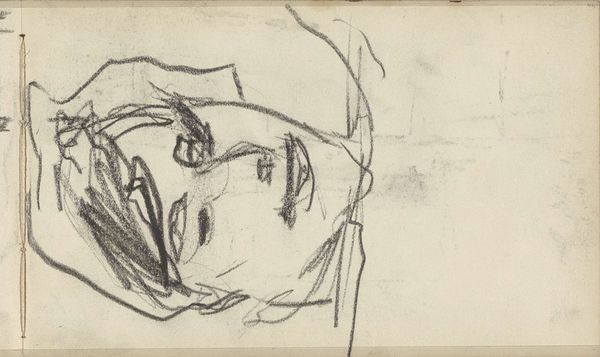

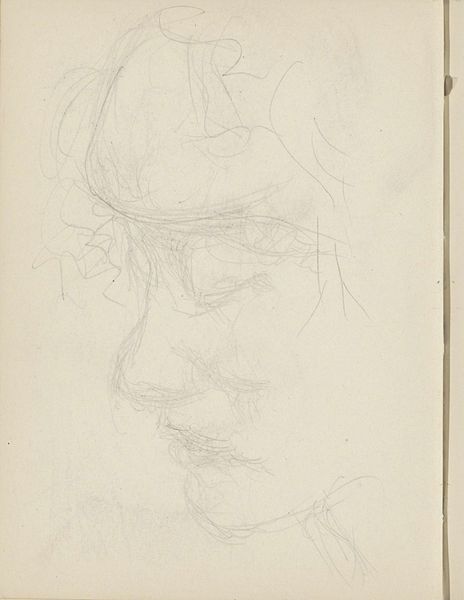

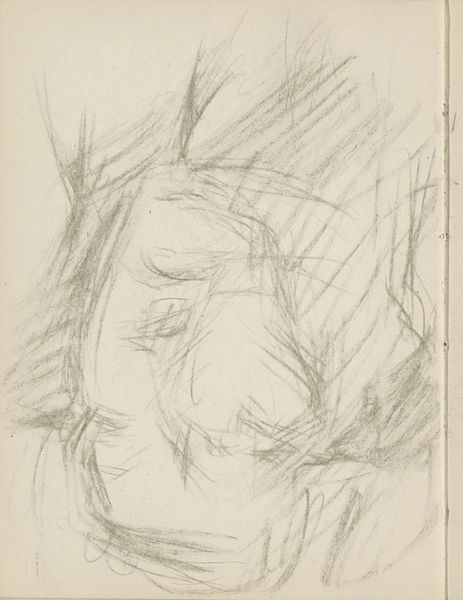

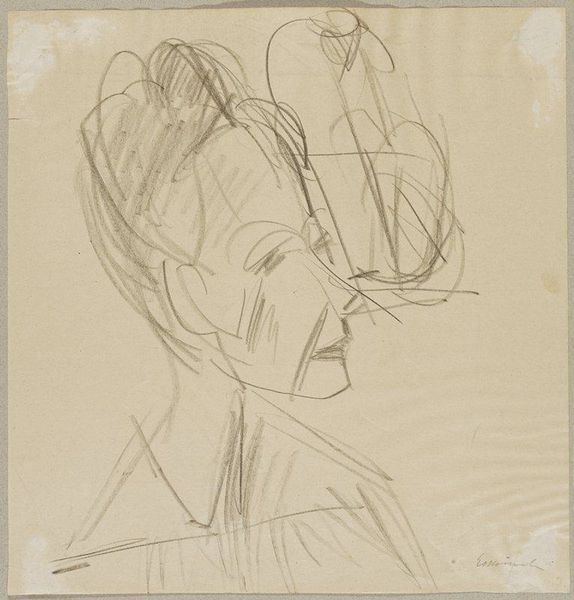

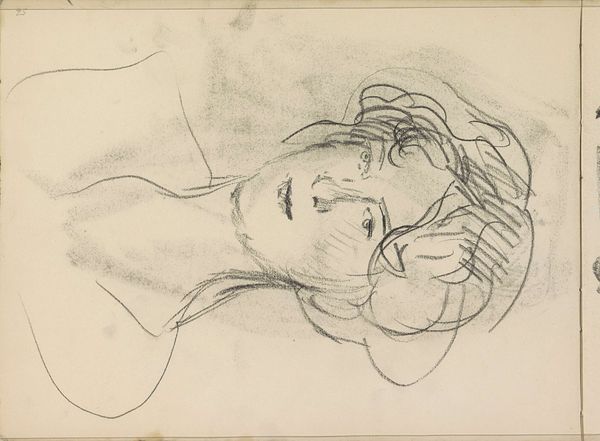

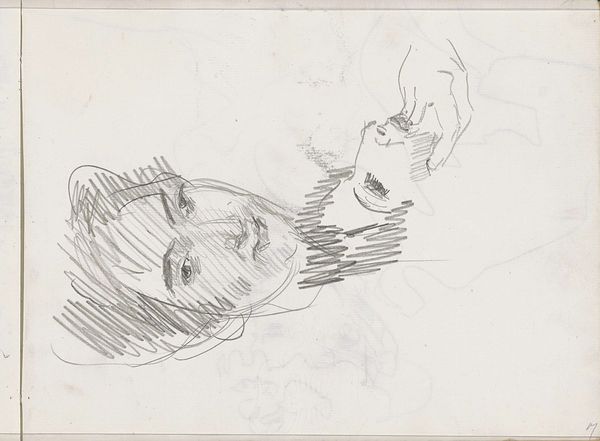

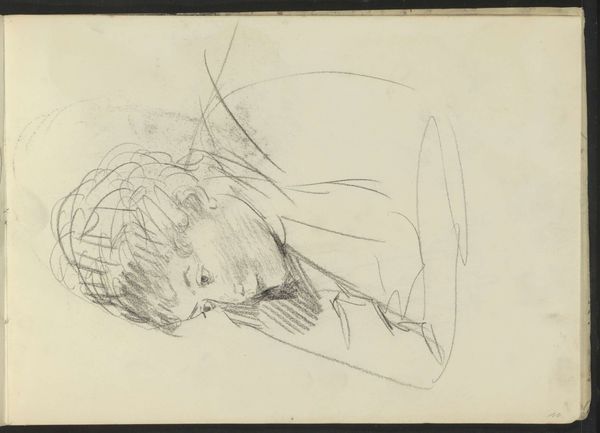

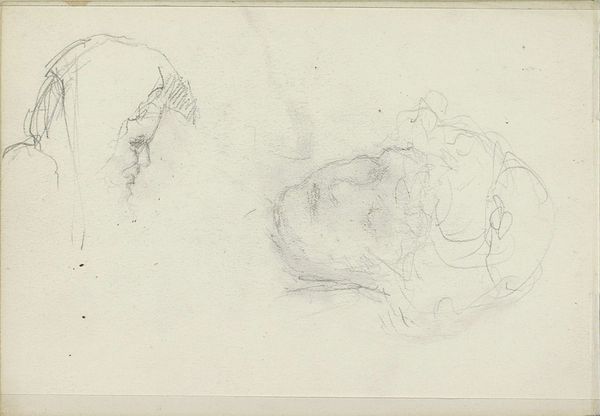

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

imaginative character sketch

#

light pencil work

#

impressionism

#

incomplete sketchy

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

character sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

profile

#

realism

#

initial sketch

Dimensions: height 116 mm, width 192 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a fascinating sketch! This is "Vrouwenhoofd," or "Head of a Woman," a pencil drawing by George Hendrik Breitner, created sometime between 1887 and 1891. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought is "unfinished"—in a compelling way. The loose lines, the delicate shading… it feels like a glimpse into the artist’s thought process, the genesis of an idea. Curator: Precisely! Let's consider the materiality. The stark contrast between the humble graphite pencil and the presumed paper—probably relatively inexpensive stock for preliminary work. This underscores the importance of sketching as a fundamental step in Breitner's process, reflecting artistic labour and the making of art. It also challenges that high-art, low-art binary. Editor: And given that Breitner worked during a time of social upheaval and industrial change, the availability and affordability of materials would certainly have influenced artistic production. How did societal perceptions of women impact portrayals like this? Is it an intimate portrait, or a more generic study? Curator: Good questions! Breitner, working during the rise of photography, aimed to capture the raw, unfiltered realities of Amsterdam life. While known for cityscapes and scenes of working women, drawings like these were crucial studies. They were private endeavors providing insight into constructing visual narratives reflective of society at the time. These pieces helped shape perception by presenting unfiltered views on class and social structures, often sidelining the more conventional ideals of beauty evident in institutional portraiture. Editor: It's compelling how a seemingly simple drawing becomes a point of access to wider cultural and political factors influencing not just the creation, but the understanding and representation of a subject in art during a very specific moment. This drawing certainly shows Breitner exploring a concept. I get a strong sense of quiet introspection. Curator: It does invite introspection doesn't it? To really appreciate a seemingly insignificant sketch is actually a reflection of a whole social history within constraints of production, labor, the materials used, as well as of artistic interpretation and political setting. Editor: Exactly! Considering all the dimensions in play at once enriches our encounter and understanding, which makes art truly meaningful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.