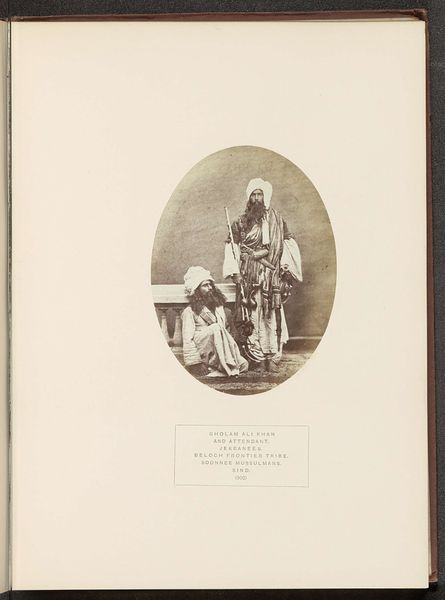

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 147 mm, width 109 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

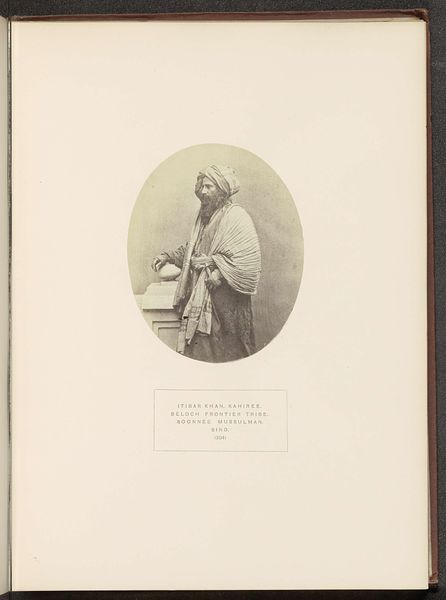

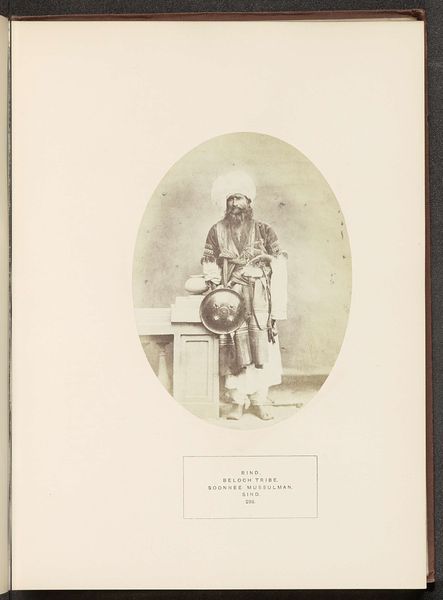

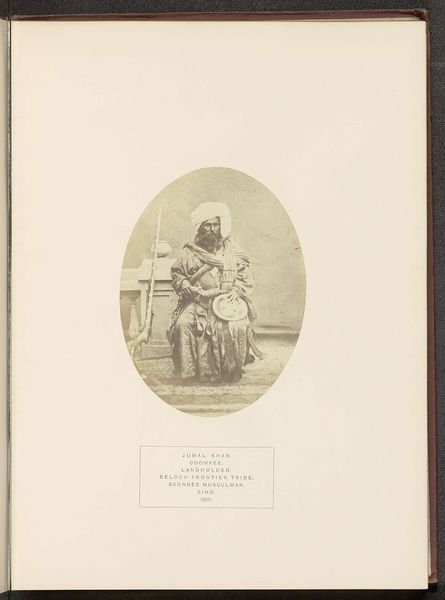

Curator: This albumen print, taken before 1872 by Henry Charles Baskerville Tanner, is titled "Portret van een onbekende Jat man uit Sindh"—that's "Portrait of an Unknown Jat Man from Sindh." My first impression is one of posed formality—slightly stiff, even. Editor: I agree. But look beyond the surface. To me, the symbols are what sing. Notice the striking turban and the decorative sash— these aren’t mere garments; they communicate volumes about social status and religious affiliation within the Jat community of Sindh. Curator: Absolutely. Let’s dig into that. Albumen prints like this were commercially produced, weren't they? Serving a market interested in...exoticizing different cultures? I’m very curious about the division of labour in creating this image – was Tanner calling all the shots or did his sitter have any agency in how he wanted to present himself to the camera? Editor: Precisely! It raises the specter of Orientalism—a Western gaze imposing itself on Eastern subjects. The details—the balustrade, for example—seem artificially constructed, creating an impression of grandeur and order to offset, perhaps, perceived “otherness” that the consumers of these images back home are looking to buy. It really suggests control over presentation, shaping Western perceptions of South Asian identities, something he would then exchange or sell for profit. Curator: And the printing process itself is crucial. Albumen paper— essentially egg white—gave a fine resolution for the time, enabling mass reproduction but its use comes with considerations of access and labour – albumen paper production created entirely new trades! It also gives the photograph a certain aesthetic tone, a warm sepia feel, very characteristic of this period in photography, softening what could be harsh realities with a nostalgic light. Editor: See, I interpret that warmth as almost inviting. The pose and direct gaze still project a commanding presence, I think. But beyond simple power dynamics, there are indications that communicate the culture that this person is very much part of. Perhaps that ornate shawl has deeper roots in regional textiles of Sindh and could communicate trade histories in the region as well as local expertise in clothing design that is very rich! Curator: Indeed, it serves as a potent reminder of the complicated relationships between image-making, colonialism, and consumption. And by focusing on the material and labor that went into producing the print, we hopefully avoid perpetuating the power structures that defined it. Editor: Well, it goes both ways I suppose, it offers both a reflection of Western perception and provides a potential space to see what symbolism transcends that singular point of view. What remains can allow some interpretation that moves closer to those roots. Curator: An unsettling image but important I feel – it challenges us to ask what we’re seeing when we encounter representations of different cultures from the past. Editor: Absolutely, it provokes that urgent curiosity about the meanings woven into clothes, places, and expressions, all those things that link cultures across time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.