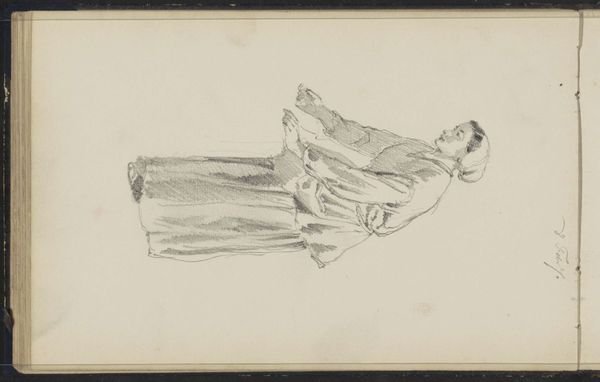

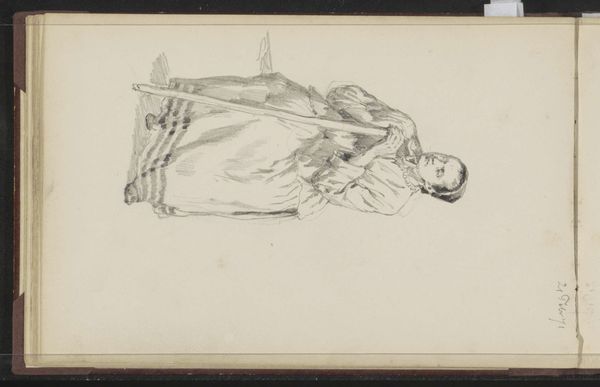

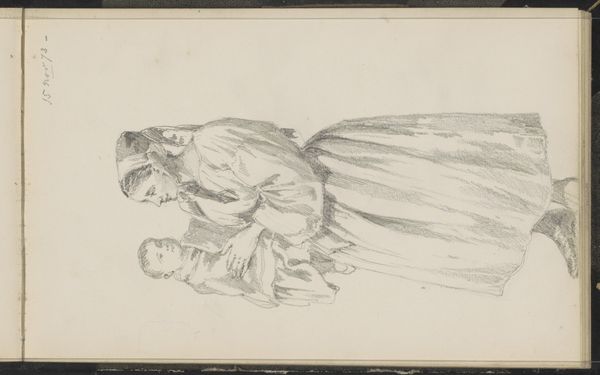

watercolor

#

portrait

#

watercolor

#

genre-painting

#

watercolor

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. We’re looking at “Zittende vrouw met een mes en een aardappel”—“Seated Woman with a Knife and a Potato”—a watercolor housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Its creation is attributed to Cornelis Springer, possibly dating to around 1871 or 1872. Editor: She seems rather… resigned, doesn’t she? There's a weight to the composition despite the lightness of the watercolor. The woman and her task, the muted colors, create a sense of domestic drudgery, a quiet bleakness. Curator: Genre paintings such as this offered glimpses into everyday life for the burgeoning middle class, allowing them to observe, perhaps romanticize, the realities of the working class. The woman here becomes a symbol, perhaps, of virtuous toil. Editor: Symbolism, perhaps, but I am immediately struck by her labor. The material simplicity—a basic meal, a simple knife, her coarse skirt. We are meant to contemplate the woman and also, inevitably, the materials and objects around her. Springer uses the medium of watercolor to highlight the bare facts, unglamorized and immediate. Curator: Indeed. Watercolor’s inherent transparency emphasizes the subject's vulnerability. It’s a far cry from the grand historical paintings favored by the academies. Here, Springer depicts not heroes or gods, but a woman engaged in the humdrum task of food preparation. There’s an intimacy offered here. Editor: Intimacy yes, and let's not overlook the potato, the very stuff of the earth being prepared here and the importance of such subsistence. The potato carries enormous political and cultural baggage and so her working through the tuber carries the load of her position in Dutch society. Curator: Good point, it becomes representative of the broader socio-economic structures at play. The placement of her hand on the potato, almost reverentially, highlights its significance. Editor: Perhaps. All I know is that it provides a glimpse, fleeting as it may be through the eye and hand of the artist, into the labor it took to put food on the table. Even the simple ones. Curator: So, through Springer's rendering of a humble domestic scene, we gain insight into 19th-century Dutch society. Its values, its class structure and daily reality. Editor: Precisely. We get to think not only about the person portrayed, but about what her labor is for and how she undertakes this task by whatever means at her disposal. A powerful combination, no?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.