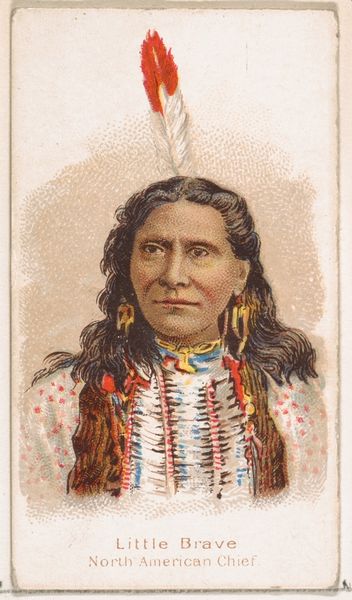

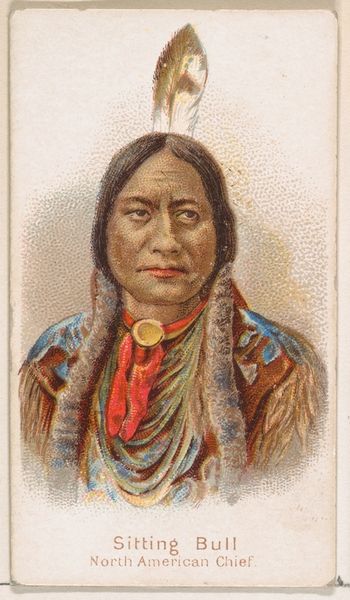

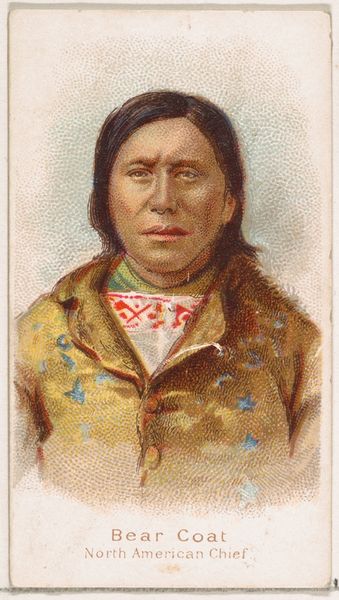

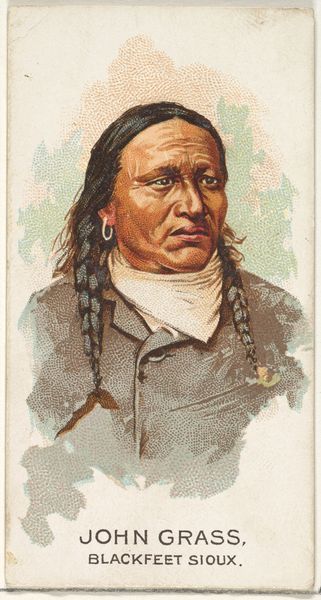

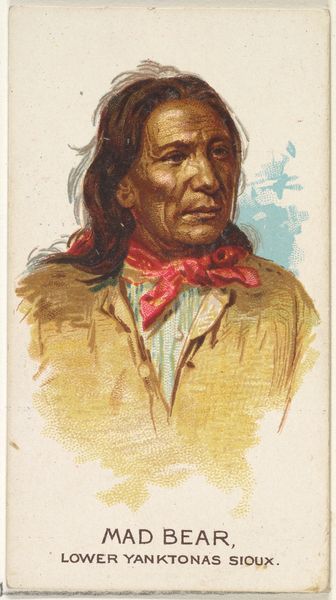

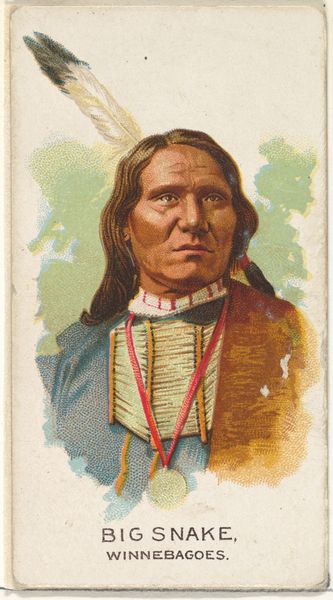

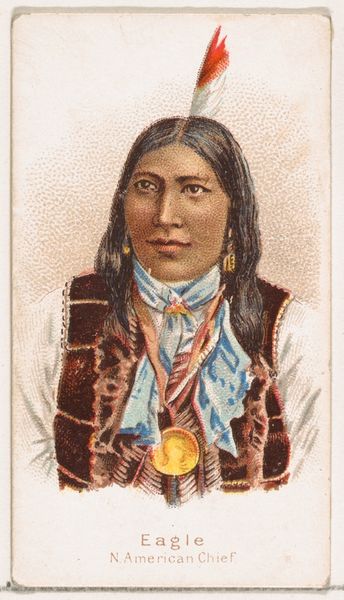

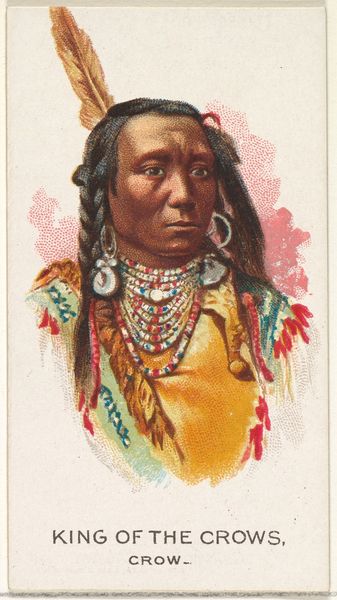

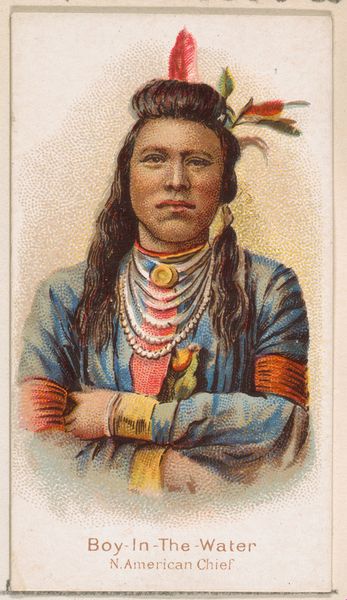

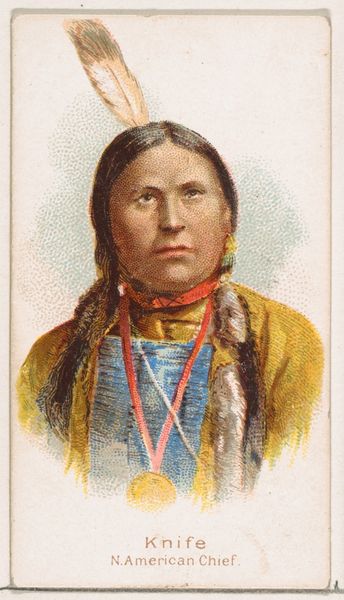

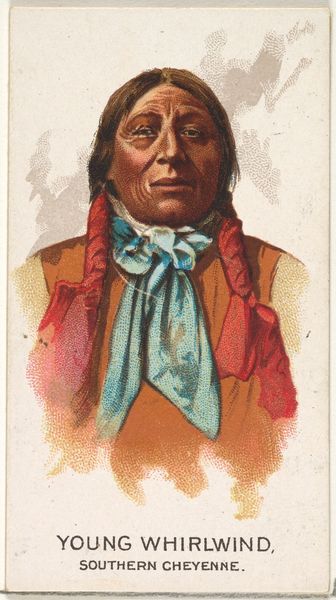

Black Hawk, Dakota Sioux, from the American Indian Chiefs series (N2) for Allen & Ginter Cigarettes Brands 1888

0:00

0:00

drawing, graphic-art, print

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

graphic-art

# print

#

caricature

#

portrait reference

#

coloured pencil

#

academic-art

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 3/4 x 1 1/2 in. (7 x 3.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This striking image of Black Hawk, a Dakota Sioux leader, is a graphic print created in 1888 by Allen & Ginter for a series of cigarette cards. The portrait style gives it an official air, but something about it also feels… exploitative? How should we approach this work? Curator: You're right to sense that tension. The image itself operates on several levels. On the surface, it's a commercial product, but beneath that, it participates in a long history of representing Indigenous people through a colonial gaze. Consider how Black Hawk is positioned: presented as an "American Indian Chief," for mass consumption. This immediately raises questions of authenticity, power dynamics, and cultural appropriation, doesn’t it? Editor: It does. So, it’s not just about the aesthetic value of the image, but also the historical context of its creation and circulation? How were such images used? Curator: Exactly! These images played a role in shaping public perception, often reinforcing stereotypes while simultaneously erasing the complexities of Indigenous cultures. The image becomes a symbol of both admiration and conquest. We have to acknowledge how these representations were—and sometimes still are—used to justify dispossession and discrimination. Does seeing it in this light shift how you feel about the artwork? Editor: Absolutely. I initially saw it as a historical portrait, but understanding its context as a piece of commercial ephemera used to promote cigarettes – alongside its contribution to constructing societal biases against indigenous peoples – makes it much more disturbing. Curator: And that discomfort is productive. It highlights the urgent need for critical engagement with visual culture. By acknowledging the complicated legacy embedded within this seemingly innocuous image, we can hopefully begin to dismantle those very stereotypes it perpetuated. Editor: It’s amazing how much a seemingly simple portrait can reveal about history, power, and representation when viewed critically. Curator: Precisely. That critical lens is essential in understanding and challenging systems of oppression that persist even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.