print, photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

sculpture

#

memorial

#

landscape

#

photography

#

desaturated colour

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

italian-renaissance

#

architecture

#

statue

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 191 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

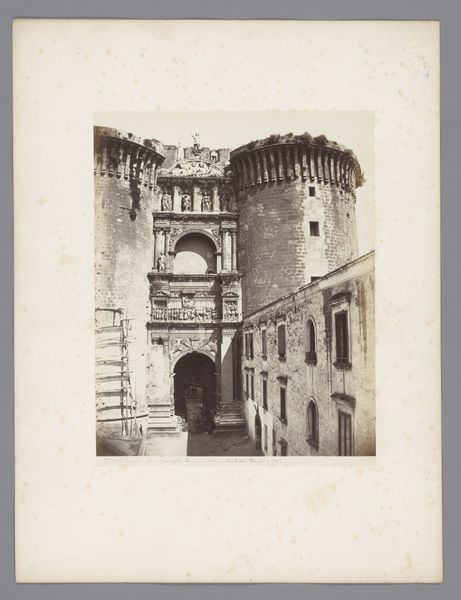

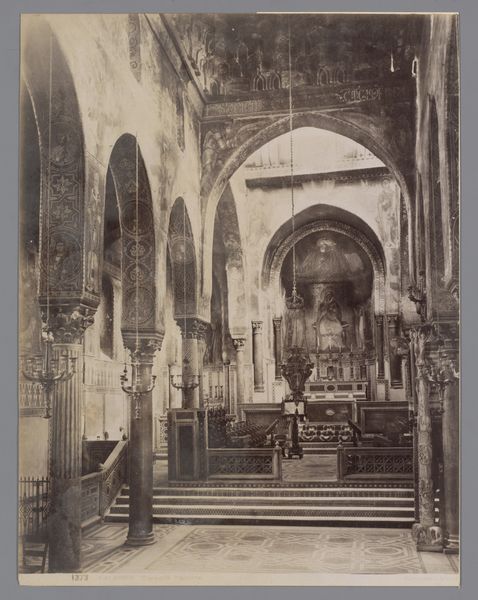

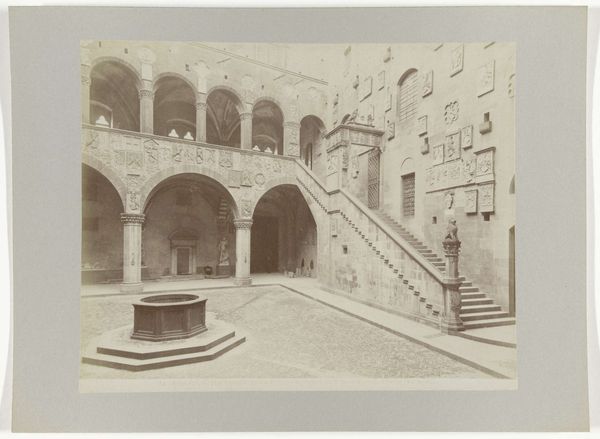

Editor: So, here we have a photograph from the late 19th century, taken by Fratelli Alinari. It's a view of the staircase at the Museo Nazionale in Florence, captured in a gelatin-silver print. What strikes me is the overwhelming detail in the architecture and stonework – almost feels like every surface has been deliberately worked. What do you make of it? Curator: The materiality is definitely key here. Think about the labor involved in extracting, transporting, and carving that stone. Each detail speaks to the skill of the artisans, but also to the social and economic structures that enabled such massive undertakings. The Renaissance wasn’t just about artistic genius, it was about capital, access to resources, and systems of patronage, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: That makes sense. You're shifting the focus from the artistic vision to the physical making of the museum. Did the photographic process also influence the visual language in some way? Curator: Absolutely! Photography in this period was about documentation but also about claiming ownership and control over these cultural objects. Look at the lighting; it accentuates the texture of the stone. How does that relate to, perhaps, the control over labor and materials? Consider also how the industrial revolution was transforming society – how was labor organised then? Editor: It sounds like the photograph, for you, isn’t just capturing the beauty of the Renaissance; it's documenting a complex web of production and power. Curator: Precisely. The building becomes a physical record of labour – we can start to think about how such enterprises affect those involved on a socio-economical level. So what can we see about that from here? Editor: Thinking about it that way, I now appreciate the photograph much more for its ability to bring visibility to otherwise unseen processes. Curator: Indeed. The image then becomes a site of inquiry, a space where art history engages with labor history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.