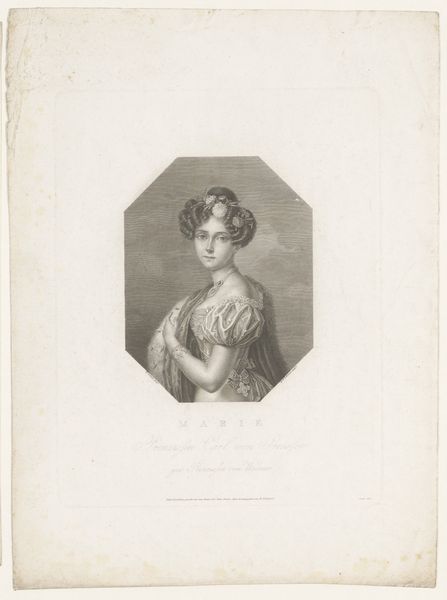

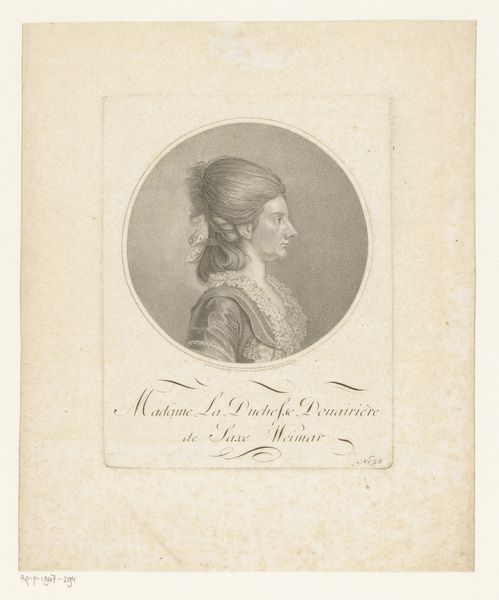

print, engraving

portrait

pencil drawn

neoclacissism

light pencil work

pencil sketch

old engraving style

pencil work

history-painting

engraving

monochrome

Dimensions: height 230 mm, width 152 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: It strikes me as immediately cool, composed…almost melancholic. Like a pressed flower in an old book. Editor: I can see that. Here we have a monochrome print from around 1810, titled "Portret van Marie Louise van Oostenrijk, keizerin der Fransen," which translates to "Portrait of Marie Louise of Austria, Empress of the French.” It is unsigned, credited to D. Schmidt, made via engraving. Marie Louise was, of course, Napoleon's second wife. Curator: Right, the arranged marriage for political reasons! Knowing that just adds a whole other layer of constraint, doesn’t it? She looks young, burdened somehow, despite the finery. It's all so formal—the ruffled collar, the intricate hairstyle. Editor: Indeed. The piece adheres to the Neoclassical style. This involved clear lines, a sense of order, and a focus on historical or elevated subjects, and you certainly feel a pressure to represent her with the grandeur fitting of her position, even while being intimate in format as it is on paper. How does it function, do you think, as a depiction of Imperial power versus a depiction of personhood? Curator: That’s the push and pull, isn't it? The delicacy of the engraving—that "old engraving style," if you like—lends it an air of vulnerability, at odds with the imperial context. The light pencil work almost reveals her fragility. But maybe I'm projecting a bit. Is the frailty present, or am I filling it in? Editor: Perhaps the point is that the framework of empire demands it—Marie Louise exists to play a role; her individuality almost immaterial next to that, even in portrait. A sense of impending change—and there was quite a bit of change that she would preside over the demise of, ultimately! Curator: So beautifully put. Thinking about her place in history really heightens the portrait's sense of quiet sorrow, the tight constricting lines—it truly feels like a small window into the human cost of history, a history dictated by empires and monarchs. Editor: Agreed. I’ll carry with me an acknowledgment of both what the art shows—and what we, looking back, now know. A testament to human drama hidden beneath stiff portraits and formal presentations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.