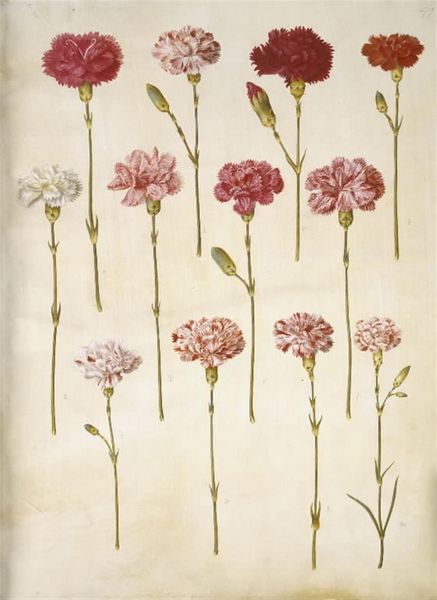

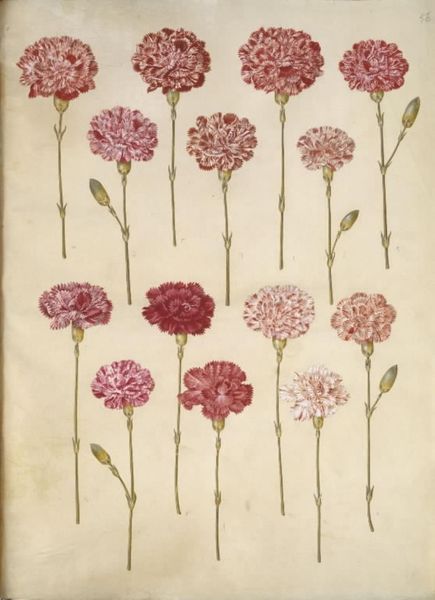

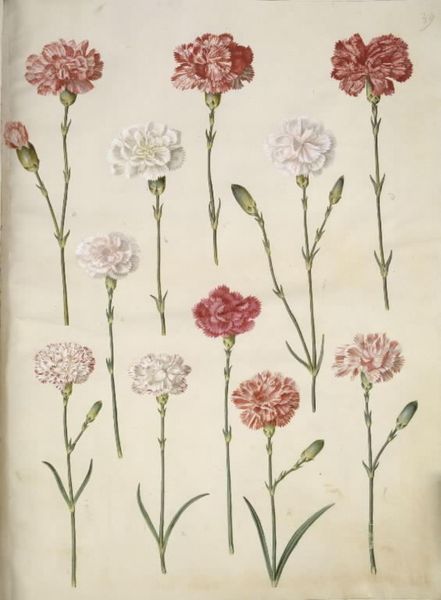

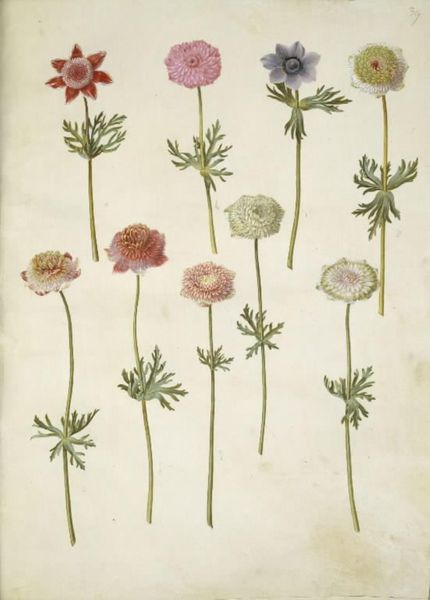

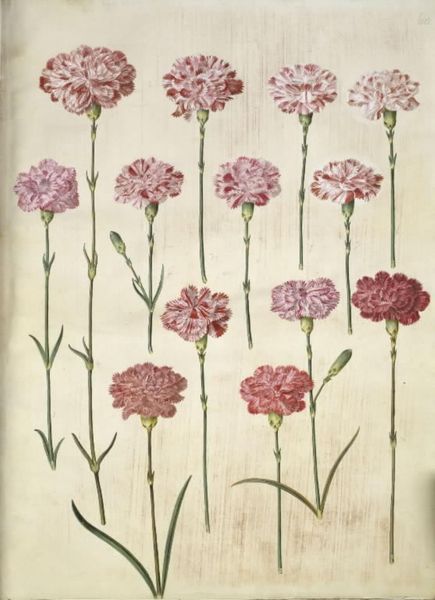

drawing, gouache, watercolor

#

drawing

#

water colours

#

gouache

#

11_renaissance

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 505 mm (height) x 385 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Take a look at this exquisite botanical illustration. The State Art Museum holds this piece entitled "Dianthus caryophyllus (have-nellike)", completed sometime between 1649 and 1659 by Hans Simon Holtzbecker. It's crafted with a delicate combination of drawing, watercolor, and gouache. What's your initial take? Editor: There's an intriguing formality, almost like a carefully posed group portrait. But the colour palette is unexpectedly rich – the shades of red against the muted backdrop makes me think about fragility. Are they pressed or perhaps even dried? There's a curious tension between vibrant life and impending mortality. Curator: It's fascinating you mention that tension. Botanical illustrations served varied purposes back then. While admired for their aesthetic qualities, they also played a crucial role in scientific documentation, recording variations of specific flowers, similar to collecting data. Editor: So, what does it mean that we see rows of nearly identical flower blooms? How should we read the uniformity on display? Is this an expression of controlled natural aesthetics to mimic the societal and court system, of Holtzbecker's time? Curator: Yes, Holtzbecker’s position in the court likely influenced this detailed depiction. There was high demand for botanical art, fueled by wealthy patrons seeking both knowledge and status. These illustrations became symbols of prestige, scientific advancement and luxury. They certainly offered ways of subtly conveying wealth, power, or allegiance within social circles. Editor: It also is an intersectional narrative that touches upon questions of land ownership, labour, and colonialism. Many botanical collections from this era reflected the expanding reach of European powers, and the commodification of natural resources. How complicit was the artistic eye in this? Is this how wealthy patronage perpetuates these forces? Curator: The connection you draw to the era's colonial ambitions is quite relevant, considering the global movement of plants during that period. However, it also speaks to the developing understanding of the natural world and a growing field of scientific illustration. It is interesting to unpack Holtzbecker's motivations and intentions behind such controlled art that could speak about wider global structures. Editor: True, this flower represents the human impulse to classify, own, and celebrate the natural world all at once. And maybe there’s a bit of melancholy in acknowledging that even beauty gets framed by power. Thanks for that added layer. Curator: Thank you for pointing out this painting’s relevance within the history of colonial movement. A pleasure as always.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.