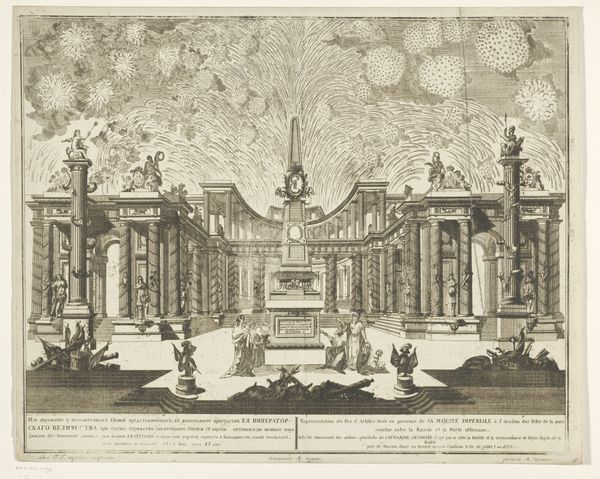

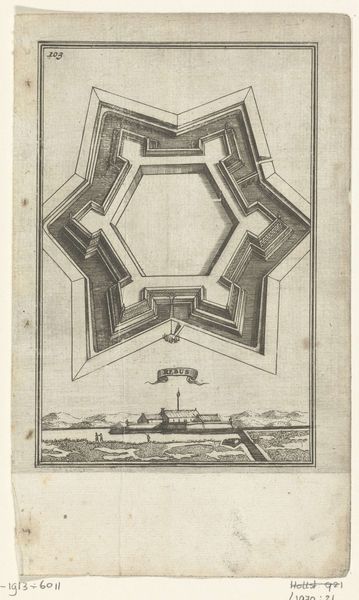

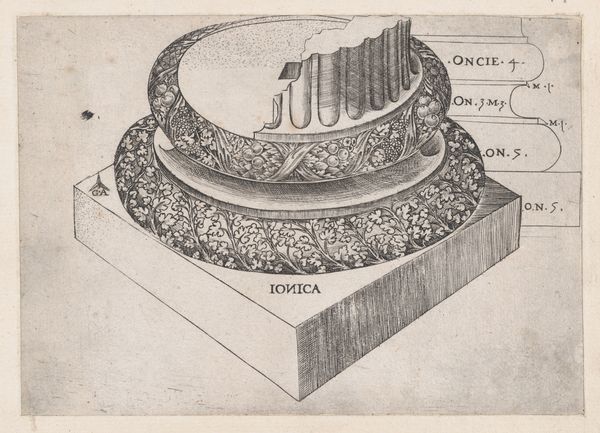

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

pen drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

islamic-art

#

engraving

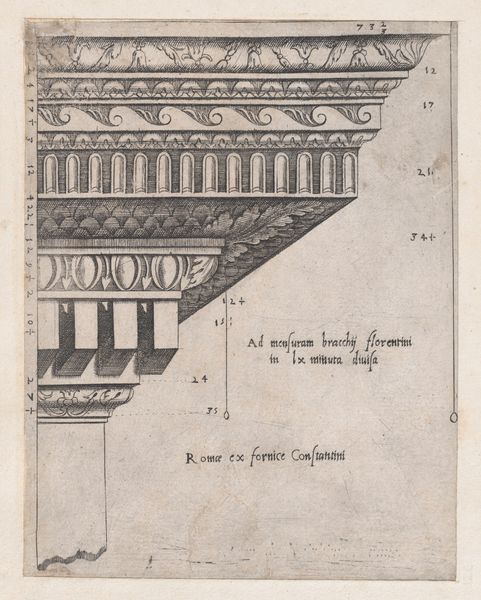

Dimensions: 250 mm (height) x 327 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Let's discuss Melchior Lorck’s etching, "A Sarcophagus in Silivri," created sometime between 1560 and 1564. It's a rather intriguing piece within his broader body of work, capturing a funerary monument with the cityscape receding behind it. Editor: It's arresting, I'll give you that. The severe geometry of the sarcophagus against the feathery etching of the landscape creates an odd tension. The whole composition feels stiff, yet strangely vibrant due to the contrasting textures. Curator: Indeed. What’s particularly fascinating is the artist's engagement with Ottoman culture during his time as an envoy in Constantinople. Lorck's depiction challenges prevailing European Orientalist views. Editor: Challenge, yes, but through a very specific visual language. Notice the ornamentation—the repeated circular motifs, the dense, almost fabric-like texture. It's not a realistic depiction but an interpretation, playing with patterns and lines, an intellectual exercise using visual tools of contrasts. Curator: Absolutely, his approach was less about direct transcription and more about conveying cultural observations. He presents this Ottoman monument not just as an artifact, but in its architectural context within the social and political landscape of the time. The text inscribed along the bottom further hints at the place of the sarcophagus and the patron that commisioned it. Editor: Yet the lack of deep shading flattens the object, removing depth in exchange for an elaborate surface. The image, for me, becomes about this play with surfaces, rather than the actual scene. See how the clouds mimic the rounded forms of the patterns found in the object below. Lorck created visual rhymes. Curator: That's a great point about the lack of shading. We could consider Lorck's intentions through the lens of patronage. His patron probably desired detailed representations suitable for scholarly audiences invested in classical architecture. This work exists because of social demand for a specific mode of visual engagement. Editor: It's a study in contrasts, in a sense. The object itself becomes secondary to how it's translated through line and form. Curator: It all contributes to a nuanced statement on cross-cultural relations and the politics of representation in the 16th century. Editor: It seems we’ve unearthed compelling and diverse aspects, haven't we? Curator: We certainly have. It shows how complex even a seemingly straightforward visual record can be when examined from multiple angles.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.