print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

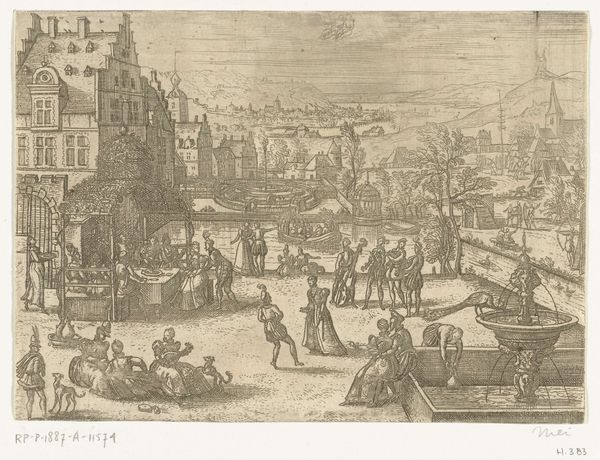

Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 114 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, titled "Feestend gezelschap in een stad" or "Festive Crowd in a City," comes to us from the Dutch Golden Age and is attributed to Adriaen Matham. It's an engraving, dating from somewhere between 1620 and 1660, now held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression? Chaos, but of a joyful sort. It’s a really bustling composition; everyone's crammed together, like a freeze-frame from a festive riot. I’m wondering, looking at this print’s line work, about its reproducibility and function… Curator: It absolutely bursts with narrative potential, doesn't it? I find myself drawn to the figures in the foreground—the dancers, the embracing couple. This kind of genre scene can tell us so much about the social norms and structures of the time, like public celebrations. Who was included, who was excluded, who was involved and who was excluded based on social class, race and even sexuality. Editor: I’m more taken by the cityscape itself – the gate, the waterway, the buildings rendered in detail, and that striking effect with the rays of light emerging from the horizon. Thinking about the production of this engraving – what sort of workshop created it? Where did Matham get his materials? What processes are implemented in an age where "craft" hadn't become fine art? This level of labor surely had social meaning. Curator: Certainly! Consider, too, how a print like this might circulate – as a commodity, of course, but also as a kind of visual propaganda, promoting a certain ideal, or perhaps even subtly critiquing the status quo, which invites the question, what sort of critical discourse can be read in these bustling crowds? Does Matham have some subtle reading on the dynamics of its urban landscape. Editor: That brings to mind questions around consumption and class – who could afford these prints? And where would they hang them? Were such images used as decorations on the street, as popular forms of expression for public audiences who had far less resources at their command than the rising mercantile classes? Curator: Precisely. Analyzing from the vantage point of power dynamics, do the celebratory aspects represent a true breaking away from established hierarchies or perhaps a brief but superficial escape before the system continues to exert its power on marginalised groups, keeping it the subject’s reality? Editor: Well, even considering the details of materials, Matham likely depended on the patronage system, making us look critically at who shaped not only distribution but also the art, which demands consideration of whose perspectives are prioritized and preserved in these visual materials. Curator: Reflecting on it, these images give us a really rich entry point to studying and understanding the relationship of that age’s power structures to those celebrations! Editor: And from that entry point, we can better understand not only the means of its making but its very existence.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.