drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

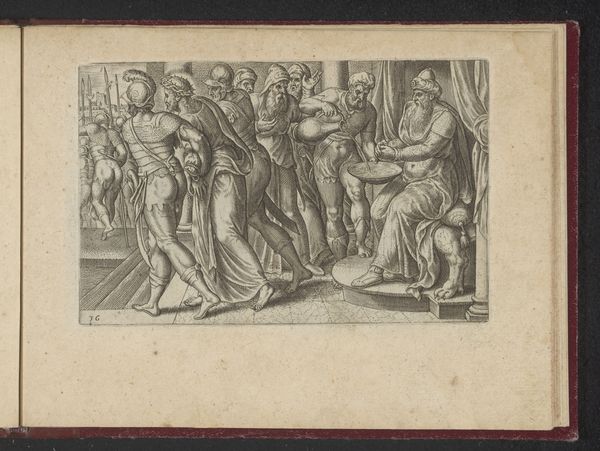

Dimensions: height 92 mm, width 139 mm, height 137 mm, width 183 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

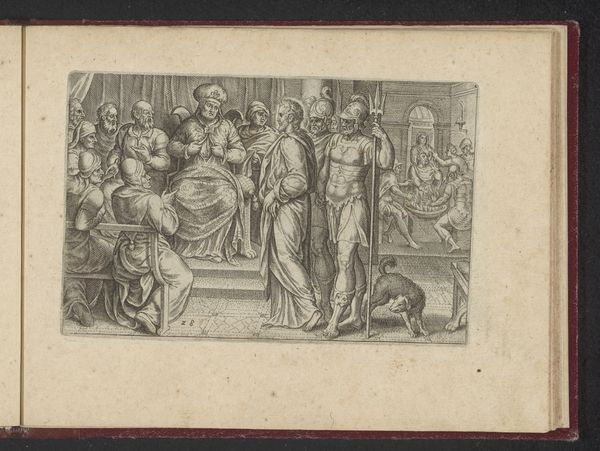

Curator: This is Philips Galle’s "Christus voor Annas," an engraving made in 1573. What's your initial impression? Editor: Oppression, definitely. The crowded composition, the unflinching gaze of Annas… it creates a palpable sense of powerlessness. Even the little dog adds a disturbing note; he looks mangy and seems to reflect society’s moral decay at the time. Curator: Yes, the piece certainly depicts a scene heavy with consequence. Galle's use of line and the contrasting light and shadow contribute to this impression, building up a visual language resonant with the anxiety and spiritual turbulence of the Reformation. Editor: Right, that’s crucial. We must remember that Galle worked during a period when religious and political structures were rapidly shifting. This depiction of Christ before Annas, therefore, can be seen as an exploration of resistance against illegitimate authority. Curator: It speaks to a potent, long-standing symbolic tradition. Annas, high priest, becomes a complex signifier. On one level he embodies established religious order, but perhaps he stands for human hubris, flawed interpretation. It recalls iconoclastic impulses that resist what they see as flawed idolatry. Editor: Absolutely. Galle presents us with a visual articulation of religious and societal hypocrisy, revealing how power can corrupt even those who claim divine sanction. Note, too, how Christ’s bound hands symbolize the suppression of truth. It all points to a subtle critique of institutional authority that resonated powerfully in his time and does even now. Curator: The Mannerist style itself adds another layer. Elongated figures and dramatic gestures can communicate deep feeling beyond naturalism. Editor: Indeed. And the Northern Renaissance love of detail, particularly evident in Annas' attire, only emphasizes his worldly status and further isolates Christ. The engraving method allowed prints to spread widely, taking these revolutionary ideas to the masses. This artwork has its own biography in the history of its era. Curator: By examining Galle’s piece, we engage in a deeper study not only of a crucial religious episode, but also with our evolving concepts of moral legitimacy and religious institutions in art. Editor: Precisely, making these images both artifacts of the past, and living commentary on today's urgent sociopolitical themes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.