print, etching

#

ink drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

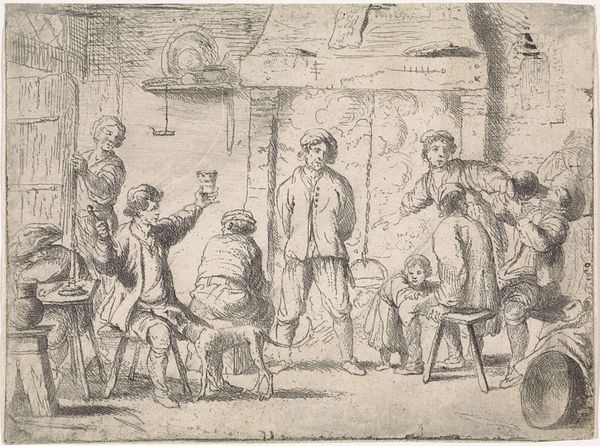

Dimensions: height 117 mm, width 148 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This etching, "Gevangenen in kerker," or "Prisoners in a Dungeon," by Cornelis de Wael, probably made sometime between 1630 and 1648, gives me a sense of stifled energy and quiet desperation. There's a lot of subtle movement depicted within a very confined space. What's your take? What historical context can you offer for how it might have been received? Curator: It’s fascinating to consider how genre scenes like this, particularly depictions of confinement, circulated and were understood in 17th-century Europe. Think about the function of images at that time. Prints, as relatively accessible artworks, often carried social commentary. De Wael, working in Genoa, was surely aware of the political undercurrents concerning justice and social control in the Mediterranean context. Do you notice anything about the varying expressions of the figures and what that suggests? Editor: Yes, some look almost bored, one seems to be communicating through a window, while another seems shackled and utterly dejected. Perhaps de Wael is suggesting that justice, or lack thereof, impacts people very differently, and in the lack of societal mobility. Curator: Exactly. Consider how the print medium itself democratizes the image. It brings the shadowy reality of the prison, often hidden from public view, into homes and public spaces. What effect do you think it would have on viewers to encounter such scenes regularly? It might elicit discomfort and critique regarding institutional power, no? Editor: I can see how circulating images of incarceration might spark a debate about the social systems, human rights, and whether prisons really act as correctional institutions, or something more oppressive. It's made me consider the socio-political power of imagery back then, which extends into the contemporary. Curator: Precisely. It reminds us of how art continues to be instrumental in reflecting and shaping conversations around governance. This piece can thus be thought as part of the broader conversation about human rights and its visualisation throughout history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.