daguerreotype, photography, architecture

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

outdoor photography

#

photography

#

islamic-art

#

architecture

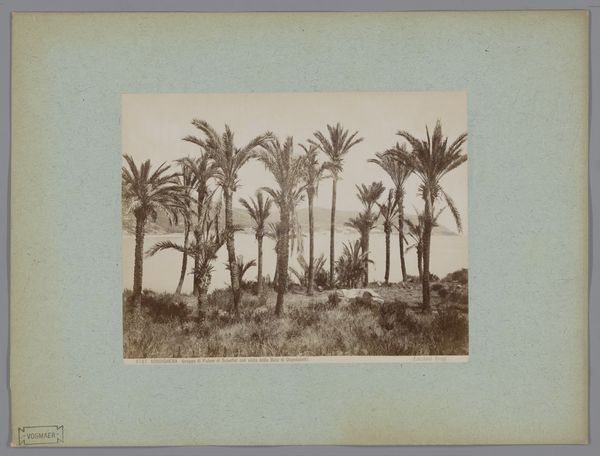

Dimensions: 24.0 x 30.3 cm. (9 7/16 x 11 15/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

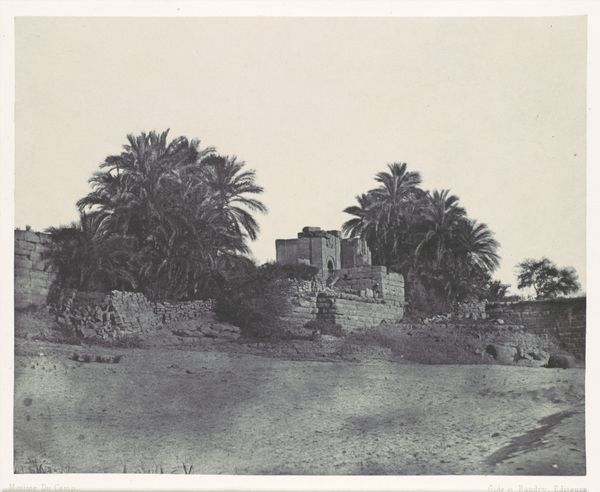

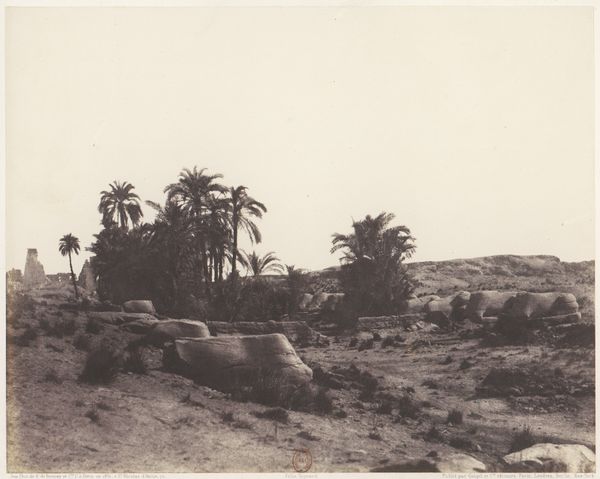

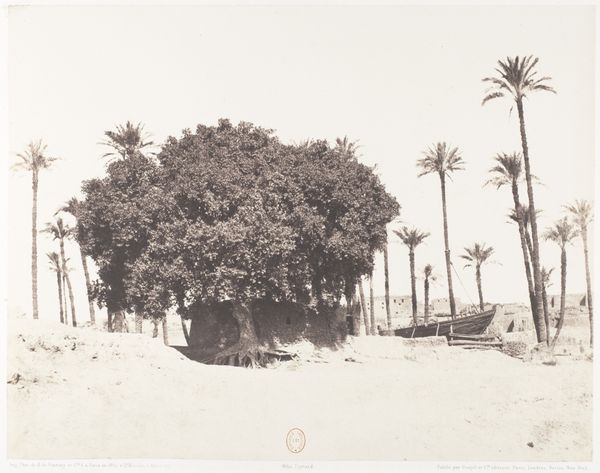

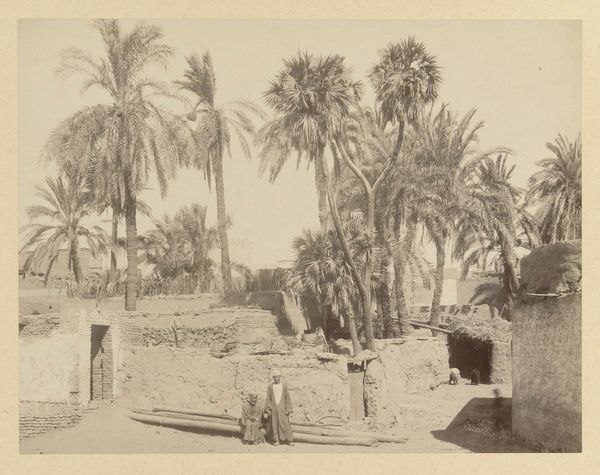

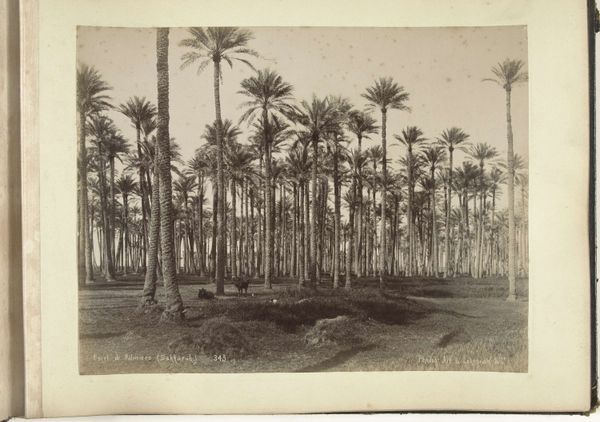

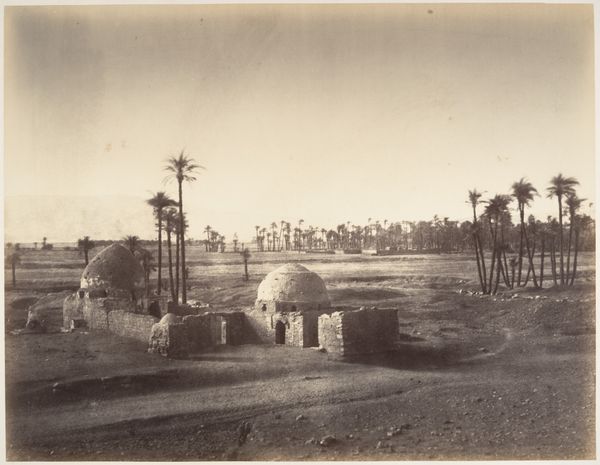

Curator: Looking at Félix Teynard’s daguerreotype, "Abâzîz, Intérieur d'un Village Arabe," made between 1851 and 1852, the weight of history feels palpable, doesn't it? Editor: It certainly does. I’m immediately struck by the texture. You can almost feel the coarse material of the crumbling structures, the grit of the earth. It speaks to the labor involved in its construction and, frankly, its subsequent decay. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the social context—France’s burgeoning interest in Egypt during that period, a complex web of fascination, Orientalism, and colonial ambition. The village interior, captured with such detail, exists within this gaze. Editor: The gaze being a specific process of material capture using light-sensitive chemistry. Daguerreotypes were a novel technology then. We see a tension here, the scientific means and the colonial power structures simultaneously at play. Curator: Indeed, photography itself was a tool of documentation, and Teynard, through his lens, participated in shaping the Western understanding and representation of the Middle East. We see an idealized ruin, if you will, of Arab life that reinforces particular narratives. Editor: I agree. We also have to acknowledge the material circumstances that led to this particular image: the preparation of the plate, the exposure time, and Teynard's logistical and financial capability to access and capture such a landscape at this time. These considerations shift the emphasis to production conditions that should also be scrutinized. Curator: That adds depth to our reading. Look closer—the positioning of palm trees acts almost as framing devices, and how the artist employs light and shadow gives a romantic, painterly feel to what might otherwise have been a mere record. What sort of narrative does that promote? Editor: A narrative deeply entangled with exoticism and hierarchy. Ultimately, it seems important to consider the processes—historical, cultural, material—that were necessary to produce not only this image but our very understanding of it now. Curator: Reflecting on this image, I’m reminded of how art serves as both a mirror reflecting prevailing ideologies and a lens that, if examined critically, can help us deconstruct the narratives it perpetuates. Editor: And how those prevailing ideologies were enacted by material things and artistic labor. Recognizing both empowers us to construct more complete understandings of the past and its present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.