photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

landscape

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 78 mm, width 46 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

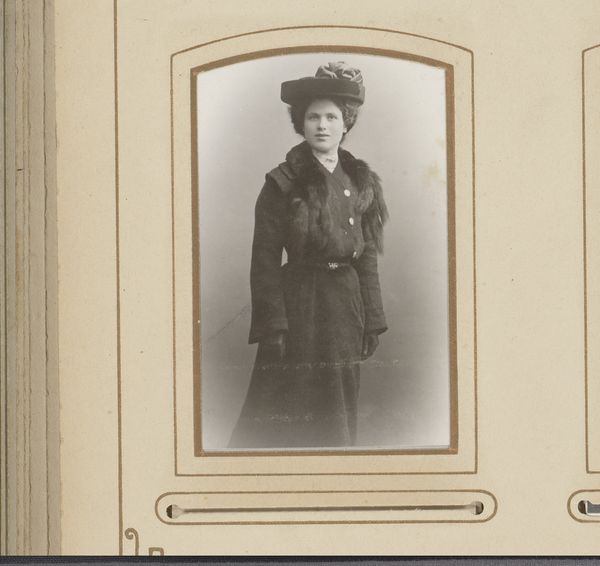

Editor: This is a portrait by P. Steensma titled "Portret van een vrouw met hoed in winterlandschap", created sometime between 1891 and 1931. It appears to be a photograph with watercolor. I'm struck by the contrast between the woman's formal attire and the bleak winter landscape. How do you interpret this work? Curator: It's a fascinating piece, especially when considered through the lens of 19th-century societal expectations for women. Her clothing signifies a certain level of social standing, but placing her in a stark winter landscape seems to subtly undermine that. Do you see any hints of agency or constraint in her posture or expression? Editor: She looks rather stoic, almost detached from the setting. Her gaze doesn't seem to engage with the viewer either. It makes me wonder about her story. Curator: Exactly! And what stories weren't being told? Portraiture of this era often served to reinforce societal norms, yet photography, even with later watercoloring, could offer a glimmer of reality, or resistance. Consider how the male gaze often dominated artistic depictions of women; does this photograph challenge or perpetuate that? Editor: That's a great question. I guess I hadn’t thought about the male gaze here, but it feels like the photographer, perhaps intentionally, invites a sense of introspection rather than objectification. Curator: Precisely. And what about the implications of a female photographer, especially considering that access to artistic institutions was difficult at the time? What would change the analysis if it had been the photographer's self portrait, maybe taken to suggest to be an advertisement for Steensma´s business? Editor: It certainly opens up different possibilities! It challenges the narrative by inserting the female gaze. I’ve learned a lot about the importance of considering the photographer's role and how context changes everything. Curator: And that's precisely what makes art history so rewarding: the ability to weave together different perspectives to create richer, more nuanced readings of visual culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.