drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 245 mm, width 188 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

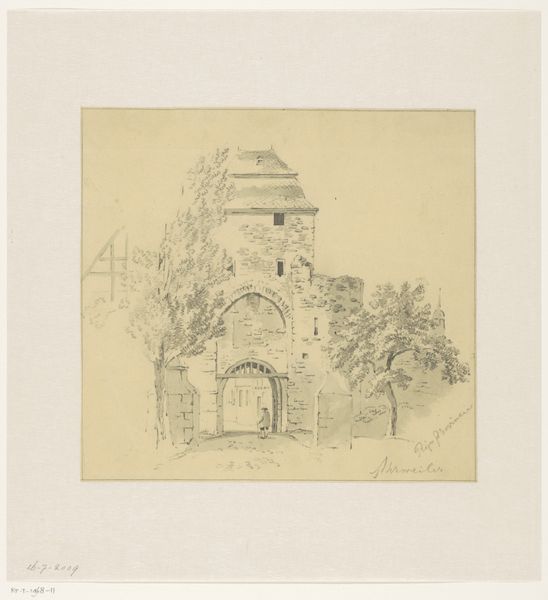

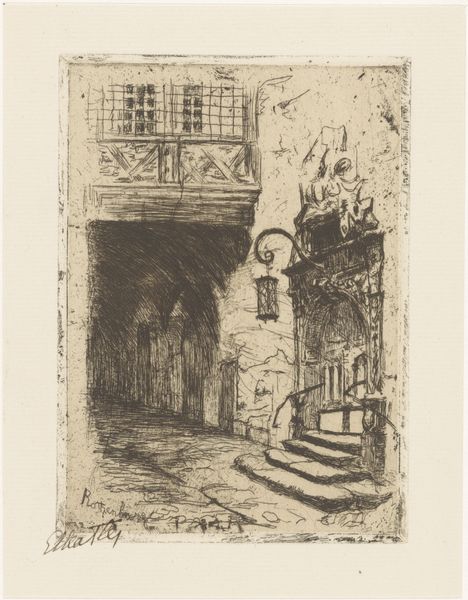

Curator: Here we have a 19th-century work by Ernst Zipperer, "Gezicht op een poort met een paard-en-wagen," a drawing and print created with ink on paper, using an engraving technique. Editor: It’s beautiful, almost dreamlike. The stark contrasts of light and shadow immediately create a sense of profound stillness and history, though perhaps with a looming unease. Curator: It's interesting that you say that. The cityscape, framed by a prominent archway, features a horse-drawn carriage receding into the distance, almost as though history itself is receding. We need to consider what historical realities were reflected in depicting urban environments. The 19th century witnessed rapid industrialization and urbanization. How did such prints influence the public perception of these changes? Editor: Absolutely. It's difficult not to think about class structures when looking at an image like this. Who benefits from the horse-drawn carriage and who is excluded from that privilege? The archway could be seen not just as architectural but as a metaphor for socio-economic barriers. I can’t help but wonder about access to this world shown. Whose narrative are we seeing and who's omitted? Curator: That’s an insightful question. The artwork serves as a fascinating historical document, capturing a specific moment in time while also raising complex questions about power, representation, and the ever-evolving urban landscape. This artwork's public role may also offer nostalgic undertones by highlighting how modernization began changing familiar city landscapes, sometimes not for the better. Editor: Seeing through your lens enriches my understanding of its value beyond mere aesthetics, too. Thinking about who had access to view such artworks further highlights those socio-political realities during the 19th Century. Curator: Agreed. Appreciating art in such a holistic, intersectional manner enriches our shared understanding of this era, urging more reflective public conversations about what shaped urban societies as we see them today. Editor: Indeed, such engagement with both artistic interpretation and social contexts allows for more nuanced perceptions of the work and its place in both art history and also, crucially, public discourse.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.