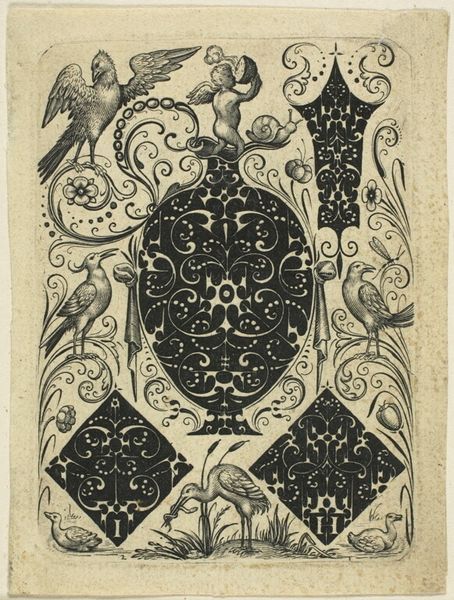

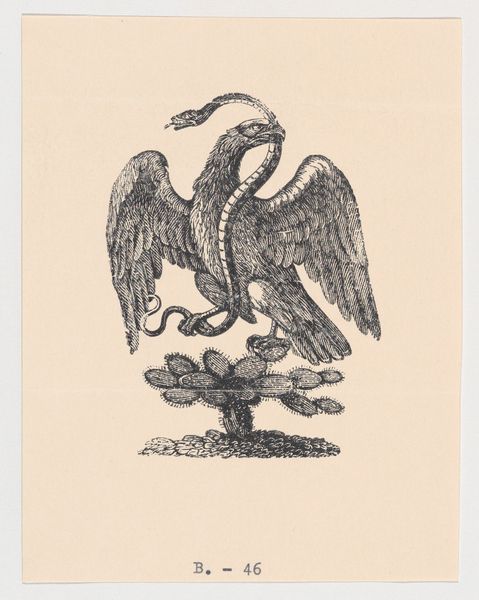

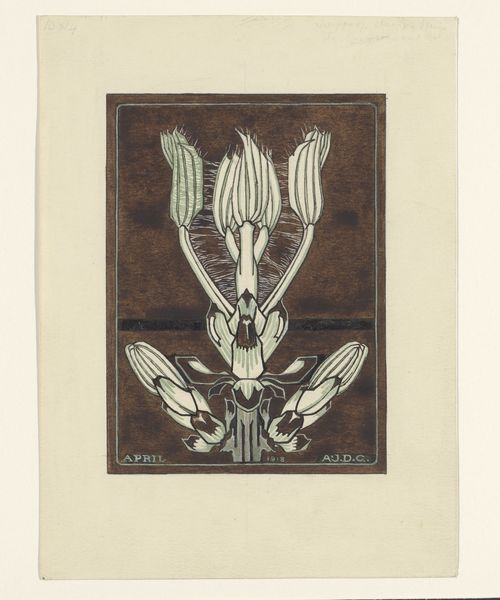

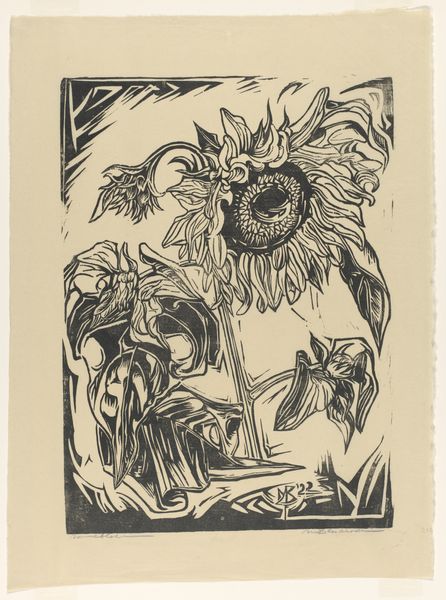

drawing, print, woodcut

#

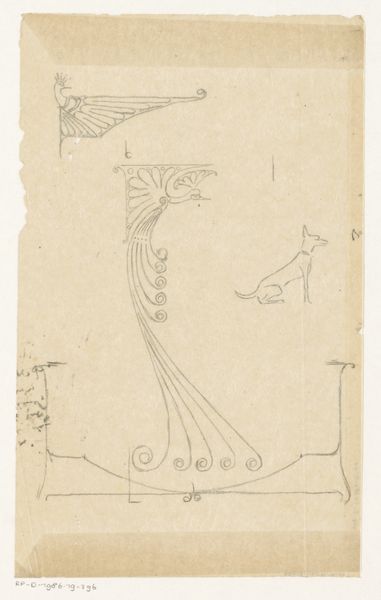

drawing

#

art-nouveau

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

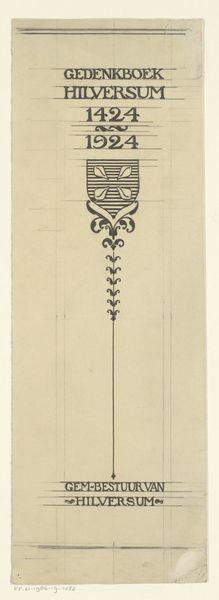

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

botanical drawing

#

woodcut

#

pen work

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 131 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

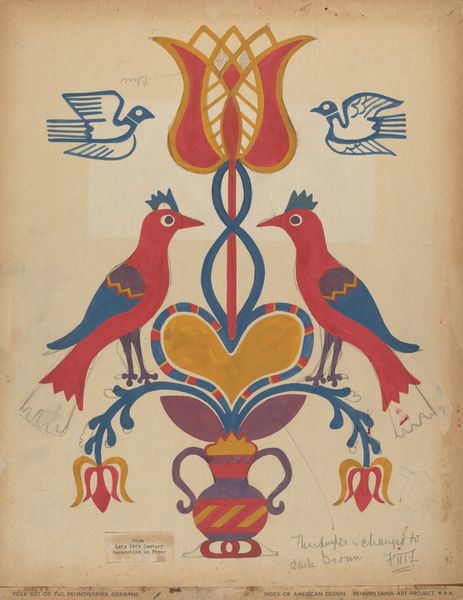

Curator: Welcome. Today, we're exploring "Vlinder, haan en bladwerk," which translates to "Butterfly, Rooster, and Foliage," a print believed to have been created by Julie de Graag sometime between 1901 and 1905. Editor: Immediately striking is the composition: these seemingly disparate elements, rendered in that single, warm sepia tone against the cream paper… there's a quiet whimsy here. A stillness, almost meditative. Curator: De Graag worked within the currents of the Dutch Art Nouveau movement, and this work certainly showcases key characteristics. Notice how she employs stylized natural forms—the butterfly, the rooster, and those highly stylized leaves—integrated into a flattened, decorative space. Consider the rise of decorative arts at this time. Editor: Absolutely, but I see something more here than mere decoration. The butterfly, the rooster – these are loaded symbols. The butterfly signifies transformation, the ephemeral nature of life. And the rooster? A symbol of vigilance, even masculine pride, positioned rather pointedly below. I am particularly drawn to her approach towards line. Curator: Indeed. There is an almost orientalist sensibility. Influences came from many places at this moment. Think about the colonial and exhibitionary contexts that impacted this kind of decorative visuality, making work like this so popular among bourgeoise consumers. Editor: Yes, but beyond that specific cultural reading, what does it signify? This controlled expression, of nature, femininity, and its interplay with notions of power. Curator: It prompts an interesting question. The piece, being a print, also hints at ideas around reproducibility and distribution—art entering into the everyday. How the Art Nouveau was meant to touch all aspects of modern life, not just the elite sphere. Editor: And I wonder, with De Graag's choice of subject matter—these emblems of nature presented in such an arranged, almost codified manner—is she subtly challenging or reinforcing conventional representations of gender and nature in a rapidly modernizing world? Is she appropriating masculine symbolic representation? Curator: These kinds of questions are invaluable, it's true. This piece encourages one to delve into both the historical contexts of production as well as theoretical frameworks for understanding these themes. It’s a piece where formalism and historical thought clearly intertwine. Editor: I find that by juxtaposing form with cultural context and symbolic weight, this piece delivers far more impact than it suggests upon first viewing. Curator: Precisely.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.