Four small boys and a goat (copy in reverse) 1650 - 1750

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 5 1/16 × 7 15/16 in. (12.9 × 20.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

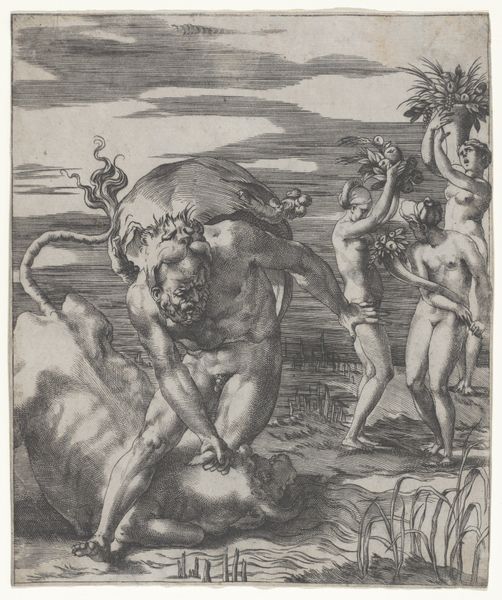

Curator: This engraving, dating from between 1650 and 1750, is called “Four Small Boys and a Goat (copy in reverse)” and is attributed to Wenceslaus Hollar. It’s currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My immediate thought is… chaotic. The composition is lively, verging on unruly, with these plump children seemingly struggling with this equally unruly-looking goat. There's a real sense of movement. Curator: Absolutely. The goat, likely referencing the astrological sign Capricorn, takes on a much older pagan symbolism, associated with virility, abundance and, in some traditions, the god Pan. Children astride or grappling with animals, often goats or bulls, represent mankind taming base instincts or embracing natural forces. Editor: So you're saying that, these figures – far from being simple cherubic children playing with an animal – might embody the struggle for control or harmony with the natural world and raw urges. Does the 'reverse copy' add to or subtract from this symbolic weight? Is something lost in translation? Curator: The fact that it is a reverse copy raises fascinating questions about the transmission and interpretation of symbols. The reversed image might unconsciously signal a deviation, a subtly altered meaning from the original intention or archetype, that challenges established ways of viewing such iconography. This begs the question whether these were even intended to act as archetypes in their original form. Editor: This reminds me how power has historically been expressed through visual representation. This struggle—even the children who seemingly conquer the goat—mirrors colonial narratives where "civilized" forces sought to dominate the "untamed" lands and their populations. It feels reminiscent of allegories of colonial and ecological domination. Curator: A persuasive argument! From my vantage, considering shifting social views of innocence in the Baroque era, where childhood itself was only just emerging as a distinct category from adulthood, perhaps such art also highlights the fleeting nature of control itself and underscores how fragile these imposed structures might prove in reality. Editor: An idea indeed rich in depth! Examining these figures—both human and animal—really encourages us to consider intersections between cultural symbolism and broader conversations about power, control, and our ongoing relationship with the natural environment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.