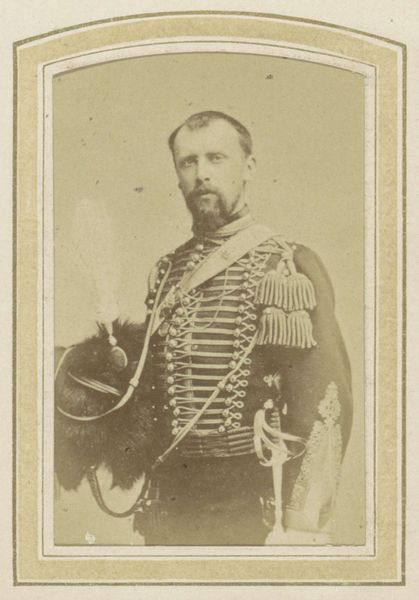

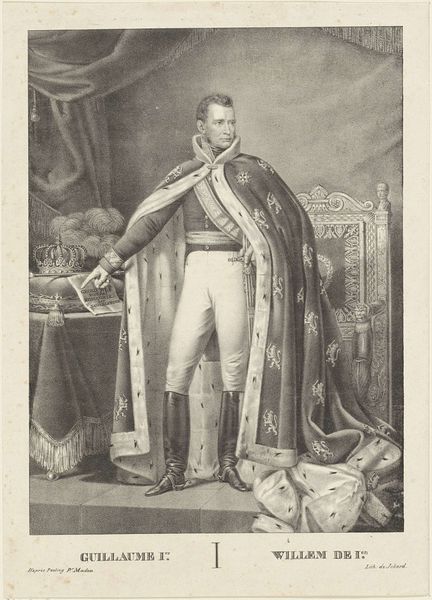

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

history-painting

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 163 mm, width 117 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This albumen print, titled "Portret van Willem III, koning der Nederlanden," comes to us from an anonymous photographer working sometime between 1850 and 1912. What strikes you first? Editor: The overwhelming sense of power—it's a study in royal display. The fabrics alone seem to be speaking of luxury and control. I wonder about the process of creating the albumen print itself, all the material ingredients. Curator: Absolutely. We should think about how power is materially constructed and reinforced here. The very act of commissioning a portrait was a political one. And we have to consider the rapid advancements in photography at this time. This was a relatively new technology, making portraiture accessible to a broader range of people, challenging the elitism of painted portraits. Editor: Yes, consider the chemistry involved in albumen printing, from the silver nitrate to the egg whites. The process itself creates an indexical trace. It is materially evidencing the subject that's standing in front of it. Each material bears social weight and can be analyzed and deconstructed for its use in service to the image’s broader power dynamic. And don’t forget, printing technologies and materials can easily reinforce cultural hierarchies if there is uneven distribution of them. Curator: It certainly raises questions about access and representation. Willem III is depicted here, after all, draped in ermine and brandishing a sword. Consider what is deemed worthy of representation, especially when photographic processes were often limited. His stance, his attire, his very gaze—it's all orchestrated to project authority and, indeed, reinforce his role within a highly structured, patriarchal society. How many labourers extracted and fabricated the objects on display, to empower this monarch to appear for only a moment? Editor: Right! From the mines providing the minerals for the photographic materials to the garment-makers crafting his clothes and finery, photography conceals a massive amount of labor and the often invisible costs and processes of making it. These elements solidify that portraiture does not occur in a vacuum. It is quite amazing to contemplate all the physical stuff embedded and concealed in this image. Curator: Agreed, understanding the socio-political context, along with understanding the means of its production allows us to deeply interpret this moment. It has broadened the work's meaning and forced a deeper level of analysis than previously anticipated. Editor: Definitely! Bringing in materiality illuminates aspects often overlooked in more conventional formal analysis, giving depth and social dimension to even a seemingly conventional royal portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.