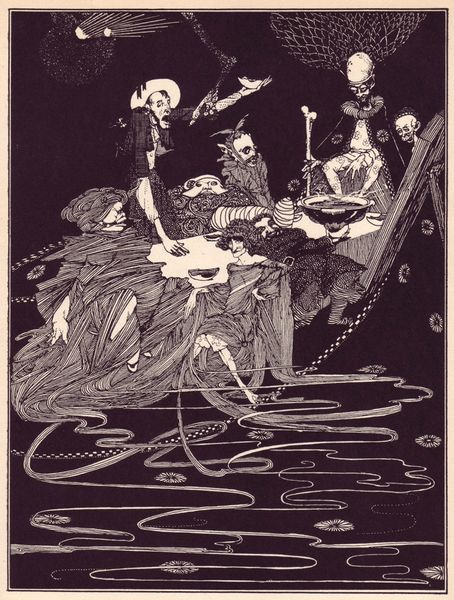

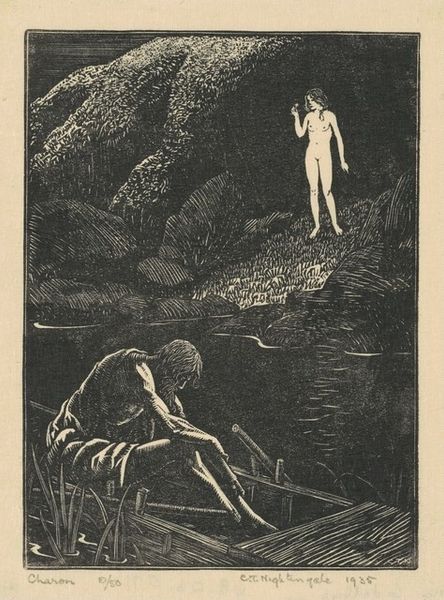

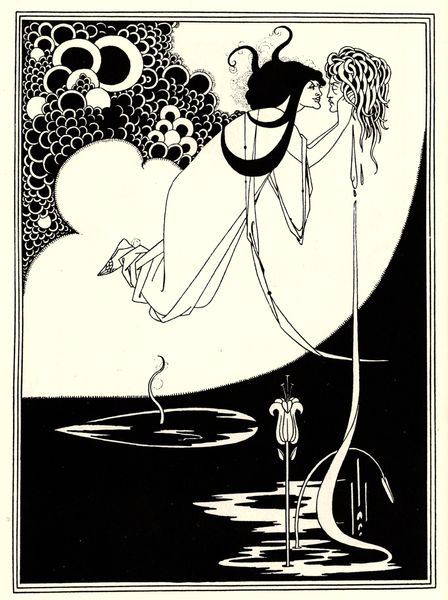

print, ink, woodcut

#

fairy-painting

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pen illustration

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink line art

#

ink

#

linocut print

#

woodcut

#

line

#

symbolism

Copyright: Public domain

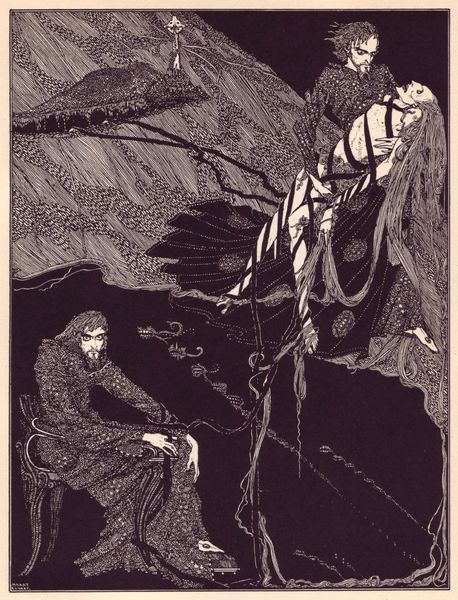

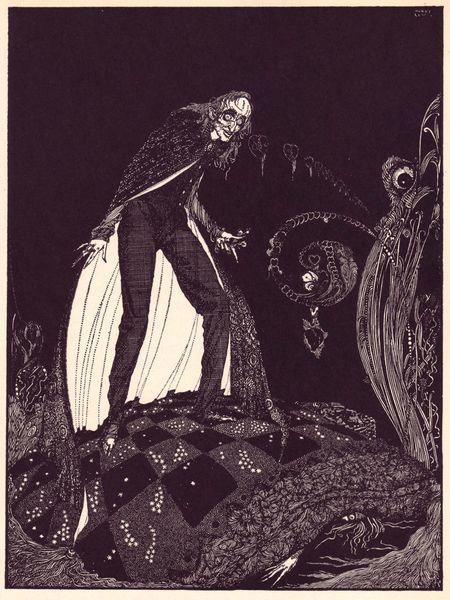

Editor: Here we have Harry Clarke's "The Year's at the Spring" from 1920, rendered in ink, likely a woodcut or linocut print. It’s a striking image with contrasting black and white spaces creating a world inhabited by mythical figures and an ordinary girl. What strikes me is the level of detail achievable through printmaking—what's your perspective on this piece? Curator: This work begs a materialist reading. The very process of woodcut or linocut, a form accessible and reproducible, pushes against the elitism often associated with "high art." Think about the labor involved: the meticulous carving, the conscious removal of material. Does the medium itself democratize the mystical subject matter? How does that interplay affect our reading? Editor: I see what you mean about democratizing art through process. But does the fantastical content detract from a purely materialist viewpoint? It feels very…escapist. Curator: Not necessarily. Consider the social context: 1920, post-war disillusionment. Perhaps the choice of fairy-painting, using a readily available printmaking technique, provides a means of accessible, even mass-produced, escapism *precisely* for a society grappling with material realities. Clarke is offering a fantasy manufactured through very tangible means. Look at the line work; how does that contribute to its reproducibility, its potential consumption? Editor: That's an interesting angle, looking at fantasy as a manufactured product of its time using available processes. It challenges the idea that art is somehow divorced from material reality. Curator: Exactly! It forces us to think about the making – the production, the accessibility, and even the consumption of art within a broader social and economic landscape. Are we, by looking at the ‘how’, more capable of seeing ‘why’? Editor: I suppose we are! Considering the printmaking process and the social context definitely changes how I see the imagery. It connects the mystical with the mundane in a surprising way. Curator: Precisely. Materiality, in the end, impacts meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.