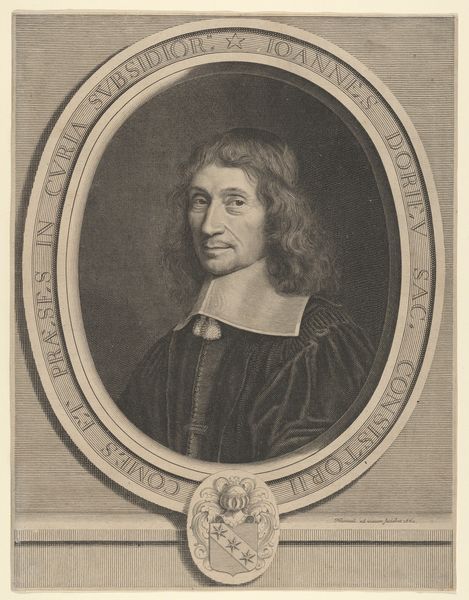

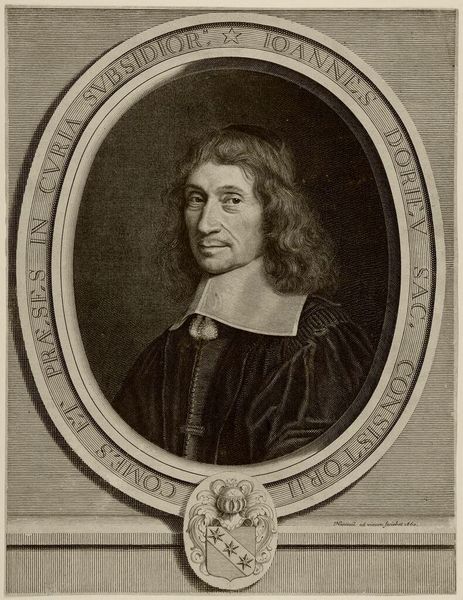

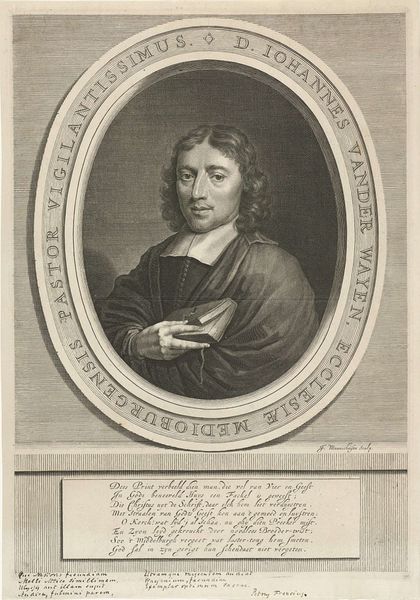

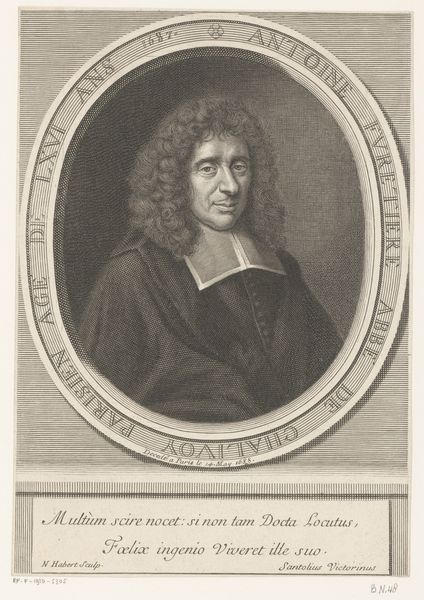

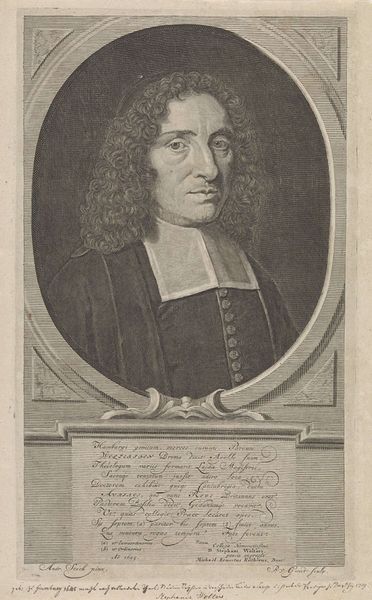

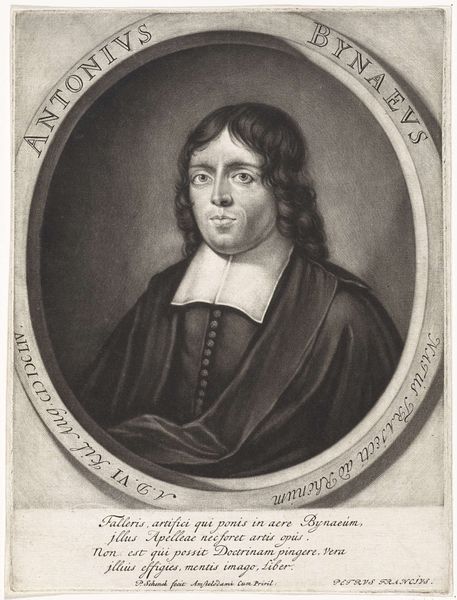

print, intaglio, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

intaglio

#

old engraving style

#

historical photography

#

portrait reference

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 388 mm, width 257 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

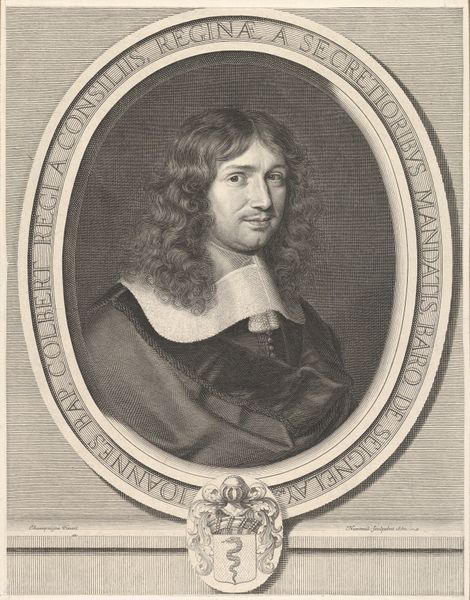

Editor: This is "Portret van predikant Joannes Vollenhove," made between 1679 and 1717 by Abraham de Blois. It’s an engraving, an intaglio print held at the Rijksmuseum. It feels…stately, but also a bit severe. What historical factors shaped the making of such a portrait? Curator: Considering the period and the sitter, Joannes Vollenhove, a theologian, this print served a very public function. It disseminated his image, solidifying his authority and presence within the church and society. Notice the ornate frame—how does that impact its accessibility to wider audiences? Editor: I suppose the elaborate frame and Latin inscription reinforce his importance to learned circles. It isn’t exactly for mass consumption. Was there an active market for such prints? Curator: Precisely. The market for portrait prints was quite robust in the Dutch Republic. Think about the rise of the middle class and their aspirations to emulate the elite. Commissioning or buying such prints was a way to participate in that culture of visibility. Who controlled the narrative conveyed? Editor: It feels like both the sitter and the institution he represented shaped the narrative – a sort of controlled public image. Something for the Church. Curator: Indeed. Now consider how these prints circulated – often bound in books, displayed in homes. Each context alters its meaning slightly, shifting from a tool of institutional power to a marker of personal piety and cultural capital. Did you note how that is different from a modern photo or post of an important person? Editor: Very true. The different ways this image was viewed impacts the context of this man’s life. Curator: Absolutely. It highlights how art is not created in a vacuum but actively shaped by the social, cultural, and institutional forces of its time. Editor: That really changes how I look at portraits now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.