engraving

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

rococo

Dimensions: height 146 mm, width 97 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

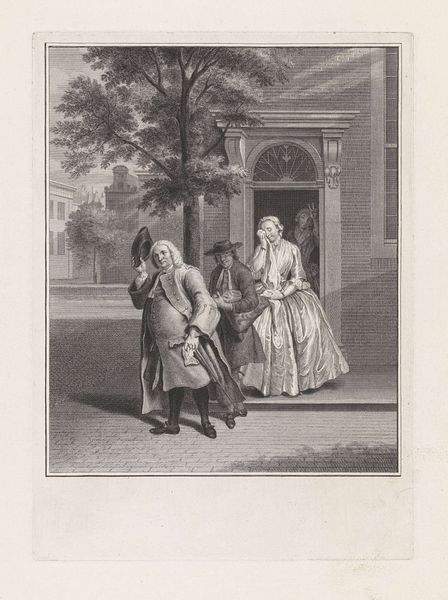

Curator: What strikes me most about this print is the rigidity of the characters compared to the sensuous curves of the formal garden they occupy. Editor: Yes, it's an interesting juxtaposition. The artist, Jan Punt, created this engraving titled, "Man en zijn maîtresses in een tuin" or "Man and his Mistresses in a Garden," in 1758. Look how the hard lines of the building sharply contrast with the sprawling foliage. Curator: It’s all very performative, isn't it? The gentleman, seated and clearly preening under the attention of the women, reminds me of theatrical staging. It is, after all, a scene designed for public consumption, even within its intimate setting. The print undoubtedly speaks to the socio-political norms around courtship, class, and performance of power during that era. The entire scene appears almost like a tableau vivant intended to express status and cultivated taste. Editor: Absolutely, and consider the use of line to define form here. The crispness in the rendering of fabric, foliage, and architectural details underscores the rococo love of elaborate surface detail. The overall organization, though seemingly casual, reveals careful attention to asymmetry. See the delicate web of lines creating soft shadows. Curator: Shadowing in the Rococo period was carefully calculated for mood enhancement and visual intrigue, which absolutely ties in with the broader aristocratic culture in the 18th century—a society invested in outward appearances, fashion, and the construction of the self for an audience. Editor: The details of their garments, the posture, the architectural background… It all speaks volumes, indeed. There's an almost hyper-awareness of style and mannerism, heightened through precise linear detailing. Curator: Indeed, an engraving such as this offered a readily accessible means of circulating such idealized images. In many ways it reinforced the hierarchies of the day by showcasing particular lifestyles while subtly promoting societal aspiration. The print then not merely documents, but actively shapes cultural preferences. Editor: Agreed, the distribution of images like these allows viewers to study the fine balance between line, space, and texture… Perhaps its lasting impact is rooted in the intersection of form and context, offering insights into the way social performance influences aesthetic preferences. Curator: Exactly, for me, this is an image dense with cultural messaging made more accessible through its form and broader circulation in 18th century Dutch society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.