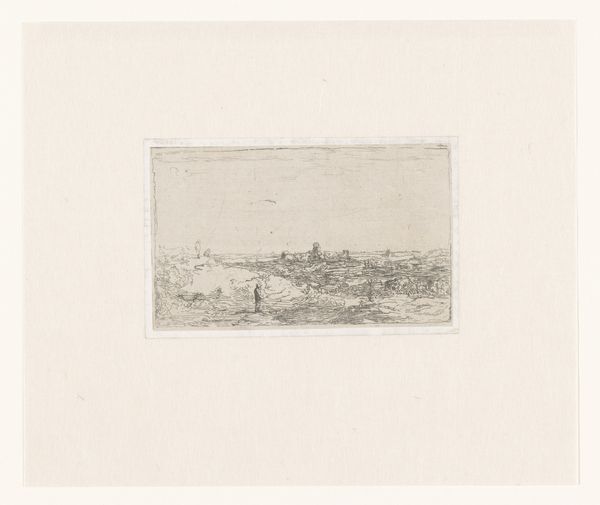

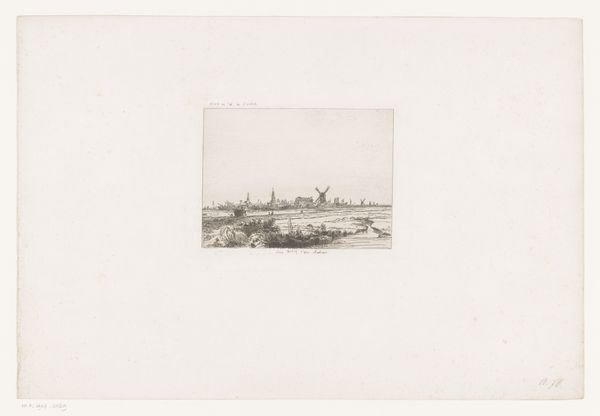

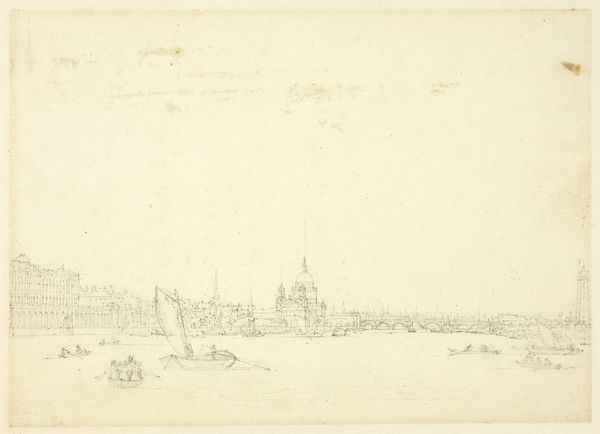

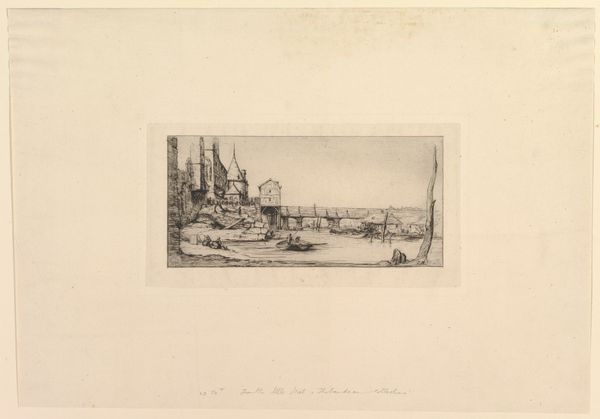

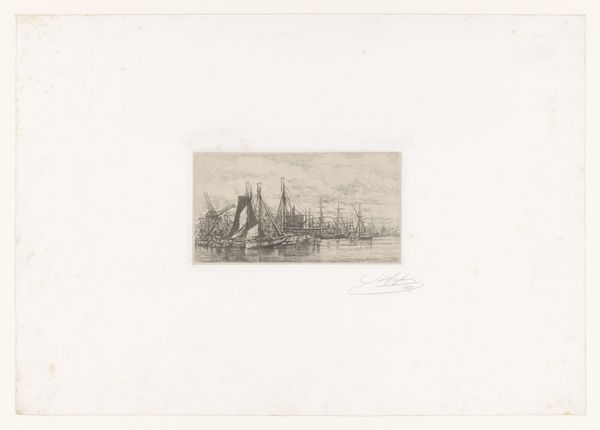

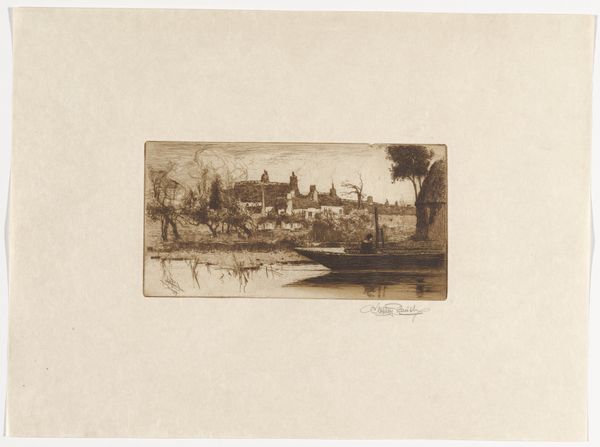

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 119 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Gazing at this etching, "View of Amsterdam," dating from 1863-1868 and rendered by Sir Francis Seymour Haden, one senses… well, almost a ghostly, skeletal quality to the cityscape. What is your take? Editor: There's a stillness, definitely. It's fascinating to see Amsterdam rendered in such delicate lines. It's realism, sure, but a subdued realism that almost hints at the anxieties of urbanization during that period. Did Haden focus on cityscapes a lot? Curator: Not exclusively, but he certainly captured the character of various locales. I'm drawn to the artist’s deftness—that he can evoke a sprawling city with what appears, deceptively, like very little. The way he suggests detail is so much more powerful than spelling it out. Editor: Right. And etchings, prints in general, were such democratized art forms. A readily available depiction of urban space also made these places… consumable. Something to ponder within the rising tensions between capital and the domestic sphere, don’t you think? The availability of an image can alter the reality of its representation. Curator: Precisely! But to turn this towards my slightly more personal interpretation: doesn't this rendition of Amsterdam seem like it’s perpetually existing in twilight? There's this sense of suspended animation, almost as if it is waiting for something. The weight of time presses down on all those tiny spires and rooflines. Editor: Definitely, I understand what you're saying. Also, consider the intended audience: prints such as these may be commissioned or traded to establish political networks, construct shared values of beauty in line with the dominant cultural narrative… The ghostly affect may even reflect shifting imperial interests and power dynamics, with landscapes signaling resources. Curator: Well, I hadn't seen that reading initially, but there's much to consider. As always! Perhaps we've both stumbled upon separate and complementary dimensions of this seemingly small work. Editor: Indeed! And I think by seeing those nuances, this artwork does something so important by enabling the expression of ideas and identities on the rise in the mid-19th century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.