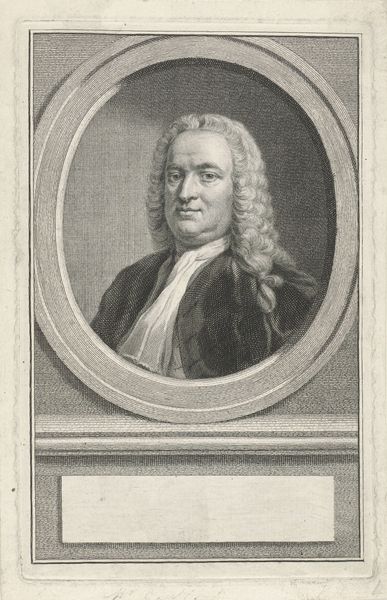

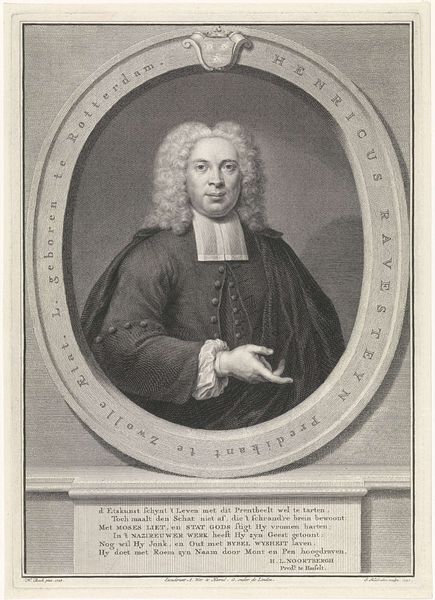

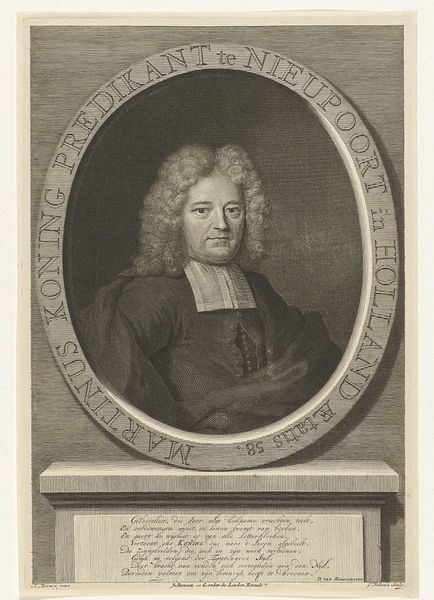

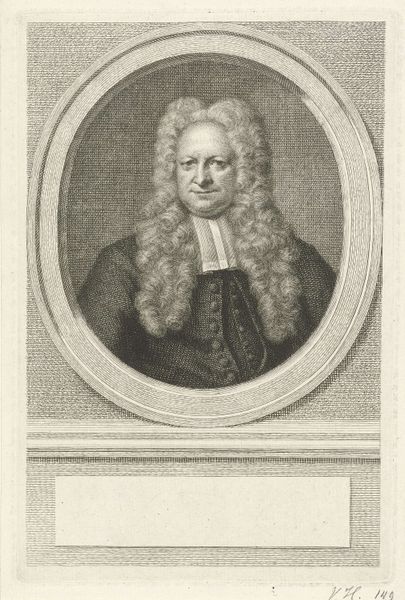

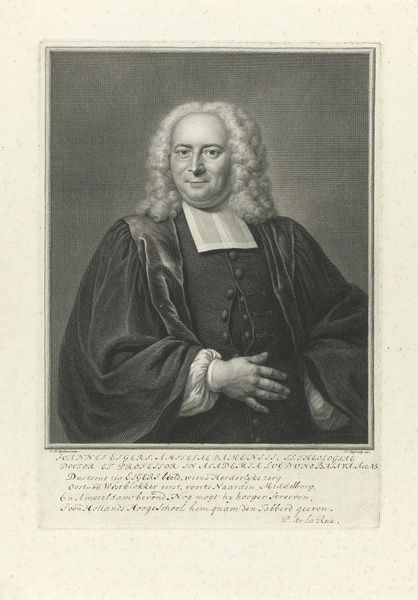

print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

paper

#

line

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 299 mm, width 196 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

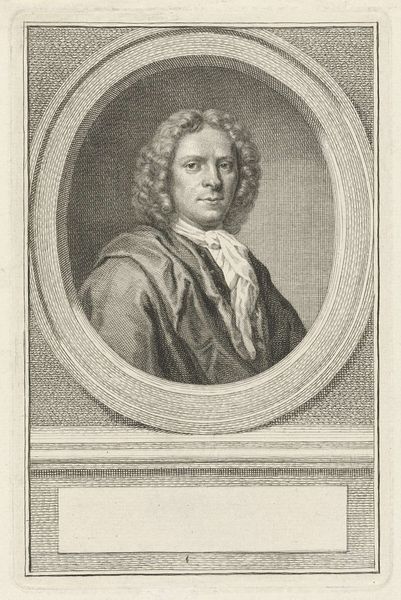

Curator: Good morning. Here we have a fine engraving, "Portret van Johannes Oosterdijk Schacht," created in 1753 by Pieter Tanjé, currently residing in the Rijksmuseum collection. It’s rendered in delicate lines on paper. Editor: It’s quite striking. The detail in the face and the wig is extraordinary, a stark rendering of an era caught in monochrome. What do you make of the textural details in this portrait? Curator: Tanjé’s command over the burin is remarkable, evidenced by the intricate web of lines that articulate Schacht’s face and attire. Note the variance in stroke weight to achieve a tonal depth. This control underscores the values in representing the status and the perceived gravitas of the sitter. Editor: Yes, but also consider the social impact. The creation of engravings like this would have required specific artisanal skills and workshops. Tanjé and his team were working, consuming resources, and participating in an early form of image dissemination, spreading the visage of the elite through prints. The paper itself—its provenance and processing—adds layers to the story of this portrait. Curator: An excellent point about its physical creation and circulation. From a structural standpoint, however, the ornate frame depicted within the print mirrors and amplifies the portrait's purpose. It’s not merely an image but a symbolic presentation. The subject’s gaze and the almost theatrical lighting enhance the intended hierarchy. Editor: I agree the composition leans into those cues of class, but the engraving as an object challenges pure hierarchy. Multiple copies would have been made, traveling to different contexts and hands, interacting with diverse lives and spaces far removed from the elite sphere represented within the frame. Curator: Certainly, the medium allowed for dissemination, which does affect reception. Yet the rigorous precision of the line work, its commitment to Renaissance ideals of mimetic representation… these elevate the portrait to more than just a functional object. It’s a careful negotiation of the sitter’s place within society. Editor: A negotiation using laborious means, requiring considerable human skill to carve those precise lines into metal plates, using tools forged and refined. It speaks volumes about 18th-century industry supporting portraiture—the human labor making “immortality” reproducible. Curator: Seeing through that lens broadens our understanding immensely. It is more than meets the eye, then. Editor: Indeed, by recognizing both the material and its structural elements, we uncover a more vivid story.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.