drawing, print

#

drawing

#

natural stone pattern

#

toned paper

#

abstract painting

# print

#

possibly oil pastel

#

handmade artwork painting

#

tile art

#

coffee painting

#

underpainting

#

men

#

watercolour illustration

#

male-nude

#

watercolor

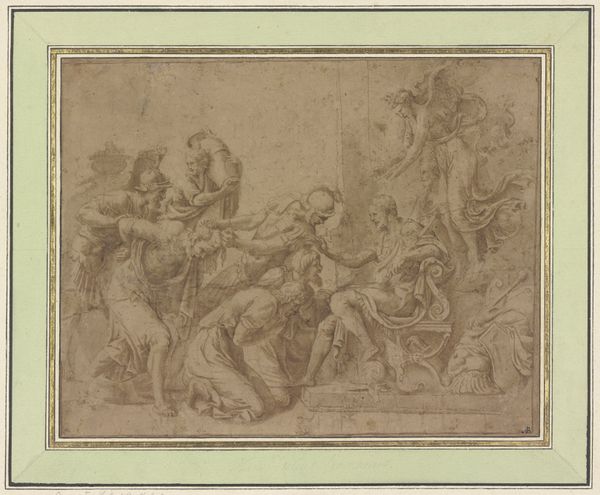

Dimensions: sheet: 7 11/16 x 10 11/16 in. (19.5 x 27.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this is "The Drunkenness of Noah" by Daniel Seiter, dating sometime between 1647 and 1705. It's a drawing on toned paper and quite striking in its portrayal of vulnerability, even shame, within a biblical context. The exposed figure is really the focus, but I’m interested in what the reactions of the other figures signify. How do you interpret this work? Curator: It's a powerful depiction. Considering the source material in Genesis, Seiter uses this scene to perhaps subtly critique patriarchal structures. Think about it – Noah, the patriarch, is exposed and vulnerable, arguably due to his own actions. How might the covering up, or lack thereof, relate to power dynamics, not just within families but within broader society? Editor: That's interesting! So you're suggesting it's more than just a literal interpretation of the biblical story? Curator: Exactly. It's about unmasking authority figures. In art of this period, nudity and drunkenness can be loaded with commentary. Seiter may be inviting us to question who is really seeing, who is acting, and who is being objectified. What happens when the patriarch loses control, and how are those responses gendered, might we ask? Editor: I see. The almost averted gaze of the standing figures... it's not just modesty, but maybe a disruption of a certain order? Curator: Precisely. How does Seiter’s choice of a more intimate drawing, instead of a grand history painting, play into this disruption? What does it mean to expose a 'father' in this way, in this medium? Editor: This really changes my perspective. It's no longer just a biblical scene, but a questioning of societal norms and the vulnerability hidden behind power. Curator: Absolutely. Art provides these openings for challenging the stories we tell ourselves about power, gender, and even divinity. There’s more to the picture than initially meets the eye.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.