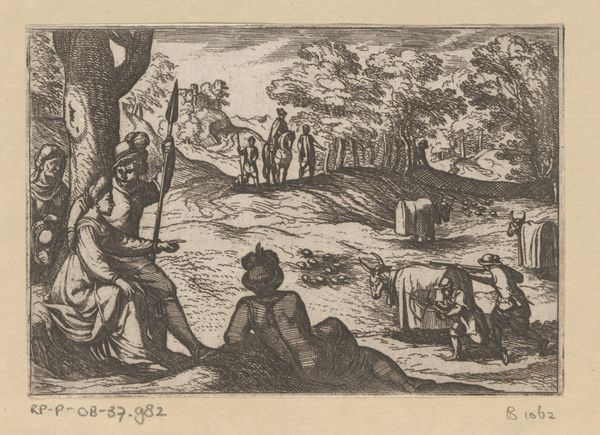

print, etching

#

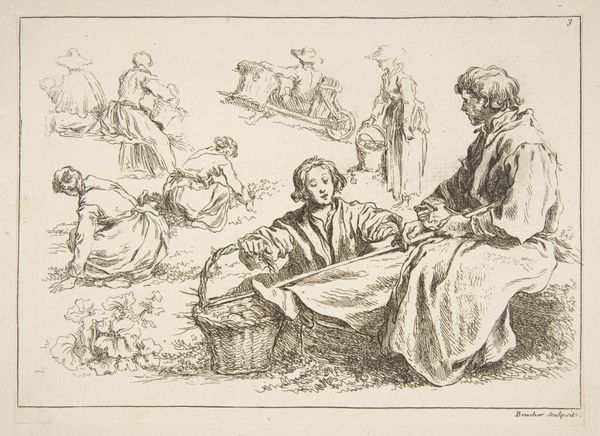

pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

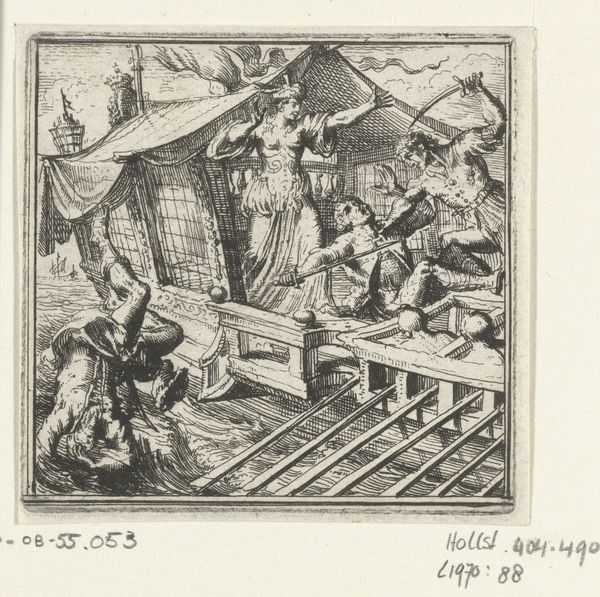

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

group-portraits

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

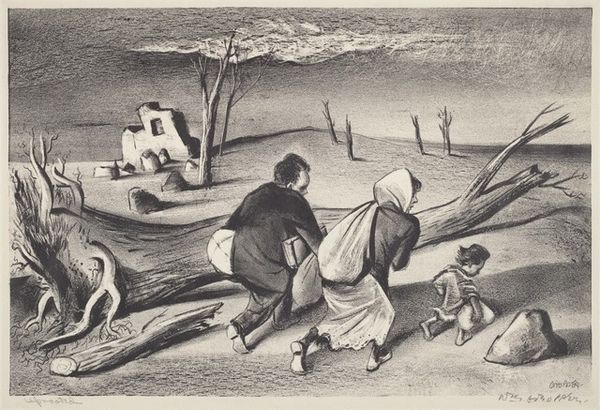

realism

Dimensions: plate: 101 x 125 mm sheet: 129 x 191 mm

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

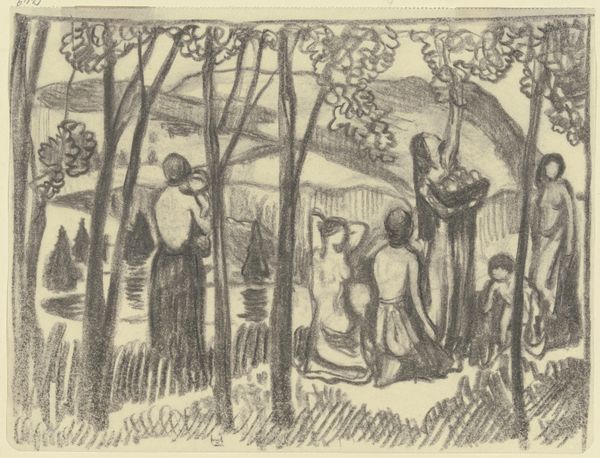

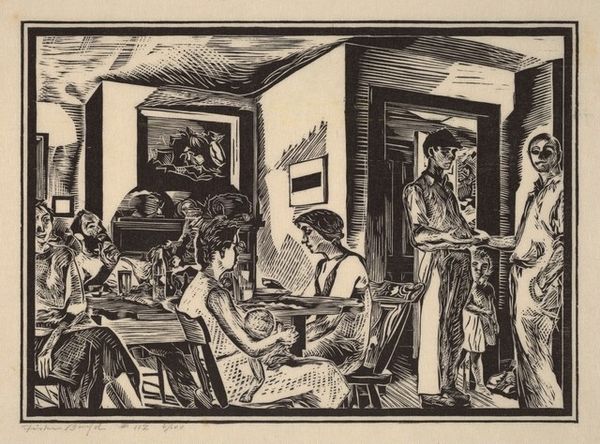

Curator: This etching, dating from around 1926, is titled "Picnic" and was created by Beulah Stevenson. It’s rendered in a monochrome palette, characteristic of prints from this era. Editor: My immediate impression is of intimacy despite the bustling scene. It feels very personal, almost like a candid snapshot lifted from a family album, despite the scratchy pen strokes, or maybe because of them. Curator: That intimacy is interesting considering the context. Etchings, even those depicting leisure, often circulated within broader social networks, conveying cultural values around leisure and class. Do you pick up on any particular symbols that resonate? Editor: Oh, definitely. The very act of a picnic speaks to a deliberate engagement with nature and a sense of community. There's the positioning of the figures in a circular arrangement. The bottle being poured, shared food and drink…it all echoes classic depictions of communal feasting and ritual. Curator: Good point. There's a strong genre painting element here too. These depictions of everyday life contributed to defining what was considered normal or desirable at the time. I see it as playing into the idea of the modern family unit. The framing with the trees feels very stage-like. Editor: I’d argue that there is a suggestion of a more profound meaning beneath its familiar depiction. Food often stands for more than mere sustenance; in this case it embodies connection, kinship, but also mortality, as something consumed, and, perhaps eventually forgotten. Curator: Perhaps. But the imagery in itself doesn't overtly signify those layers. Stevenson could just be recording a commonplace event with the values reflecting society at the time. I think that without written accounts it would be challenging to claim Stevenson set out to do this beyond face value. Editor: I disagree; that doesn't mean we shouldn't try to unlock any hidden meanings. Even common social activities can act as expressions or even celebrations of beliefs. By bringing them to our attention, Stevenson might suggest a more thoughtful or reflective dimension to an experience, transforming its cultural role from banal into powerful. Curator: That’s certainly something to consider as we think about how artistic imagery interacts with the audience through changing historical tides. It makes me think about how perceptions will change for contemporary observers viewing this pastoral setting almost one hundred years after the etching’s conception. Editor: Indeed, these symbolic interpretations, I hope, provide a link through the centuries, enriching not only the artwork itself but its context within the museum as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.