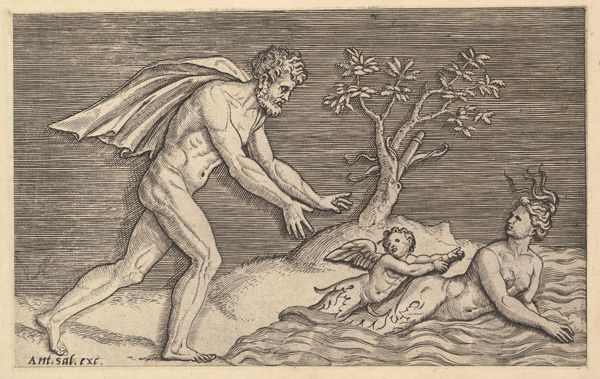

print, engraving

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 108 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, attributed to Marco Dente, dates from between 1498 and 1532, during the Italian Renaissance. The title is "Galatea escaping Polyphemus". It's an engraving on paper, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. What's your initial impression? Editor: Stark. The limited medium lends itself to an almost diagrammatic representation, a coolness that mutes the overt drama of the scene. It's intriguing that this narrative is stripped down in such a way. Curator: Well, think about printmaking in the Renaissance. It was revolutionary! This wasn't just about illustrating a classical story; it was about dissemination. Engravings like these made stories and styles accessible to a wider audience than ever before. Consider the market for images then—prints were a relatively affordable way to acquire art. Editor: Absolutely. And look at how the labor is presented. The figure of Polyphemus seems monumental, static, almost burdened by the material world that surrounds him. Contrast that with the fluid dynamism given to Galatea and even Cupid. Is Dente using these opposing bodies to elevate the nymph? Curator: Yes, I'd agree. Galatea’s almost weightless, conveyed through Dente's skillful rendering of drapery and the swiftness of her seashell chariot, fleeing a besotted and enraged Polyphemus. But even the lines forming the water convey movement, a purposeful act. Editor: How interesting, as it mirrors the swiftness with which this story was brought to people at the time. So is this a celebration of both technical skill and of making Ovid's narrative of sexual pursuit mobile to audiences in the 16th Century? And perhaps of Galatea's victory through this constant reproduction of her own narrative? Curator: Perhaps, though her "victory" seems provisional here. Polyphemus's bulk dominates a full half of the print! The image really asks how we participate in image production and consumption, and how these impact society's narratives of power. Editor: Agreed. Considering that prints in those days were often hand-coloured afterward, one can easily imagine people purchasing and customizing this artwork in a number of different ways. Thank you; that certainly sheds light on this historical artwork. Curator: My pleasure. I appreciate your take on the artistic choices behind production of this engraving.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.