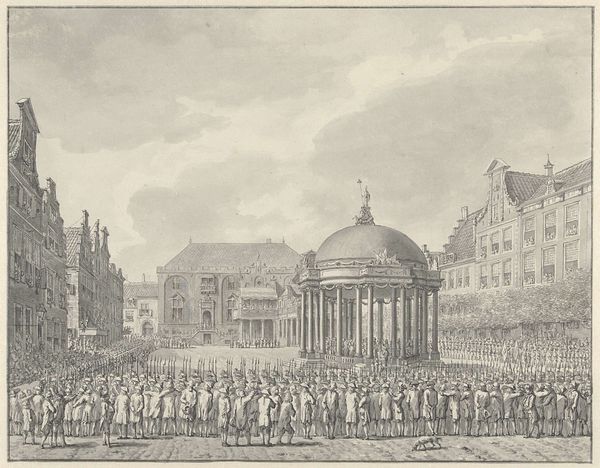

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

line

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 369 mm, width 475 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Bastiaen Stopendael’s "Entry of King William III into The Hague, 1691," an engraving printed in that same year. It’s a bustling cityscape with a clear propagandistic intent. What elements do you consider most significant here? Curator: For me, the key lies in understanding the socio-economic circumstances of printmaking at that time. The proliferation of prints like this demonstrates an evolving media landscape. Engravings facilitated mass consumption of imagery, essentially democratizing access to visuals of power. Editor: So you're focusing less on the "art" and more on the production aspect? Curator: Precisely! Consider the labour involved in creating the plate, the paper used, and the distribution networks that allowed this image to circulate. Who was the target audience? What social and political needs did it serve? Was it widely circulated or exclusively aimed at the elite? These aspects of materiality help reveal the cultural mechanics behind it. How accessible would you say this type of artwork was to all the members of society? Editor: I guess it depends on literacy levels, as there's quite a bit of text. Perhaps it reached a more bourgeois audience rather than the absolute poor. Curator: Exactly. The print functions as both image and text, and its significance hinges on its place within 17th-century Dutch society and its production systems. By investigating these angles, we reveal how it worked to perpetuate certain social hierarchies and political agendas. Editor: That's fascinating! I never considered the material aspects of propaganda so thoroughly. Thanks to your insights, it highlights the power of mass production and how those details changed how the image had meaning for people in that period.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.