Dimensions: sheet: 25.3 x 20.4 cm (9 15/16 x 8 1/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

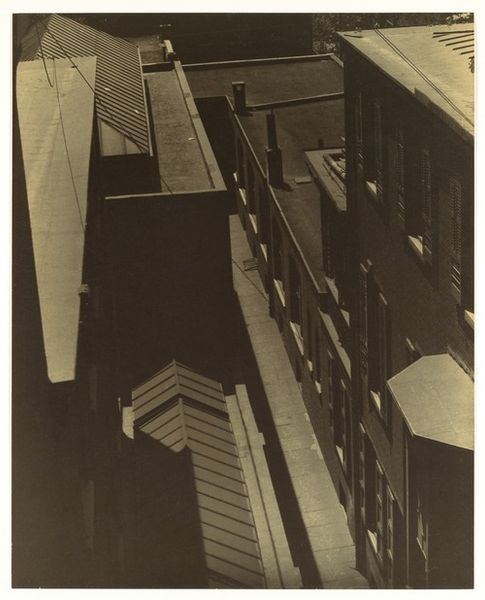

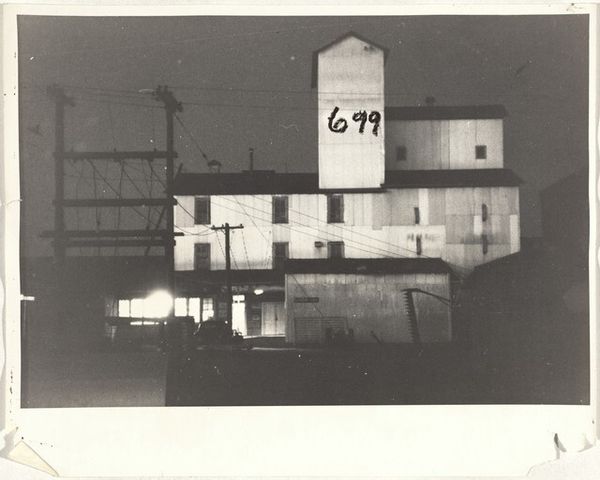

Curator: This gelatin silver print, "Salt Lake City, Utah," was captured by Robert Frank in 1956. It's part of his seminal work, "The Americans," a series that challenged conventional representations of American life. Editor: My first impression? A stark contrast. We have this almost brutalist monument dominating the foreground, juxtaposed against what appears to be a very formal, old-fashioned building up on a hill. There's a sense of… displacement, maybe? Curator: That contrast is key. Frank's work often juxtaposes elements of Americana in ways that are both revealing and unsettling. Here, he plays with visual hierarchy. The ornate building, probably meant to convey civic pride, is dwarfed and overshadowed by this almost aggressively modern structure. Editor: And it’s the 'School of Art' that adds an ironic dimension. The old institution being symbolically overshadowed by a stark utilitarian design, that tension must've been a tangible anxiety felt throughout postwar American society. Curator: Exactly. It reflects a broader tension of the era: tradition versus progress, high culture versus mass culture, all caught within Frank’s characteristic snapshot aesthetic, which was so groundbreaking at the time because he wasn't afraid to tilt, blur, or crop a photograph, much to the chagrin of institutions at the time. Editor: You see it everywhere here – from that strange spherical object atop the brutalist structure, to the number scrawled in the top right of the image that feels like an outtake from something like Walker Evans American Photographs that also became something important itself as art. It captures, even celebrates a kind of imperfect moment. It's fascinating how this one image can be a loaded statement about institutional authority, or at the very least invites a deconstruction of it. Curator: Frank’s vision was deeply influential, democratizing photography in a way, pushing its boundaries by injecting realism into visual language to represent modern life during that time. He captures the way Americans present themselves while hinting that maybe things are a lot less wholesome under the surface. Editor: I agree, it still resonates. The photograph invites us to question what we consider to be visually important, but, more crucially, to whom the built environment truly caters. Curator: A potent statement then, and even now. Editor: Indeed, something about its enduring mystery leaves us wanting to reconsider history and maybe rewrite the script.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.