Copyright: Public domain

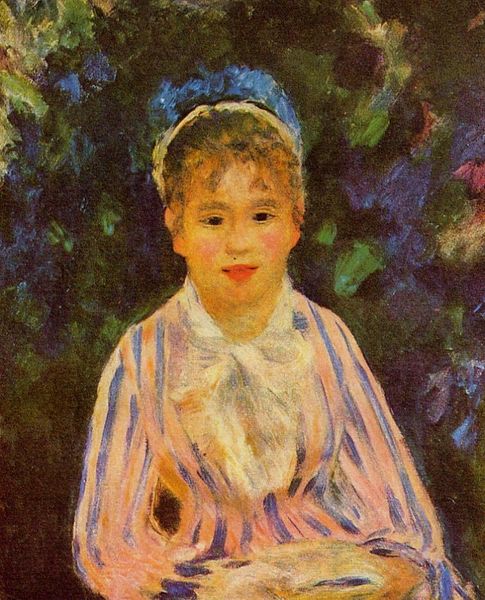

Curator: We're looking at Pierre-Auguste Renoir's "Dame en toilette de Ville," from 1875. Editor: It strikes me as… unfinished, raw. You can almost smell the linseed oil and feel the artist's rapid brushstrokes on the canvas. Look at that textured surface! Curator: Precisely. Renoir, and the Impressionists in general, were concerned with capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light, which he certainly demonstrates through these deliberate, broken strokes. What do you see symbolically? Editor: It's all in the rendering, which reveals so much about how these images come to signify prestige. How quickly it's done! Not a laborious piece but a dash, a gesture toward a type rather than the production of an 'exact' likeness as with more traditional commissions. The very handling of the paint feels bourgeois. Curator: Agreed. Consider the sitter's gaze. It suggests introspection, a subtle melancholy perhaps, yet there is a decorative impulse at play too. Look at the placement of the ribbons and feathers around her face, each strategically placed to emphasize her fashionable status and conventional beauty. It invites a reading of beauty as itself a constructed symbol, almost a form of armor. Editor: A constructed symbol indeed. Consider how paintings like these served as calling cards, establishing the status and access the sitter was afforded, given her wealth and the cultural capital such finery suggested. Renoir himself became a part of that cycle of image production and wealth. Curator: Exactly, this becomes apparent when examining the history of similar portraits and the changing role of women in Parisian society at this time. These symbols speak to aspirations of belonging and status. Editor: The material evidence—the layering, the visible brushstrokes—points to that dynamic interplay between artistry, industry, and consumption that was burgeoning at this point. Curator: An apt description; a nexus where social values, aesthetic ideals, and material practices converge. Editor: Ultimately it leaves us with more to ponder than a static portrait; rather a dynamic slice of 19th-century life laid bare.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.