Dimensions: 29.8 × 60.6 cm (11 3/4 × 23 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

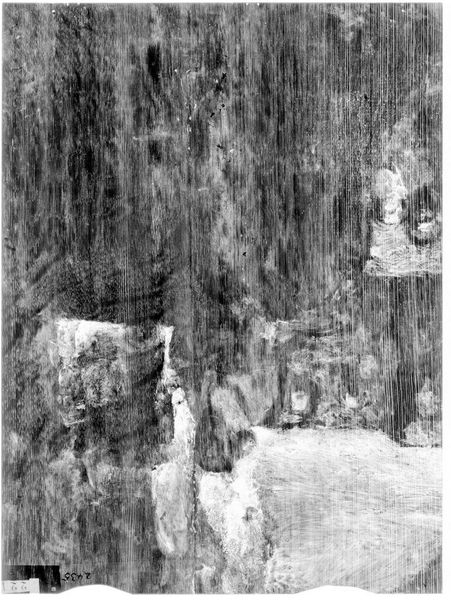

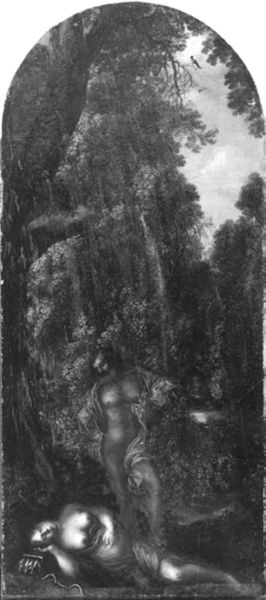

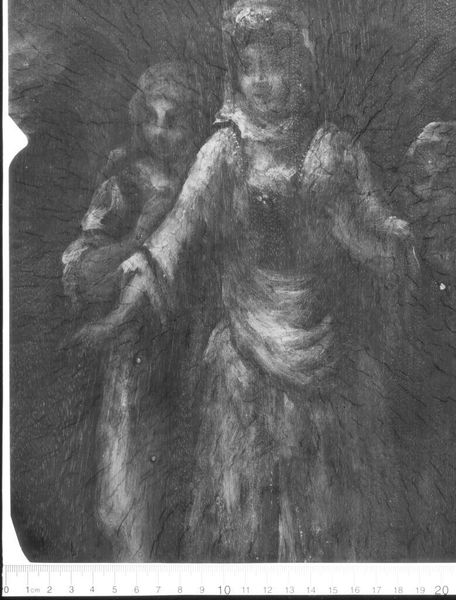

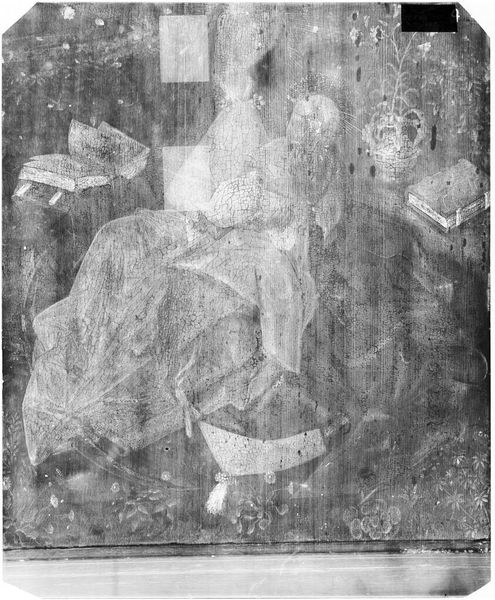

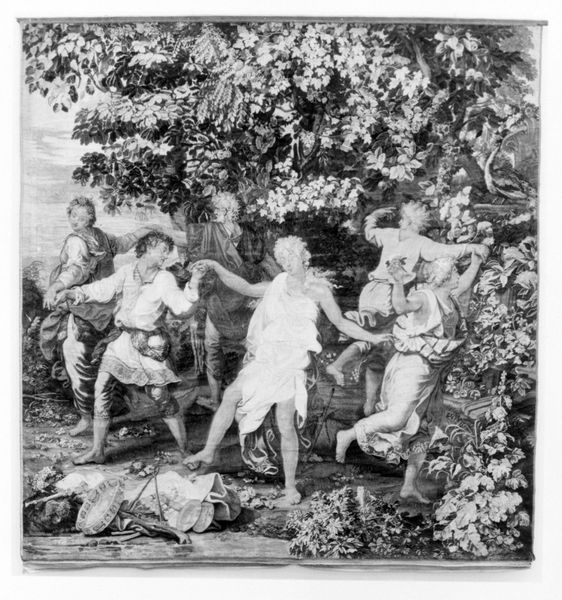

Curator: Monticelli’s "The Princesses," circa 1870. It hangs here at the Art Institute of Chicago, a fantastic example of his richly impastoed style. What springs to mind for you when you see it? Editor: My first thought? It’s a secret garden teeming with unspoken narratives. There's almost a ghostly feel, wouldn't you agree? The texture practically swallows the figures whole. Curator: Exactly! It's pure, almost reckless abandon with paint, like he's sculpting with oil. I see hints of Fragonard and Watteau—fêtes galantes with a raw, almost feverish intensity. This isn't polite society; it's a simmering drama just below the surface. I see a woman, almost kneeling, in the forefront and, beyond, many women together with a man wearing a top hat. The image quality, even when one is standing right in front of the piece, it's only possible to appreciate Monticelli's vision as the figures begin to take shape out of the textured depths of his materials. Editor: That "simmering drama" speaks volumes to me. Who are these princesses, really? Are they symbols of idealized femininity, or is Monticelli subtly critiquing the gilded cage of their existence? Their ghostly appearance reminds me of how easily women have been erased from history or romanticized to the point of being unrecognizable as full human beings. Curator: A gilded cage... I love that. He certainly isn't idealizing them. There's a certain sadness to the figures. Perhaps reflecting his own turbulent life and struggles? The impasto acts almost as a veil, obscuring and revealing simultaneously. I wonder what we miss because the material gets in the way. And then, the fact that it is not called "princess," in the singular. Pluralizing this artwork title suggests the commonness of a phenomenon. It also calls attention to how such princesshood is imposed on them, like a type of forced assembly or social expectation. Editor: Absolutely, a material barrier! Think about the limited roles available to women during that era. The surface might reflect those suffocating constraints. Monticelli’s process underscores their predicament – caught within layers of expectation and social performance. The impasto, like layers of courtly garments, serves not just as a creative style but also speaks to lived social conditions and norms. Curator: I had never thought about it like that! He died impoverished. The world largely failed to see the worth in these pieces, too. Editor: Makes you think, doesn’t it? Perhaps art becomes activism when it disrupts dominant narratives, forces us to look closer, and, especially, if it reveals some truth about the human condition through unusual choices of technique and style. Curator: Well said! I will walk away now pondering how Monticelli might be even more relevant now than ever.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.