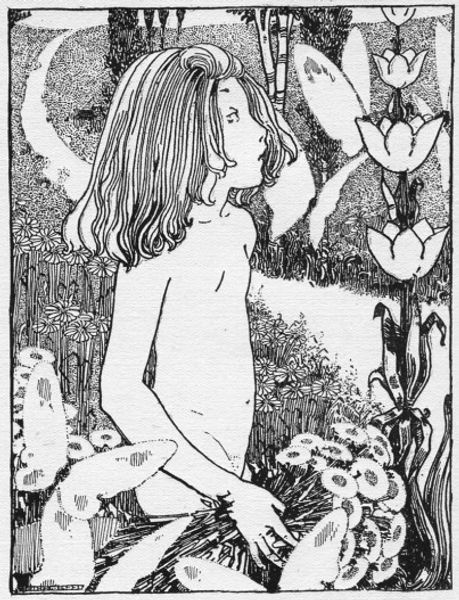

drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

fairy-painting

#

art-nouveau

#

narrative illustration

#

narrative-art

#

comic strip

#

pen illustration

#

fantasy-art

#

paper

#

ink line art

#

ink

#

pen

Copyright: Public domain

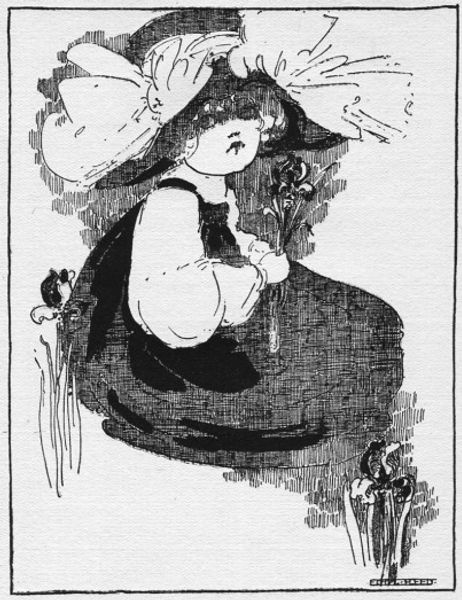

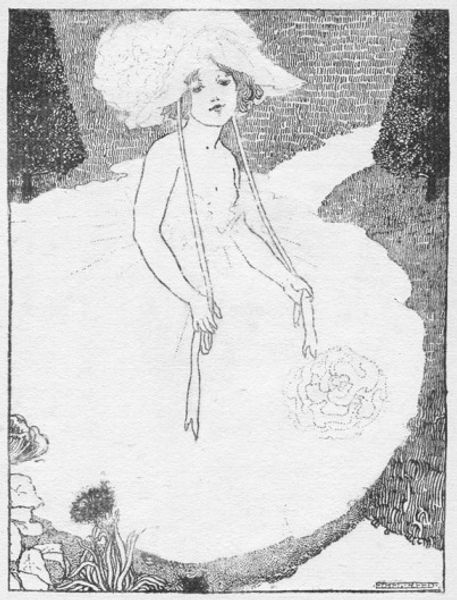

Curator: Welcome. Today, we’re examining Ethel Reed’s "Illustration from In Childhood’s Country (Moulton)", an ink and pen drawing from 1896. Editor: It's incredibly charming. There’s a sort of delicate melancholy in the subject's eyes and in the stark black and white contrasts of the ink. Curator: Yes, Reed’s work during this period certainly engages with themes of sentimental innocence. The composition is structured by contrasting fields of densely worked cross-hatching versus clear expanses of plain white, defining not only the forms but also directing the eye. Editor: Speaking of direction, my eye is immediately drawn to the execution, that meticulous application of ink. Given the time it must have taken to produce the detail, it makes you consider how that process might influence the art. Who was doing the actual labour here? Curator: That's a compelling point. We could consider Reed's own artistic labor, and we can examine her deliberate manipulation of form and line. Her mark-making yields both detailed precision and expressive looseness. Editor: And it invites contemplation on the consumption of such art; the labor and materials embedded become secondary to the sentiment the image delivers, appealing directly to bourgeois sensibilities, but one might wonder who could afford such artwork. Curator: Such inquiries open vital avenues for interpretation. The illustration's success hinges upon an inherent structural ambiguity, prompting subjective interpretations that bridge aesthetic pleasure and societal analysis. The tension lies in the surface—the graceful dance of pen strokes versus the material cost and socio-economic reality of the late 19th century art market. Editor: Exactly, because when we reduce art to its intrinsic value, the means of creating, distributing and engaging is not often thought. This focus, for me, expands meaning rather than diminishing it. Reed's illustration, even with its apparent straightforward subject matter, sparks relevant questions about craft, value and the hands behind the art. Curator: True. And with its composition and meticulousness, there’s an intellectual and sensual sophistication at play here, and, ultimately, the pleasure we derive, in the end, comes from grappling with these sorts of complexities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.