daguerreotype, photography

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

genre-painting

#

realism

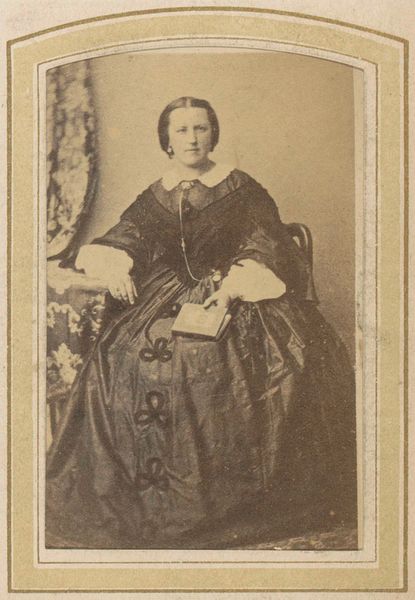

Dimensions: height 89 mm, width 55 mm, height 105 mm, width 61 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Portret van Martha Cornelia Blok," a daguerreotype photograph from sometime between 1850 and 1867. It’s really interesting how the checkered pattern of her dress almost vibrates against the ornate chair. What catches your eye about this portrait? Curator: My focus immediately shifts to the materiality. Daguerreotypes, early forms of photography, involve coating a silvered copper plate and exposing it to light. This wasn’t simply about capturing an image; it was a labor-intensive process. Think about the class dynamics involved: who could afford such portraits, and the societal value placed on representation via emerging technologies. Also, the coloring. The metadata suggests the use of coloured pencil. How does that alter the photographic ‘truth’ we might assume? Editor: So the addition of hand-applied color complicates its status as a purely mechanical reproduction? It isn’t a perfectly objective record anymore. Curator: Precisely! The photographic image becomes an object of craft through the manual addition of colour. Furthermore, consider the labour implied in making her dress: the textiles, the stitching, and the probable social status tied to these materials. Is she the maker of the dress? What were the material conditions of this production? Editor: It does force you to consider all of the people involved in creating not just the image but also everything in it. Were such photos meant to signal a kind of economic standing? Curator: Undeniably. This is not merely a portrait, but a constructed performance meant to advertise the sitter's material wealth. Think also of photography studios arising at that time, and portraiture becoming a new venue for social display. The rise of photography transformed material and social exchange. Editor: I hadn't really considered the photograph as part of a network of production, but that totally reframes how I see it now. Curator: Indeed. By analysing materials and the labor intertwined within the image, a simple portrait transforms into a window to broader social and economic currents.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.