drawing, ink, pen

#

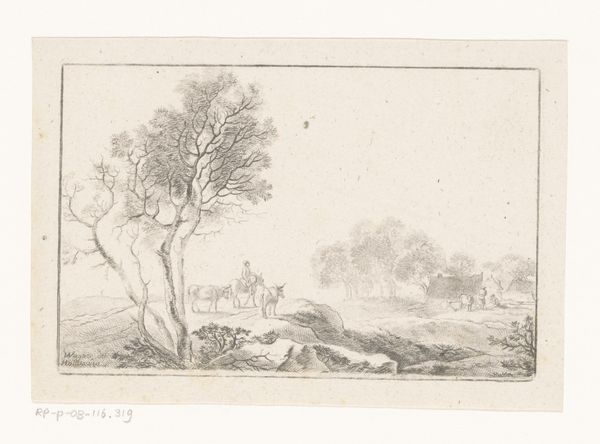

drawing

#

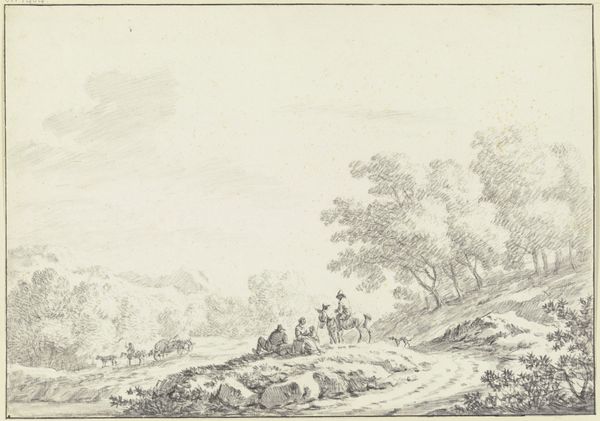

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

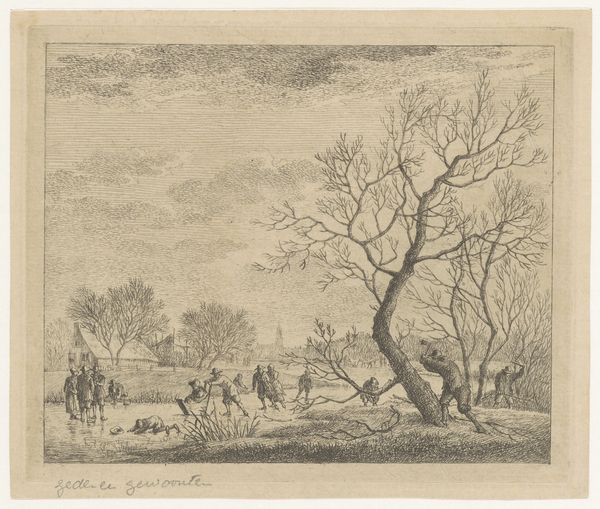

etching

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

botanical drawing

#

pen

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 310 mm, width 445 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This evocative landscape scene is "Vrouw met kind en man met ezel in landschap," or "Woman with Child and Man with Donkey in a Landscape," by Egbert van Drielst. It was created sometime between 1755 and 1818. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's wonderfully atmospheric. There’s a certain wistfulness to it, a sense of timeless rural life sketched with remarkable precision. The subdued palette enhances that feeling, almost as if looking at a faded memory. Curator: Drielst's works are significant because they depict an idealized vision of rural life during a time of great socio-political change. We're talking the Dutch Patriot revolution and the Napoleonic era. There's a deliberate focus on seemingly unburdened families and their animal companions in idyllic settings. Think about the power structures, and how a scene like this contrasts against other possible representations during a moment in history where economic instability began fracturing familial roles. Editor: I agree, placing it within the context of rapid societal change reveals a potential longing for a perceived simpler past. Looking closely, I notice the figures seem less like individual portraits and more like symbolic representations of a traditional social order. But is it authentic nostalgia, or a politically motivated projection? Curator: Perhaps a bit of both? We can trace its influence to similar Romantic works seeking refuge in nature from rapid industrialization. Drielst's strategic compositions create a powerful message about gender roles and the perceived resilience of rural families. Who, after all, feels more burden by the times than the mother pictured here, holding her child? The presence of a church suggests established institutions and hierarchies are still significant as well. Editor: Precisely! The artist makes choices, after all. By using what appear to be deliberately traditional motifs, it positions those social roles as cornerstones in the viewer's collective imagination. How does it reflect—or perhaps dictate—expectations of society as a whole? Curator: I'd say it leaves us considering who benefits from an artwork portraying unwavering norms and social standards as idealized virtue—an artwork still being exhibited for consumption to this day. Editor: Indeed. Looking at it with fresh eyes, the apparent serenity of the drawing suddenly asks compelling questions of the modern audience about who it shows, who it excludes, and why.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.