silver, print, photography, gelatin-silver-print, albumen-print

#

aged paper

#

16_19th-century

#

silver

# print

#

war

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

men

#

united-states

#

albumen-print

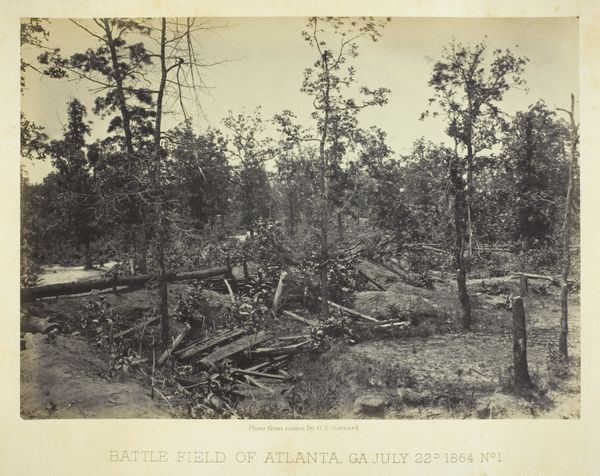

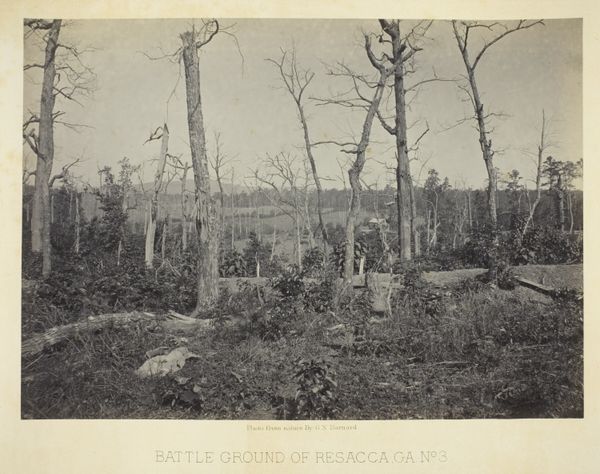

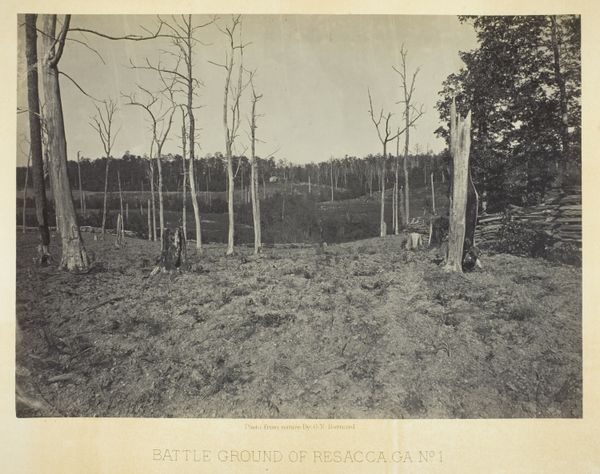

Dimensions: 25.6 × 36.1 cm (image/paper); 41 × 51 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

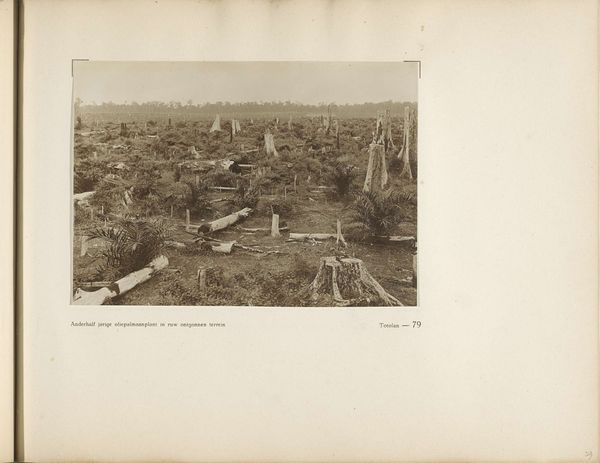

Curator: It’s remarkably still, isn't it? Looking at this gelatin silver print titled "Battle Field of New Hope Church, GA, No. 1," taken in 1866 by George N. Barnard, you’d hardly imagine the devastation. Editor: Stillness... Yes, that's precisely the word. An eerie calm pervades this scene, like holding one’s breath after a scream. It gives me the sensation of suspended time, holding both memory and oblivion. Curator: Absolutely. Barnard was one of the few photographers documenting the aftermath of battlefields during the American Civil War, offering sobering reflections in stark contrast to patriotic glory. He photographed scenes as documents of trauma. What do you read into the photograph’s symbolic geography? Editor: There's a clear delineation here: the raw, uprooted landscape of conflict, giving way to the supposed sanctuary of the church, or perhaps just the suggestion of an abandoned settlement. But notice how even nature itself bears the marks of violence. The light, diffused and somewhat bleak, contributes to a sense of collective mourning. There are very few "men" to actually spot, as if those memories were all but erased. Curator: You're spot on about that light. It evokes a profound sense of loss, even despair, highlighting the disruption of what would otherwise have been idyllic landscape imagery. It's almost a funerary monument of violated terrain. We can’t help but wonder what that empty cart symbolizes in the photograph's distance. Is it escape or death? Editor: That cart... yes, both. These kinds of visual objects act as absences marking the social, cultural, and existential emptiness left behind in the wake of war. Barnard doesn't offer solutions, but stark depictions. Curator: In terms of continuity with images of conflict through time, it makes us question the visual strategies employed when addressing issues of collective suffering and institutionalized violence. This landscape is more than geographical. Editor: Precisely, that brings this piece, made during the 19th century, into conversations around the political implications of viewing spaces touched by systemic violence today. I guess I’ll never quite see these places the same way again. Curator: Indeed. Barnard's stark vista reminds us that the past lingers and reshapes our vision, demanding acknowledgement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.